6. Doubters

But even before Germany had surrendered, several of those involved with the Manhattan Project, convinced that the great evil of Naziism had been subdued and the danger of a German atomic bomb had passed, argued that the bomb ought not to be used against Japan. In other words, the target of the bomb should be understood as having been defeated, and the bomb’s aiming point not merely shifted to another nation. It must be said that there was not much sympathy for the Japanese themselves—while the Jewish refugee scientists especially regarded them as less malignant than the Nazis, most also remembered Pearl Harbor, read the news of the ferocious island-hopping campaign, and shared the view, held by most white Americans, that the Japanese were not quite human. Instead, the scientists’ major concern was that combat use of the bomb against Japan would set a bad precedent for the rest of the world and would in particular antagonize the Soviet Union, which would feel threatened by the US attack and would consider it necessary to race ahead with a bomb-building project of its own.27

Niels Bohr was an early advocate of informing the Soviet Union about the bomb project, thereby hastening a return to the republic of science and an ‘open world’ of information exchange. Bohr had traveled to Los Alamos in 1944 and had there advocated, in his elliptical way of speaking, the use of the bomb as a symbol of international hope and an opportunity for international cooperation. He did not, apparently, recommend specifically against using the bomb in Japan, but he stressed the singular evil of Hitler and told Oppenheimer confidently that ‘nothing like’ Naziism ‘would ever happen again’. Leo Szilard went further. Szilard had energetically promoted the bomb, and to him belongs a good deal of credit for harassing US authorities into taking the project seriously early in the European war. Gradually, however, Szilard’s gifts as a scientist became less relevant to the task of crafting the bomb itself. In early 1945, as Germany’s defeat loomed, Szilard decided to talk to Roosevelt about the urgent need for postwar control of nuclear weapons. He solicited a letter of introduction from Albert Einstein, gained permission to take his cause to the President from Arthur Compton, and secured, through Eleanor Roosevelt, an appointment at the White House—for 8 May 1945. When FDR died on 12 April, Szilard managed to reschedule with Truman. He got as far as the office of Truman’s appointment secretary Matthew Connelly, who assured Szilard that his boss took him seriously, then shunted him off to South Carolina for a meeting with James Byrnes, the man who was soon to be secretary of state, though Szilard did not know this.28

Szilard took Harold Urey and University of Chicago dean Walter Bartky along for support; the men arrived by train in Spartanburg on 28 May. Szilard presented Byrnes with Einstein’s letter and read a memo, which suggested that dropping a bomb on Japan would probably move the Soviets more quickly toward making a bomb of their own. Byrnes remonstrated. Groves, he said, had told him that there was no uranium in the Soviet Union. Having spent $2 billion on the bomb, not to use it against Japan would ultimately dismay Congress and make it difficult to get funding for nuclear research in the future. And, Byrnes implied, the Soviets, who seemed to him up to no good in the East European nations they had liberated from Germany, might be easier to deal with if the United States dropped an atomic bomb. At this point, Szilard remembered, ‘I began to doubt that there was any way for me to communicate with Byrnes in this matter.’ Szilard and his colleagues took their leave in a fog of depression.29

Szilard returned to the Met Lab and discovered he had, as he often had, generated controversy. The Army was angry that Szilard had been permitted to get to Connelly and especially Byrnes. Bartky was reprimanded by Groves and scolded for giving Szilard’s memo to Byrnes; Groves considered Szilard ‘an opportunist’ with ‘no moral standards of any kind’. Compton loyally backed his scientists, and, as the high-level Interim Committee began its deliberations, he deputed James Franck, the head of Met Lab’s chemistry section, to write a report examining the probable consequences of the bomb’s use. Franck had serious reservations about using the bomb, and had in fact exacted a promise from Compton, in 1942, that, if an American bomb was ready before Germany or another nation had one, Franck could object to its use at the highest level of government. Franck, who was fondly called ‘Pa’ by his co-workers and had a reputation for rectitude, rushed to his conclusions, and sent his thirteen-page report to Secretary of War Stimson on n June—though, as things turned out, it did not reach Stimson’s desk.30

Franck knew the reasons why many were promoting the use of the bomb, or he anticipated them with remarkable acuity. Some said that using bombs would end the war quickly and thus save American lives. Franck doubted that the first generation of nuclear weapons would be powerful enough to discourage the Japanese from continuing the fight. Moreover, even if the bombs did shorten the war and thus keep American soldiers alive, that benefit ‘may be outweighed by the ensuing loss of confidence and wave of horror and repulsion’ the world would feel if the bombs were dropped. The huge expense for the Manhattan Project, mentioned to Szilard by Byrnes, did not require the bombs’ use; the American public would understand ‘that a weapon can sometimes be made ready only for use in an extreme emergency’, and that nuclear weapons were in this category. The ‘compelling reason’ to build the weapon had been the scientists’ fear that Germany might be building one too, but that was no longer an issue. Above all, using the bomb against a Japanese city would so shock the world as to make future control of nuclear weapons unlikely. The bomb was ‘something entirely new in the order of magnitude of destructive power’. Given that, the way forward was to arrange a demonstration of the weapon in ‘the desert or [on] a barren island’, to which representatives from all nations, including of course Japan and the Soviet Union, would be invited. If the Japanese saw the awful power of the bomb, they might surrender. If the Russians and others saw that the Americans had the bomb but were too merciful to use it, they might be persuaded to place nuclear weapons work under international control.31

Deterrence

-

abhishek_sharma

- BRF Oldie

- Posts: 9664

- Joined: 19 Nov 2009 03:27

Re: Deterrence

Continuing ...

-

Prem Kumar

- BRF Oldie

- Posts: 4245

- Joined: 31 Mar 2009 00:10

Re: Deterrence

I rest my caseabhishek_sharma wrote:Continuing ...

Given that, the way forward was to arrange a demonstration of the weapon in ‘the desert or [on] a barren island’, to which representatives from all nations, including of course Japan and the Soviet Union, would be invited. If the Japanese saw the awful power of the bomb, they might surrender. If the Russians and others saw that the Americans had the bomb but were too merciful to use it, they might be persuaded to place nuclear weapons work under international control.31

-

abhishek_sharma

- BRF Oldie

- Posts: 9664

- Joined: 19 Nov 2009 03:27

Re: Deterrence

From the book cited above:

Military and government officials either remained unaware of the Franck Report or ignored it. Still, dissent continued. A gas diffusion engineer named O. C. Brewster got a letter through to Stimson on 24 May in which he insisted that, if the United States dropped the bomb, ‘we would be the most hated and feared nation on earth’. George Harrison, Stimson’s special assistant, wrote to his boss on 26 June of scientists’ concerns about the bombs’ use leading to a nuclear arms race. In July, Szilard tried again, circulating at the Met Lab a petition calling on the government to refrain, ‘on moral grounds’, from using the bomb against Japanese cities. He got fifty-three signatures at first, then toned down his language slightly and gained seventeen more. But he could not win over the Lab’s chemists, nor could he persuade Oppenheimer or Edward Teller, both at Los Alamos, to sign. (Oppie refused even to circulate the document.) The petition went through channels to Groves, who sat on it until i August, when he sent it to Stimson. President Truman, who had been in Potsdam and was then returning home aboard ship, never saw it.32

There were also several high-ranking doubters, men involved in atomicbomb decisionmaking, who shared, perhaps independently, the scientists’ concerns about dropping the bomb on Japanese cities, or who had different concerns that nevertheless brought them to some of the same, troubled conclusions. With Barton J. Bernstein, we can probably dismiss the postwar statement of wartime opposition to using the bomb made by Dwight Eisenhower. Bernstein casts similar doubt on post facto remarks criticizing the attacks by three of the four members of the 1945 Joint Chiefs of Staff: Admiral Ernest King, Army Air Force General Henry Arnold, and Admiral William Leahy, the chairman of the chiefs whose 1950 memoir, incongruously endorsed by Truman, described the use of the bomb as barbaric. The fourth member of the JCS, George Marshall, did privately urge Stimson, on 29 June, to confine use of the bomb to a genuinely military target. When the administration instead agreed to target Hiroshima and other cities, Marshall kept his counsel. Joseph Grew, the Undersecretary of State and former Ambassador to Japan, urged Truman in late May to signal the Japanese that even in surrender they could retain control of their political system, meaning that the office and the person of the Emperor would be preserved. Grew’s proposal came in the aftermath of the latest firebombing attack on Tokyo; the atomic bomb lurked only in shadow form behind his argument to the President. Truman sent Grew off to see Stimson and several military leaders, who objected that such a concession would signal weakness to the Japanese even as the battle continued for Okinawa. Most forceful among the dissenters was Ralph Bard, undersecretary of the navy and a member of the Interim Committee. Bard was convinced, as he wrote to George Harrison on 27 June, that the Japanese were looking for a way to capitulate. If perhaps Japan was warned about the bomb, even a few days before it was to be used, and if perhaps the President could make ‘assurances’ to Tokyo regarding the Emperor, the Japanese would surrender unconditionally. Bard saw nothing to lose by trying.33

7. The dismissal of doubt

...

Franklin Roosevelt, typically cautious and non-committal about nearly anything not requiring an immediate decision, did apparently wonder to Vannevar Bush, in September 1944, whether the bomb ‘should actually be used against the Japanese or whether it should be used only as a threat with full-scale experimentation in this country’. He was thinking aloud, advocating for the devil, trying something new on for Bush—for otherwise there is nothing in the record to suggest that Roosevelt would have hesitated to use the weapon he himself had authorized and had discussed without reservation many times with Bush, Stimson, Churchill, and others. The assumption that the bomb would be used also governed the deliberations of Truman’s Interim Committee. Established in late April at the behest of the President, the committee was broadly charged by Stimson to ‘study and report on the whole problem of temporary war controls and later publicity, and to survey and make recommendations on postwar research, development and controls, as well as legislation necessary to effectuate them’. Its members were Stimson, in the chair (George Harrison served as chair when Stimson could not be present), Bard, Bush, Conant, Karl Compton, and Undersecretary of State William Clayton. Attached to the committee was a Scientific Panel, including Oppenheimer, Ernest Lawrence, Arthur Compton, and Enrico Fermi. James Byrnes was added as the personal representative of the President.34

...

Even more striking is the speed with which the first formal discussion of the committee, on 31 May 1945, went in the direction of the future of nuclear power and prospects for its international control. The membership talked for over three hours that morning hardly mentioning Japan, though just before lunch there was a conversation about how to handle the Russians. When at last the subject of Japan came up, number eight on an agenda with eleven substantive items, it was encapsulated in the title ‘Effect of the Bombing on the Japanese and their Will to Fight’. The subsequent discussion concerned similarities and differences between the atomic bombing and ongoing non-nuclear strikes, possible targets, and whether to drop just one bomb at a time or several at once. (Groves, who was present, and was ultimately invited to every Interim Committee meeting, urged use of a single bomb, in part because the effect of a multiple strike ‘would not be sufficiently distinct from our regular bombing program’.) No one at this point voiced reservations about using the bomb. In summarizing the deliberations, R. Gordon Arneson, who took notes at the meeting, recorded ‘general agreement’ with the conclusion that ‘we could not give the Japanese any warning’ that the bomb was coming.35

-

abhishek_sharma

- BRF Oldie

- Posts: 9664

- Joined: 19 Nov 2009 03:27

Re: Deterrence

Continuing ...

When a scientists’ Target Committee placed the city of Kyoto at the top of its list of objectives for an atomic-bomb crew, Stimson, who had twice visited it, demanded its removal: Kyoto was a cultural and religious center that would become, if destroyed, an example of American cruelty, and, if spared, a symbol of American decency and restraint. No amount of entreaty from Groves would persuade the secretary to put Kyoto in the cross hairs. Stimson also took it on faith that civilians should be spared, ‘as far as possible’, from the weapons of war.40

‘As far as possible’—there was a loophole that admitted morally dubious acts backlit by self-delusion. In gravitas, in the regard with which others held him, in his willingness to allow his decisions about the bomb at least occasionally to trouble him, he was the government’s counterpart to Robert Oppenheimer (who found Stimson impressive). The bomb, Stimson jotted in notes to himself before his first meeting with the Interim Committee, ‘may destroy or perfect International Civilization and ‘may [be] Frankenstein or means for World Peace’. But, if there was distress in these perceptions, so alien to the likes of Groves and Byrnes, there was also an unwillingness to allow them to prevent the bombs from being used. Stimson needed to discuss how and where the bomb(s) would be dropped, and he was genuinely concerned about the consequences of dropping the bombs on Japanese cities. He did not, however, question the need to drop them, never recognizing any ‘profound qualitative difference’ between them and non-nuclear weapons, as Martin Sherwin puts it. Stimson guided the Interim Committee to its decision that the bomb should be used as soon as it was ready, and it was he, along with Marshall, who formally authorized the 20th Air Force to ‘deliver’ the bombs to Japan. Perhaps he extinguished his doubts with his strenuous effort to keep Kyoto off the target list; having secured the safety of the Buddhist temples and shrines and the lives of the citizens of Kyoto, Stimson could tell himself that he had acted decently, even morally, or had gone as far as circumstances would allow. Perhaps instead, as Sherry argues, he deluded ‘himself that “precision” bombing remained American practice’ in 1945. In any event, to gain the surrender of Japan, Stimson wrote in 1947, it seemed necessary to administer a ‘tremendous shock which would carry convincing proof of our power to destroy’ Japan. That meant the bomb.41

Harry Truman relied on Stimson for guidance about the bomb, so it is no surprise that the President came to share his secretary’s self-delusion about its target. Overwhelmed by the job—on the first afternoon following Roosevelt’s death he told reporters that he ‘felt like the moon, the stars, and the planets had fallen’ on him—Truman exhibited on the atomic-bomb issue a combination of feigned indifference and zealous over-involvement characteristic of the insecure. There is little evidence that he saw the bomb as a moral matter, at least before the second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki on 9 August. He nevertheless felt compelled to tell himself, like Stimson, that the atomic bombs whose use he authorized, or to whose use he acceded, were to be aimed at military targets. It was in a mid-May 1945 meeting with the President that Stimson declared that Air Force firebombings had targeted the Japanese military, and that ‘the same rule of sparing the civilian population should be applied as far as possible to the use of any new weapons’, like the atomic bomb. Two weeks later came the Interim Committee meeting that resolved, according to Stimson, that the ‘most desirable target’ of the bomb ‘would be a vital war plant employing a large number of workers and closely surrounded by workers’ houses’. Truman accepted this recommendation. After conferring with Stimson about the bomb again at Potsdam, on 25 July, Truman wrote in his diary:

I have told the Secretary] of War, Mr Stimson, to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children. Even if the Japs are savages, ruthless, merciless and fanatic, we as the leader of the world for the common welfare cannot drop this terrible bomb on the old capital [Kyoto] or the new [Tokyo]. He and I are in accord. The target will be a purely military one.

Anyone who knew, as Stimson and Truman did, what the firebombs had done to Hamburg, Dresden, and Tokyo, and what the test of the plutonium bomb in New Mexico had revealed nine days earlier, also knew that these weapons unleashed upon cities did not magically kill only their military inhabitants, or destroy factories and ‘workers’ houses’ while sparing tea shops, hospitals, and the homes of teachers. Here, again, was self-deception—undertaken at the highest level and on the most critical of issues. Probably, like Stimson, Truman told himself that sparing Kyoto (and, belatedly, Tokyo) absolved him of charges that he was targeting innocents. Having thus persuaded himself that he was merely engaged in the accepted strategic practice of war, Truman slept soundly on those midsummer nights.42

-

abhishek_sharma

- BRF Oldie

- Posts: 9664

- Joined: 19 Nov 2009 03:27

Re: Deterrence

Continuing ...

10. Why the bombs were dropped

How had it come to this? In the months and years after Hiroshima, historians and other commentators offered a variety of explanations for the US decision to use the atomic bomb against Japan. One of them, heard increasingly in recent years, is that white American racism caused, or at minimum enabled, the United States to use a devastating weapon on the Japanese, brown people whom they considered inferior to themselves, barbaric in their conduct of war, and finally subhuman—‘a beast’, as Truman put it. It is certainly true, as John Dower, Ronald Takaki, and others have demonstrated, that the Pacific War was fought with a savagery unfamiliar to those who had engaged each other in Europe, where enmities were bitter but vitiated by the fact that the adversaries were white. On the west coast of the United States, beginning in 1942, Japanese-Americans were rounded up and placed in internment camps. There was no means test given for loyalty: ‘a Jap is a Jap’, insisted General John L. DeWitt, head of the US Western Defense Command, and all ‘Japs’ were potentially treacherous. Or, as the Los Angeles Times had it: ‘A viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched—so a Japanese-American, born of Japanese parents, grows up to be a Japanese not an American.’ Home front officials and publications depicted Japanese and Japanese-Americans as insects, vermin, rodents, and apes, and in this way inspired exterminationist fantasies, for who could object to the eradication of lice, spiders, or rats? Marshall Fields department stores in Chicago bought a two-page newspaper ad depicting a simian-like Japanese soldier cringing beneath the shadow of a bomber; the caption asked, ‘Little men, what now?’ The Elks Lodge in Harrisburg, Illinois, promised ‘to knock out Hirohito but it won’t be easy... Rats are dangerous to the last corner.’ Even more sophisticated publications erased the distinction between soldiers and civilians in Japan. According to the New Republic: ‘The natural enemy of every American man, woman and child is the Japanese man, woman and child.’ It was race that mattered, blood that told; no Japanese, anywhere, could or should be spared.54

The Americans who fought Japanese in the Pacific theater were, if anything, even more scathing in their characterizations of them. Admiral William F. (‘Bull’) Halsey commander of the US South Pacific Force, told reporters that ‘the only good Jap is a Jap who’s been dead six months’. Not to be outdone, Halsey’s Atlantic counterpart, Admiral Jonas H. Ingram, explained that, ‘if it is necessary to win the war, we shall leave no man, woman, or child alive in Japan and shall erase that country from the map’. ‘When you see the little stinking rats with buck teeth and bowlegs dead alongside an American, you wonder why we have to fight them and who started this war,’ said Lieutenant General Holland M. (‘Howlin’ Mad’) Smith. ‘The Japanese smell,’ he added. ‘They don’t even bleed when they die.’ Soldiers took their cues from their officers, whose views in any case reinforced their own about the kind of enemy they were fighting. Robert Scott Jr., author of the bestseller God Is My Co-Pilot, relished combat in Southeast Asia. ‘Personally’ he wrote, ‘every time I cut Japanese columns to pieces... strafed Japs swimming from boats we were sinking, or blew a Jap pilot to hell out of the sky, I just laughed in my heart and knew that I had stepped on another black-widow spider or scorpion.’ E. B. Sledge, island hopping with the marines in the South Pacific, marveled at the refusal of Japanese soldiers to surrender and noted many examples of’trophy-taking’ by his fellow marines—the result, he thought, of a ‘particular savagery that characterized the struggle between the Marines and the Japanese’. Marines prized enemy ears, fingers, hands, and, most often, gold teeth:

The Japanese’s mouth glowed with huge gold-crowned teeth, and his [American] captor wanted them. He put the point of his kabar on the base of a tooth and hit the handle with the palm of his hand. Because the Japanese was kicking his feet and thrashing about, the knife point glanced off the tooth and sank deeply into the victim’s mouth. The Marine cursed him and with a slash cut his cheeks open to each ear. He put his foot on the sufferer’s lower jaw and tried again. Blood poured out of the soldier’s mouth. He made a gurgling noise and thrashed wildly.

Compassion for Japanese was rare, Sledge noted, and scorned by most American soldiers as ‘going Asiatic’. 55

Re: Deterrence

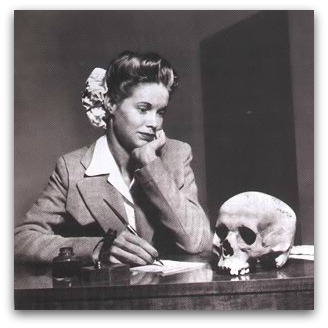

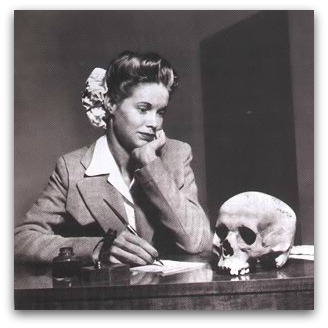

An American girl with a Japanese skull sent by her Marine boyfriend in ww2. How cute.

-

member_19686

- BRFite

- Posts: 1330

- Joined: 11 Aug 2016 06:14

Re: Deterrence

The Russo-Japanse War, at the beginning of this century, made the Russians fear that their Christian society was under a dual attack, from the heathen Japanese without and from the infidel Jews within. In 1905, following the humiliating defeats on land and sea that the Japanese had inflicted on the Russian empire, the great writer Leo Tolstoy offered an explanation for his country's setbacks. In a letter to a friend, he wrote:

This debacle is not only of the Russian army, the Russian fleet and the Russian state. . . . The disintegration began long ago, with the struggle for money and success in the so-called scientific and artistic pursuits, where the Jews got the edge on the Christians in every country and thereby earned the envy and hated of all. Today the Japanese have done the same thing in the military field, proving conclusively, by brute force, that there is a goal which Christians must not pursue, for in seeking it they will always fail, vanquished by non-Christians.8

In these few sentences Tolstoy, otherwise famous for his humanism and morality, expressed the old Christian fear of the flourishing infidel, whose outstanding representatives in his time were the Jews and the Japanese.

A British writer, T. W. H. Crosland, commenting on the Japanese victories on the Manchurian front in 1904, described as follows the physical features of the Japanese in order to illuminate their low morality:

A stunted, lymphatic, yellow-faced heathen, with a mouthful of teeth three sizes too big for him, bulging slits where his eyes ought to be, blacking-brush hair, a foolish giggle, a cruel heart, and the conceit of the devil-this, O bemused reader, is the authentic dearly-beloved "Little Jap" of commerce, the fire-eater out of the Far East, and the ally, if you please, of John Bull. . . . It is a grave question whether Japan, with her marvellous gifts of imitation, her extraordinary energy, her cunning rapidity, and her total want of conscience, is in the least likely to become "a world power" of the kind that Europe is likely to find useful or satisfactory. Indeed the only restraints that could be put upon her are the restraints of the Christian religion. Can she be brought to submit to them? Does she desire in her heart to submit to them? Will she ever be other than pagan and heathen and unconscionable under the surface? the answer is: No...

Demonizing the Other: Antisemitism, Racism and Xenophobia edited by Robert S. Wistrich

http://books.google.ca/books?id=G-19lB3 ... ty&f=false

In Washington's "eyes, the worst Japanese war crime was the attempt to cripple the white man's prestige by sowing the seeds of racial pride under the banner of Pan-Asianism." The "International Military Tribunal for the Far East. . . . accused Japan of, among other things, racial arrogance' in challenging the stability of the status quo that existed under Western rule.

When Japanese racial atrocities targeting Europeans and Euro-Americans were revealed, London noticed that "generally speaking . . . there has been a relative lack of Chinese interest in the British and American disclosures" ; worse it was noted forlornly, "it is also possible that the Chinese appreciate-and secretly sympathize with-the fact that one Japanese aim in perpetrating these atrocities was the humiliation of the white man, as part of the plan for his expulsion from East Asia."14 In a "secret" memorandum from India, a British official cautioned that "publicity" about the "specific question of ill treatment of white captives should not be undertaken for the present, though a statement in general terms might be issued without reference to race of prisoners." Hence, it was decided that "the point is to emphasise by every means Japanese barbarity towards other Asiatics, but not to bolster up [the] Japanese self-proclaimed role as defender of Asiatics by putting out stories of their barbarous treatment of Europeans."15

Thus, in the heat of war the shoots of postwar racial policy and the forced retreat from white supremacy were already evident: a compelled assertion of equality between European and non-European peoples, and further, an assertion of "nonracialism", denying even the relevance of a characteristic that heretofore had been proclaimed from on high.

J. P. S. Devereux, a proud Marine major, "would never willingly have lowered himself to talk to a yellow man on equal terms. Now he had to learn to speak lower than low, in the voice of unconditional surrender." He was not alone, as "the yellow man returned the white man's hate and contempt" in spades. In the early days of captivity a Japanese officer was holding a handkerchief to his nose. A POW sergeant asked him if he had a cold. "Baka! Stupid! said the Japanese. You smell bad, you smell very bad." Later the captor said his prisoner did not smell so terribly. "Now you smell O.K. You no eat meat since you become pu-ri-so-na. This story could be read another way: The Japanese liked their white prisoners to be starving." And it can be read yet another way: treacherous tropes of insult traditionally used by Europeans and Euro-Americans - such as suggesting that some groups emit foul odors - against Africans particularly, were now being turned back against the perpetrators by Asians.

Race War: White Supremacy and the Japanese Attack on the British Empire By Gerald Horne

http://books.google.ca/books?id=q_DVIIL ... navlinks_s

. . . Orientals must be kept in their native East till the fall of the white race. Sooner or later a great Japanese war will take place, during which I think the virtual destruction of Japan will have to be effected in the interests of European safety. The more numerous Chinese are a menace of the still more distant future. They will probably be the exterminators of Caucasian civilisation, for their numbers are amazing. But that is all too far ahead for consideration today.

- H. P. Lovecraft, Sept. 30, 1919

-

sanjaykumar

- BRF Oldie

- Posts: 6116

- Joined: 16 Oct 2005 05:51

Re: Deterrence

Thanks muchly for that google book Race War.

And Lovecraft was amazingly prescient, too bad he was as much of a racist as any c.f. At the Mountains of MAddness perhaps the finest work in its genre.

And Lovecraft was amazingly prescient, too bad he was as much of a racist as any c.f. At the Mountains of MAddness perhaps the finest work in its genre.

Re: Deterrence

Folks try to find cartoons relevant to India. Eg Paki cartoons about stereotypes.

-

abhishek_sharma

- BRF Oldie

- Posts: 9664

- Joined: 19 Nov 2009 03:27

Re: Deterrence

Continuing ...

The men who made the decision to drop atomic bombs and decided where to drop them shared the sharply racialized sentiments of their officers and fighting men. ‘Killing Japanese didn’t bother me very much at that time,’ recalled Curtis LeMay. ‘So I wasn’t worried particularly about how many people we killed in getting the job done.’ The South Carolinian Byrnes routinely referred to ‘niggers’ and ‘Japs’. Discussing the Hiroshima bombing with Leslie Groves on the day after it had happened, Chief of Staff George Marshall cautioned against ‘too much gratification’ because the attack ‘undoubtedly involved a large number of Japanese casualties’. Groves replied that he was not thinking about the Japanese but about those Americans who had suffered on the Bataan ‘Death March’. Truman himself was a casual user of racial epithets for African Americans, Jews, and Asians. The Japanese, in his lexicon, were ‘beasts’, ‘savages, ruthless, merciless, and fanatic’.56

While there is no question that white Americans, at least, exhibited anti-Japanese racism, it is unlikely that racism explains why the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, though perhaps it helped policymakers justify the decision to themselves after it had been made. The coarsening of ethical standards concerning who got bombed and how was virtually universal by 1945. Americans hated Japanese more than they hated Germans, but that did not prevent them from attacking Hamburg and Dresden with firebombs, targeting the citizens of these cities just as surely and coldly as those in Hiroshima and Nagasaki were targeted—or, for that matter, the citizens of London and Shanghai. There is no evidence to suggest that the Americans would have foregone use of the atomic bomb on Germany had the weapon been ready before V-E Day. If Berlin or Bonn or Stuttgart had been the a-bomb’s target, Groves could not have satisfied himself afterwards that Bataan had been avenged, but he might instead have mentioned Rotterdam, the Battle of the Bulge, or even Auschwitz, as he put aside all possible remorse. Or he and the others could have said that the atomic bomb had ended the European war more quickly and thus saved lives, American and enemy, as they would say about the atomic bombings of Japan. The war on both fronts had by 1945 reached a level of savagery that matched even the poison of anti-Asian racism.

A rather stronger case can be made for the American use of atomic bombs as a way of compelling the Soviets to behave more cooperatively in negotiations concerning especially Eastern and Central Europe, and as a way of ending the war quickly and thus foreclosing a major role for the Soviets in the occupation of Japan. The argument for ‘atomic diplomacy’, as this is called, has been made most forcefully down the years by Gar Alperovitz, though others have put forward their own versions of it. The case made by these ‘revisionists’ relies on establishing that Japan was militarily defeated by the summer of 1945, that the ‘peace faction’ of the Japanese government was assertively pursuing terms of surrender by then—chiefly a guarantee of the emperor—and that US policymakers knew that Japan was beaten and that the peace faction’s exploration of terms had imperial backing, were specific and sincere, and thus worthy of taking seriously. (This explains the revisionists’ use of the 1963 Eisenhower quotation: ‘It wasn’t necessary to hit them with that awful thing.’) The Americans also knew that a Soviet invasion of Manchuria and north China, promised by Stalin for August, would destroy what remained of Japan’s will to fight on and in this way allow the Soviets to help shape the postwar Japanese political economy. Rather than permit this, and in the hopes of making the Russians more agreeable in negotiations elsewhere, the Americans dropped the atomic bombs, needlessly and perforce cruelly, on a prostrate nation.57

There is plenty of evidence that key US decisionmakers linked the bomb to their effort to intimidate the Soviet Union. Stimson, like Truman and Byrnes, thought of diplomacy as a poker game, in which the atomic bomb would prove part of’a royal straight flush’ or the ‘master card’, and in mid-May Stimson told Truman, regarding the proposed (and delayed) summit at Potsdam, that, when it finally convened, ‘we shall probably hold more cards in our hands... than now’, meaning a successfully tested bomb. Byrnes was troubled at the thought of the Russians ‘get[ting] in so much on the kill’, as he put it. He told Navy Secretary James Forrestal that he ‘was most anxious to get the Japanese affair over with before the Russians got in, with particular reference to Dairen and Port Arthur. Once in there, he felt, it would not be easy to get them out.’ Byrnes later recalled wanting ‘to get through with the Japanese phase of the war before the Russians came in’. He also assured Special Ambassador Joseph Davies at Potsdam ‘that the atomic bomb assured ultimate success in negotiations’ with the Russians, over German reparations and presumably other things. And Truman’s sense of heightened confidence on learning of the Alamogordo test, his new assertiveness with Stalin, and his desire to rethink the matter of Soviet involvement in the war against Japan, all indicate the extent to which the bomb made an impression on the President and planted it firmly in the diplomatic realm.58

-

RKumar

Re: Deterrence

Directly from China's SIIS Global review ... copying in full to preserve the article... Sorry if it is already posted

China-Pakistan Nuclear Relations after the Cold War and Its International Implications

Author : ZHANG Jiegen

Research associate, Pakistan Study Centre, Institute of International Studies, Fudan University.

China-Pakistan Nuclear Relations after the Cold War and Its International Implications

Author : ZHANG Jiegen

Research associate, Pakistan Study Centre, Institute of International Studies, Fudan University.

Introduction

Though China-Pakistan relations have been viewed by both countries as ‘all-weather, time-tested’ strategic cooperative partner all along, there are comparatively few studies relating to this bilateral relations in the Chinese community of international studies. Considering the extraordinary importance of Pakistan in the integral structure of China’s foreign relations, this kind of phenomenon in China’s academic circle is quite abnormal. The year 2011 marked the sixtieth anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Pakistan. There are a series of papers relating to China-Pakistan relations published for celebration. However, these papers are mainly macro-level studies and focused on the strategic aspects of the bilateral relations, lacking in in-depth studies on detailed aspects and specific issues in China-Pakistan relations.

Context

In retrospect of China-Pakistan relations in the past sixty years, it is not difficult to conclude that security relations is the most important aspect in the bilateral relations, which can be viewed as the key pillar of the whole China-Pakistan relations. Generally speaking, China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation is an unavoidable subject when it comes to talks about security relations between them. Nevertheless, due to the sensitivity of this topic in China, very few scholars have been doing some research relating to China-Pakistan nuclear relations by far. Consequently, there is a serious lack of special research on this important issue from Chinese perspective. Unfortunately for China, with the constant development of Chin-Pakistan nuclear relations, overseas media often exaggerates the facts and suspects the real intention of China following each step of China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation. At the same time, quite a few scholars from India and Western countries have published many papers and articles in academic journals or newspapers. However, being subject to the discriminatory standpoints, the media and academic circles from India and the Western countries often misunderstand the China-Pakistan nuclear relations. Moreover, some scholars even criticize the ordinary nuclear cooperation between China and Pakistan intentionally. This paper aims at arguing against these misperceptions. To do so, it starts with the review of the history of China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation and then tries to study the main factors influencing China-Pakistan nuclear relations objectively. After that, the paper probes into the future of China-Pakistan relations and puts forward the author’s thinking about its international implications.

I. The External Perspectives on China-Pakistan Nuclear Relations

Both the structure of the international system and the geopolitical situation of South Asia have changed greatly after the Cold War, but the traditional friendly security relation between China and Pakistan still preserves its original status. Undoubtedly, the friendly cooperation on nuclear issue plays a pivotal role in the process of boosting mutual confidence and stabilizing strategic cooperation between China and Pakistan. To China and Pakistan, as far as the nuclear cooperation is concerned, it not only results from given history background, but also is rooted in the objective review of each other’s strategic interests by the two countries. Ignoring the history background and being short of understanding the strategic needs of China and Pakistan, scholars from India and Western countries often evaluate China-Pakistan nuclear relations from external factors or still understand this relationship with the Cold-War mentality. As a result, it’s inevitable for them to misunderstand the friendly cooperation between China and Pakistan in the nuclear field with the discriminatory vision.

The first and most popular argument about China-Pakistan relations is to understand the nuclear ties between them from the traditional realistic point of view. “Balance of power” is the core concept for these scholars to analyze it. T.V. Paul, James McGill Professor from McGill University of Canada, is a typical supporter for this argument. In his words, “China has continued to interpret its nonproliferation commitments narrowly with regard to supplying nuclear and missile-related materials to its key allies in the developing world, especially Pakistan”. He argues that “Beijing’s motivations in transferring materials and technology to Pakistan derive largely from Chinese concerns about the regional balance of power and are part of a Chinese effort to pursue a strategy of containment in its enduring rivalry with India”. He adds that “if acute conflict and an intense arms race between India and Pakistan persist, India would continue to be bracketed with its smaller regional rival Pakistan and not with China”.[1] His viewpoint seems logical and often is cited by some other analysts working on China’s non-proliferation policy. However, he overlooked two key important facts which have been going along from the end of the Cold War till now. One is that China has made great progress in participating in international non-proliferation regime. Another fact is that Sino-Indian relations have continued to be reconciled and improved in the post-Cold War era.

The second misperception on China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation is to overstate the nuclear cooperative depth between China and Pakistan, which views the nuclear relation between China and Pakistan as ‘nuclear alliance’. In a paper titled “China-Pakistan Nuclear Alliance”, Siddharth Ramana, a research officer from the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies based in India, points out that there exits a security alliance between China and Pakistan. He says that “this alliance was to take the form of nuclear cooperation, especially in the aftermath of the Indian nuclear test of 1974”. In his perspective, China makes use of this alliance to “achieve twin strategic objectives of encirclement of India, and a proliferation buffer, wherein Pakistan in turn further proliferate Chinese nuclear technology, giving China leeway in investigations”. He argues that China does not extend its nuclear umbrella to Pakistan but uses Pakistan as an “extended deterrence proxy” towards India.[2] This perception exaggerates China’s strategic objectives on the one hand, and on the other, neglects not only the equal essence of the China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation but also Pakistan’s strategic independence in the nuclear area.

A more discriminatory argument comes from Ashley J. Tellis, a Washington D.C.-based influential scholar. As a steadfast supporter of U.S.-India Civil Nuclear Agreement, he employed a totally different criterion to criticize China-Pakistan civil nuclear cooperation. From his view, the differences between the two are significant because “unlike the U.S.-India civilian nuclear initiative, whose terms were publicly debated, the Sino-Pakistani agreement is a secret covenant, secretly concluded” and “whereas the United States respected the international nonproliferation regime by requesting a special NSG waiver to permit nuclear trade with India, China seeks to short-circuit the NSG rather than appeal to its judgment”. So he argues that “it’s time for the United States to raise its voice” to “convey to China its strong concern about the planned reactor sale to Pakistan”.[3] From the Chinese perspective, his arguments not only exhibit a hegemonic logic but also show the western intention to infringe on the independent right to develop relations with its strategic partner.

Contrasting with the three arguments mentioned above, the view of Mark Hibbs looks much softer. He mainly argues that China’s nuclear deal with Pakistan reflects “the growing confidence and assertiveness of China’s nuclear energy program”. In his opinion, “China’s increasingly ambitious nuclear energy program is becoming more autonomous” and “China will likely become the world’s second-biggest nuclear power generator after the United States by 2020”. In this context, he concludes that China’s nuclear export to Pakistan is a part of China’s nuclear export strategy and the political function of the nuclear trade between China and Pakistan can’t be exaggerated. [4] To some extent, I partly agree with him. But I argue that the whole China-Pakistan nuclear relations should be considered comprehensively.

II. A Brief Historical Review of China-Pakistan Nuclear Relations

One important reason that some foreign scholars misread the China-Pakistan nuclear relations is that they do not take into account the historical background of the development of China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation, and therefore, with the time going on, do not see the actual changes of China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation. In this case, it is not difficult to understand that as mentioned earlier, some scholars believe that China has been engaged in nuclear proliferation in South Asia even today. Frankly speaking, this phenomenon is related to the opaque nuclear cooperation conducted by China and Pakistan. However, this ambiguity just mainly existed in the era of the Cold War. In this special historical context, it is unfair to evaluate China-Pakistan nuclear relations of that period with today’s nuclear non-proliferation requirements when it comes to such sensitive areas as nuclear cooperation. After the Cold War, it is extremely unscientific to look at the China-Pakistan nuclear relations at post-Cold War era, especially in the new century with the China-Pakistan cooperation model in the Cold War. Overall, divided by the two historic events, the end of the Cold War and South Asia Nuclear Test, the development of China-Pakistan nuclear relationship has gone through three historical periods.

The first period is from the mid-1970s to the end of the Cold War. As early as in 1950, Pakistan formally recognized the People's Republic of China, being the first third-world country in the world and also the first Islamic country to establish formal diplomatic relations with China. However, a close political relationship between China and Pakistan began only after the Sino-Indian War in 1962; it is a premise for the China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation later on. Pakistan's nuclear program started much later than that of India. Indeed, it can be traced back to the early 1970s. Fundamentally speaking, Pakistan develops its nuclear program to safeguard its own security, as its conventional military power is weaker than India and India has been secretly developing nuclear weapons. Seeking cooperation with the outside power is an important way to develop its nuclear weapons. Due to the increasingly close China-Pakistan political relations, Pakistan opens the door of the China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation at the beginning of its nuclear program, and China is also willing to carry out cooperation with Pakistan in the nuclear area. It is obviously inconsistent with historical facts that western scholars tend to ignore Pakistan’s inherent drive to seek nuclear cooperation with China, while blaming China for engaging in nuclear proliferation in South Asia through nuclear cooperation with Pakistan. It is a difficult thing to confirm the specific starting point of nuclear cooperation between China and Pakistan, but the last will and testament of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto reveals that the China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation began in 1976 and he has made 11 years of efforts to work it out prior to this.[5] The conversation between Bhutto and Henry Kissinger, the former U.S. Secretary of State, reveals that during this period, China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation was mainly focused on the nuclear reprocessing technology, instead of uranium enrichment technology.[6] What pushed further nuclear relationship between China and Pakistan was an official China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation agreement signed in 1986; it was the agreement that forms the close relationship of nuclear technology transfer between China and Pakistan.[7] China and Pakistan has never officially made this agreement public and disclose the specific transfer content of the nuclear technology. Western scholars draw the conclusion that China helped Pakistan develop nuclear weapons during this period mainly based on the information from intelligence agencies of the United States as well as the media report, which might be suspected and exaggerated.

The end of the Cold War witnessed the beginning of the second historical period of China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation. Compared to the Cold War era, the external environment faced by the China-Pakistani nuclear relationship has changed a lot. There are two major changes: First, along with the accelerated process of world arms control and nuclear disarmament, China has gradually integrated into the international nuclear non-proliferation regime, which results in more and more constraints on its nuclear cooperation with Pakistan; Second, the United States has taken more stringent measures on arms control, and has imposed a series of sanctions on Pakistan and China because of the nuclear-related sensitive products transfer between them. Before an open nuclear test by Pakistan in 1998, the nuclear cooperation between China and Pakistan had been questioned by the western countries, whose intelligence was mainly from the United States. Such accusations included not only transferring the complete nuclear device design model, developing its uranium enrichment program and nuclear weapons-related materials, such as ring magnets, but also gradually focused on criticizing China transferred missiles technology to Pakistan. China formally joined the NPT in 1992, followed by joining the IAEA a year later; therefore, the nuclear cooperation between China and Pakistan has been increasingly under international supervision. China increasingly focuses on its international responsibilities and obligations when developing the traditional friendly nuclear relationship with Pakistan. Therefore, despite the skepticism of the China-Pakistan nuclear relationship, the U.S. government only mentioned in public that China has been helping Pakistan develop nuclear weapons before 1992.[8]

The third historical period of the China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation starts from South Asian open nuclear test in 1998. The nuclear tests in South Asia marked the open nuclear weaponization for India and Pakistan. Despite the provisions of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, only the countries with an open nuclear test before 1967 can be called nuclear weapon states, the fact can not be denied that India and Pakistan have became the two de facto nuclear weapon countries. By then, China-Pakistani nuclear relations had evolved into a relations between a nuclear state recognized by the international nuclear regime and a de facto nuclear state drifting away from the international nuclear regime. After the nuclear tests in India and Pakistan, the international community led by the U.S., implemented nuclear embargo. It encountered difficulties in developing nuclear relationship with the two countries, by the rules or in practice. In addition, China joined the NSG in 2004, which further compressed the space of China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation. Therefore, the China-Pakistan nuclear relationship was inevitably be affected, because this impact was caused by external factors, the nature of the China-Pakistan friendship and cooperation in the nuclear field was not interrupted. On the contrary, with the tremendous progress of Pakistan's nuclear technology and the rapid development of civilian nuclear technology in China, there was a broader space in the field of civilian nuclear energy cooperation between the two countries. In this context, the two countries significantly speeded up civilian nuclear energy cooperation in recent years. In 2005, China began to provide Pakistan with a second nuclear power station, 14 years after the first. Since 2010, China has agreed to continue to construct another two 650 MW nuclear power reactors in Chashma, a place in central Pakistan’s Punjab province, and decided to supply the fifth nuclear reactor to Pakistan. At this point, the nuclear cooperation between China and Pakistan had been no longer in the area of security mainly, but in energy and commercial fields, which was fully under the supervision of the International Atomic Energy Agency. Although still questioned by the West and India, the cooperation process is now irreversible, and will play a positive role in promoting China-Pakistan relations in the new era.

III. The Main Factors Affecting the Development of China-Pakistan Nuclear Relations

China-Pakistan nuclear relationship is an important part of the overall China-Pakistan relations. The perceptions of its importance relating to their respective diplomatic strategy are critical. It is the internal and the most important factor to think about the development and trend of China-Pakistan nuclear relationship in the post-Cold War era. At the same time, every step of the progress of China-Pakistan nuclear relationship affects the nerves of countries in South Asia and related countries outside this region. The international community pays high attention to it, and therefore it can not be free from constraints of external factors.

First, the long-term nuclear cooperation between China and Pakistan is the product of comprehensive and friendly China-Pakistan relations. As mentioned earlier, the cooperation between China and Pakistan on the nuclear issue began in the mid-1970s, and it has been more than 40 years of history by now. During this period, though the international situation has undergone dramatic changes and the international pressure from various sides has never stopped, the friendly relations of the China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation has never been interrupted, and will continue to develop further more. To Pakistan, India is the first prevention object for its national security; however, because of the gap of its national power as well as conventional military power with India, it is a natural choice to develop strategic nuclear power to balance India with outside help. Among the major powers, the United States is certainly important for Pakistan, but the history of the development of US-Pakistan relationship indicates that the United States has never became Pakistan’s trusted ally, while China is completely different. The attitudes towards Pakistan's nuclear issue, which is a vital security interest for Pakistan, reflect the difference. The United States has generally been suppressing the nuclear program of Pakistan, and deregulation happens only when it needs Pakistan's cooperation on regional issues; China has always been respecting Pakistan's security concerns and support Pakistan in maximum with its own resources, within the extent permitted by international rules. As far as China is concerned, Pakistan has an important strategic position in its neighboring environment and diplomacy.[9] But in the relations between China and Pakistan, there have been problems of uneven structure, that is, economic cooperation, personnel exchanges and cultural exchange (‘low politics’), and the political and military cooperation (‘high politics’) has a big gap between the two countries.[10] Because the serious structural imbalance problem exists, it is especially important for long-term friendship cooperation of key areas such as nuclear issue to maintain "all weather" cooperative relationship between the two countries.

Second, South Asian geopolitical situation is the most direct factor that affects China-Pakistan nuclear relationship. Western scholars tend to interpret China-Pakistan relations in this perspective, putting geopolitical considerations as the dominant factor of China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation. While exaggerated, South Asian geopolitical factors really can not be ignored. In South Asia, a basic geopolitical fact is the enduring confrontation between India and Pakistan. After the open nuclear tests of South Asia in 1998, it has evolved into a nuclear confrontation between the two de facto nuclear-weapon states. Because both India and Pakistan are in the process of pursuing a credible nuclear deterrence, strategic stability in South Asia is facing severe challenges.[11] Correspondingly, another geopolitical reality that can not be ignored is the gradually reconciled India-Pakistan relations in recent years. The traditional view is that, as long as the Kashmir issue is not resolved between India and Pakistan, the hostility between the two countries will not come to an end. However, with the rise of India and its changing regional policy, as well as Pakistan's economic difficulties and its desire to change its undeveloped status to narrow the disparity in power with India, the motivation for cooperation is increasingly enhanced in terms of reconciling the hostile relations between the two countries in the security field and the development of cooperation in other areas. In addition, the terrorism situation is getting worse after the Cold War, the terrorists’ seeking to possess mass destruction weapons shadowed this region, which affects not only the China-Pakistan nuclear relationship, but the triangle nuclear relationship among China, India and Pakistan. In facing of the common enemy of terrorism, the non-state actors, China, India and Pakistan also need to find a breakthrough point for cooperation on the nuclear issue.

Third, the international nuclear nonproliferation regime and the trend of nuclear proliferation are important external factors affecting China-Pakistan nuclear relationship. Existing international nuclear non-proliferation regime is based on NPT. According to the NPT definition of the nuclear-weapon state, India and Pakistan, though tested their nuclear weapons openly in 1998, are clearly illegal. Therefore, to develop nuclear relations with these two countries is subject to the constraints of the international nuclear non-proliferation regime. In the period of Cold War, because China did not participate in this regime, while the leading country of the regime, the United States, implemented double standards of the nuclear non-proliferation policy with obvious benefit-oriented policy, China and Pakistan nuclear relations has not been severely constrained by international nuclear non-proliferation regime because of Pakistan’s importance to the United States during that time and the large triangle relationship among China, the United States and the Soviet Union. But after the Cold War, with China's accelerated process of integration into the international nuclear non-proliferation, joining the NPT, CTBT (Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty), China’s transfer of nuclear technology to Pakistan is necessarily under the comprehensive protection of International Atomic Energy Agency. At the same time, the incident of Abdul Qadeer Khan, "the father of nuclear bomb” of Pakistan, allegedly engaged in nuclear proliferation at the beginning of this century, made China-Pakistan nuclear relationship further constrained by the international non-proliferation regime. Since the end of the Cold War, the international non-proliferation regime is more and more accepted by international community, but the momentum of nuclear proliferation in Asia is not optimistic. So far, the countries with more serious nuclear proliferation problems are basically in the surrounding areas of China. This can not fail to affect the development of China's foreign nuclear relationship, including the nuclear cooperation with the friendly and long-term strategic partnership, Pakistan.

Finally, China-Pakistan nuclear relationship has obviously been affected by major power factors, mainly the United States and India. India factor obviously plays a more important role in the early stages of the development of China-Pakistan nuclear relationship. In addition to the obvious geopolitical factors, it is also closely related to India's nuclear weapons development program. India's nuclear weaponization resulted not only in the strategic imbalance in South Asia, but also in China-Indian confrontation in the nuclear area because the main objective of India’s nuclear development is China. The close China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation in the Cold War focused on security is closely related with this. However, with the deepening of the process of nuclear weaponization in India and Pakistan, especially after open nuclear tests of the two states, India’s impact is not as obvious as before in China-Pakistan nuclear relationship. Accordingly, the Unite State’s impact increased significantly in China-Pakistan nuclear relationship. On one hand, the strategic position of Pakistan declines in diplomatic strategy of the United States after the Cold War. On the other hand, the friction between China and the United States in the field of nuclear non-proliferation increased. Between 2000 and 2004, the United States imposed sanctions on Chinese companies up to 50 times in the name of preventing non-proliferation.[12] This nominal friction generated by the nuclear issue, in fact, reflects the United States’ contention of the right to speak as a hegemony with the rapid rise of emerging powers in the international system. Based on the psychology of such precautions, the United States stepped up the cooperation with India in the military field, especially in the nuclear field. In addition to the impact of the China-Pakistan nuclear relationship individually, cooperation between the United States and India becomes important motivation to strengthen nuclear relations between China and Pakistan. The evolution of US-India civil nuclear agreement and the United States positively helping India look for special NSG waiver to permit nuclear trade with India lead to the discrimination of international nuclear regime towards Pakistan. As a key friend of Pakistan, China can not fail to take into account Pakistan’s nuclear cooperation requirements.

IV. Conclusion: Prospect and International Implications

Summing up from the above analysis, although the China-Pakistan nuclear relationship has changed greatly in the post-Cold War era, comparing with that relations in the Cold War era, the suspicion about the persistent China-Pakistan relations has never stopped. Due to the overall configuration of China-Pakistan relations, the respective needs in terms of strategic security and commercial interests for China and Pakistan, and the geopolitical factor, China-Pakistan nuclear relations does not change its characteristics of friendly cooperation in essential. But with the evolution of international nonproliferation regime, China’s nonproliferation policy adjusting by itself, and the changing geopolitical configuration of South Asia, China-Pakistan nuclear relation should also keep up with the times. For China and Pakistan, to further the cooperative relations more closely in nuclear area, some kinds of policy adjustments are necessary and imperative on the premise of keeping the traditional friendly cooperation.

Firstly, both China and Pakistan should not avoid making response to the international pressure straightforward despite that the nuclear cooperation between them is not recognized legally by international nonproliferation regime. On the contrary, if they strive to integrate into the international nuclear cooperative regime positively in the long run, the China-Pakistan nuclear relations may gain wider space to develop in the future. It’s true for China and Pakistan to achieve this goal because of Pakistan’s proliferation record in the past and the limited diplomatic capability of China in the international nonproliferation field. However, China should also help Pakistan look for special NSG waiver to permit nuclear trade with it just as what the U.S. has done for India. Though the possibility of success on this achievement is very slim, the positive meaning of it can’t be denied because of two important reasons. One is that it can keep the mutual communication between China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation and international nuclear regime. Relating to this, another reason is that it can help the international community understand Pakistan’s need to get cooperation from outside and stop criticizing Pakistan blindly with complete bias.

Secondly, the nuclear cooperation between China and Pakistan itself also needs to be institutionalized. So far, the agreement for the China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation still needs to be traced back to the Cold War era, namely 1986 bilateral nuclear cooperation agreement. But now the times of the nuclear cooperation background is changing greatly, the content of the agreement also need to be adjusted. At the same time, the form of agreement should not be in a secretive way, because opaque deal for the nuclear cooperation can only lead to more suspicion from the international community. Corresponding to the US-India nuclear deal, a clear and integral civilian nuclear cooperative agreement, in spite of the difficulty to be recognized by the international community, can reduce the international anxiety for China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation at least.

Thirdly, the goal orientation of the nuclear cooperation should also need to be adjusted. Different from the traditional way that both China and Pakistan pay too much attention to the strategic value, the bilateral nuclear cooperation now should emphasize on commercial value as much as its strategic value, and pay more attention to realize the business value in actual operation. Therefore, the focus of China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation will inevitably be transferred from the traditional security domain to the commercial trade domain.

Looking into the future, as long as the orientation of bilateral nuclear relations between China and Pakistan is clearly made, the nuclear cooperation between them will advance irreversibly due to the traditional basis of friendly bilateral cooperation and the constant practical cooperation in specific areas. With China's overall integration into the international nuclear nonproliferation regime, China’s foreign nuclear cooperation will also be accepted by the international community more and more. At the same time, after Pakistan became the de facto nuclear country, its nonproliferation policy have continued to be changed in a meaningful way and its image of proliferation will also slowly change for better. Therefore, the external environment for China-Pakistan nuclear cooperation will be improved. The benign interaction between China Pakistan nuclear relations and international nonproliferation regime will not only be in favor of enhancing the bilateral nuclear relations, but also produce an active and far-reaching influence on the integral nuclear relations of the whole Asian region.

More details

[1] T. V. Paul, “Chinese-Pakistani Nuclear/Missile Ties and the Balance of Power,” The Nonproliferation Review, Summer, 2003.

[2] Siddharth Ramana, “China-Pakistan Nuclear Alliance: An Analysis,” IPCS Special Report, Vol. 109, August 2011.

[3] Ashley J. Tellis, “The China-Pakistan Nuclear ‘Deal’: Separating Fact from Fiction,” http://carnegieendowment.org/2010/07/16 ... ction/39ow.

[4] See Mark Hibbs, “Pakistan Deal Signals China's Growing Nuclear Assertiveness,” http://www.carnegieendowment.org/2010/0 ... veness/4su.

[5] Yogesh Kumar Gupta, “Common Nuclear Doctrine for India Pakistan and China,” Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, 20 June 2004, http://www.ipcs.org/article/india/common-nuclear- doctrine-for-india-pakistan-and-china-1413.html.

[6] William Burr, “The China-Pakistan Nuclear Connection Revealed,” The National Security Archive, November 18, 2009, http://nsarchive.wordpress.com/2009/11/ ... -pakistan- nuclear-connection-revealed/.

[7] See Siddharth Ramana, “China-Pakistan Nuclear Alliance: An Analysis,” IPCS Special Report, Vol. 109, August 2011.

[8] Archived material, “China's Nuclear Exports and Assistance to Pakistan,” http://cns.miis.edu/ archive/country_india/china/npakpos.htm.

[9] See ZHANG Guihong, “Pakistan’s Strategic Position and the Future of Sino-Pakistan Relations,” South Asian Studies Quarterly, No. 2, 2011.

[10] YE Hailin, “The Problems of Structure Imbalance and its Implications on China-Pakistan Relations in the New Era,” Contemporary Asia Pacific, No. 10, 2006.

[11] Relating to the instability of South Asian nuclear stability, see S. Paul Kapur, Dangerous deterrent: nuclear weapons proliferation and conflict in South Asia, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007.

[12] Daniel A. Pinkston, “Testimony before: U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on China’s Proliferation Practices and Its Role in the North Korea Nuclear Crisis,” US Congress, March 10, 2005, http://www.uscc.gov/hearings/2005hearings/written_ testimonies/05_03_10wrtr/pinkston_daniel_wrts.php.

-

abhishek_sharma

- BRF Oldie

- Posts: 9664

- Joined: 19 Nov 2009 03:27

Re: Deterrence

Continuing ...

When they thought about the bomb, then, Truman and his advisers thought about what it might suggest for relations with the Soviets. But that does not mean that policymakers used the bombs primarily because they wished to manipulate the Russians. They did not know for certain that the Japanese were close to surrender before 6 August, that the addition to the battle of Soviet divisions, the withering American firebombings coupled with the strangling naval blockade, or even the threat of American invasion of the Japanese home islands, would bring speedy capitulation. They did want to end the Pacific War at the soonest possible moment, and one of the reasons they wished to do so was to keep Russian soldiers out of China and Soviet officials out of Japan once the war was over. All this was, however, best described, as Barton Bernstein has put it, as a ‘bonus’ added to the central reason why the Americans dropped the bombs. ‘It seems likely’, writes Michael Sherry, ‘that even had Russian entry been greeted with open arms, rather than accepted as a painful aid and inevitability, the bomb would have been used on the same timetable.’ As much as it mattered to US decisionmakers that the Russians be impressed and even cowed by the use of atomic bombs against cities, that the Russians become more tractable in negotiations, something else mattered more.59

What mattered more was the assumption, inherited by Truman from Roosevelt and never fundamentally questioned after 1942, that the atomic bomb was a weapon of war, built, at considerable expense, to be used against a fanatical Axis enemy. This was ‘a foregone conclusion’, as Leon Sigal has put it, ‘unanimous’ among those most intimately involved in wartime decisionmaking. ‘As far as I was concerned,’ wrote Groves, Truman’s ‘decision was one of non-interference—basically, a decision not to upset the existing plans.’ Groves would subsequently liken Truman’s role to that of ‘a surgeon who comes in after the patient has been all opened up and the appendix is exposed and half cut off and he says, “yes I think he ought to have out the appendix—that’s my decision”.’ A kind of bureaucratic momentum impelled the bomb forward, from imagining to designing to building and then to using. It would have taken a president far more confident, far less in awe of his office and his predecessor, to reflect on the matter of whether the atomic bomb should be used. Even then, it is difficult to picture how the momentum toward dropping the bomb would have been stopped. Truman and his advisers saw no reason not to drop the bomb.60

That they did not had to do with their self-deception—the bomb would be used only on a military target, Stimson and Truman assured themselves—and much to do with the belief, by now hardened into assumption, that non-combatants were unfortunate but nevertheless legitimate targets of bombs. From the first decision by an Italian pilot to aim recklessly at a Turkish camp in Africa, through the clumsy zeppelin bombings and British retaliation for them in the First World War, the ‘air policing’ of British colonies during the 1920s, and the ever more deadly and indiscriminate attacks by the Germans, Japanese, British, and Americans, ethical erosion had long collapsed the once-narrow ledge that had prevented men from plunging into the abyss of heinous conduct during war. Civilians could and would be killed by bombs. To shift the analogy slightly, and, as Richard Frank has written: ‘The men who unanimously concurred with the description of the [atomic bombs’] target experienced no sensation that their choice vaulted over a great divide.’ Indeed, their ‘choice’ was only which Japanese cities should be struck, not whether any of them should be. Once heralded as ‘knights of the air’, American pilots and their crews were now more often regarded as ‘hooligans’, or worse. Still, they were doing their nation’s bidding: three days after Pearl Harbor, two-thirds of Americans polled said they supported the indiscriminate bombing of cities in Japan, a sentiment sustained throughout the war. There was equally little compunction about civilians in Germany, where estimates showed that by 1945 Allied bombers had killed between 300,000 and nearly twice that many. Psychologically, yes, there was something horribly different about the atomic bomb, a single bomb, with what Oppenheimer called its ‘brilliant luminescence’ and its capacity to create such destruction by itself. Functionally, it was merely another step on a continuum of increasingly awful weapons delivered by airplanes.61

-

Christopher Sidor

- BRFite

- Posts: 1435

- Joined: 13 Jul 2010 11:02

Re: Deterrence

There is a reason why Japan surrendered after the August strom and not after the nuclear bombings and that can be summarized in one word Manchuria. Japan went to Manchuria and what Manchuria had become to Japan is the lost story of the war in Asia. It was Japanese invasion of Manchuria and the hostility that it invoked in the liberal circles of USA that led to the war in Pacific. Japan's oil was imported from USA, something in excess of 75% of its total consumption, army+navy+civilian. America did not cut off the oil. No that step was deemed too extreme. What Americans did was it froze all of Japanese assets in America. Without any assets to pay for its oil Japan found itself suddenly cut from the very oil that it needed the most. Hence the need to go south, to the Dutch East Indes which along with Iran, USA and Soviet Caucasus was one of the few regions which produced copious amount of oil in 1930s and 1940s.Johann wrote:CS,Christopher Sidor wrote: In the end by the time the nuclear explosive was weaponized, WWII was practically over. The Soviet invasion of Manchuria showed how weakened the IJA and IJN had become. It took the Soviets only one week to run over a country the size of Western Europe with the complete annihilation of the famed Kwantung Army. This begs to question, why was the bomb eventually used and especially on Japan?

The Soviet conquest came the day *after* the bombing of Hiroshima.

Also, the IJA in China was weak because resources had been shifted to the defence of the home islands.

For some sense of what it would have taken to subdue the Japanese on their own home turf, consider the battle for tiny islands like Iwo Jima or Okinawa.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Okinawa

This was far more intense than the resistance the Germans put up even on their soil.

Certainly the Allies had no problems killing huge numbers of Germans if it was necessary to secure total victory - the fire bombings of Dresden and Hamburg horrifically illustrate that.

Except for the scientific community which was beginning to grasp the long term effects, the senior politicians, bureaucrats and brass regarded atomic weapons as an extension of the existing doctrines of total war and strategic bombing. They saw the atomic bomb as a more efficient way to deliver the same, massive amounts of death and destruction already being rained on German and Japanese cities.

It is only after the Allied occupation of Japan and the extensive nuclear testing of the 40s and 50s that views really began to change. The PTBT banning atmospheric testing was only signed in 1963 after 4 years of negotiation - a sign that the dangers of radioactive fallout were finally starting to be internalised by nuclear powers.

Just as the Soviets had shifted most of their heavy industries west of Urals mountains to spare it from the tender mercies of Nazis, Japan did something similar. It moved most of its important industries like Synthetic oil producing factories and others out of USAAF bomber ranges into Manchuria. Manchuria is also the place where significant amount of the Japanese agriculture was grown. Inspite of bombing Japanese to stone ages Japan still fought on and a large part of that can be attributed to what Manchuria provided to Imperial Japan. It was truly strategic depth by definition.

The myth that Japanese fought with more ferocity than the Germans fought does not tally with the figures of loss which the Germans had to undergo in 1941,in 1942 and especially in 1943 after the Kursk Fiasco. The Kursk debacle was in many ways greater in scale as compared to Stalingard in 1942 or Moscow in 1941. By the time the soviets and americans got to the germany's core the Nazis were already defeated.

But without Manchuria to back its fighting spirit, there was nothing that Japan could do. Practically its entire shipping fleet had been sunk by USN submarines. Only Manchuria, safe from the American bomber range offered it the capacity to continue the war. Once that was lost Japanese rulers saw the writing on the wall and did what was necessary. Ironic I would say. The land which Japanese invaded and occupied, i.e. Manchuria, which led to the WWII not only in Asia but also in Europe was also the place which ended the WWII.

Re: Deterrence

A few comments in no particular order:

Imperial Japan and the Axis powers also came late in the Colonial game. With the Industrial Revolution they needed captive markets also. Yes this is a Marxist take on the origins of the WWII but that does not make it incorrect.

The use of the Bomb came after a long series of atrocities:fire bombing of European cities, Pearl harbor attack with delayed declaration of war by Japan due to teleprinter slowness, Nazi death camps, the massive killings in Soveit Russia by Nazis, Japanese labor camps etc. Then we need to consider the effect of the Biblical narrative of Noah's curse on Semetic, Japhetic and Hamatic peoples. The US was and has a strong Bible reading population.

Imperial Japan and the Axis powers also came late in the Colonial game. With the Industrial Revolution they needed captive markets also. Yes this is a Marxist take on the origins of the WWII but that does not make it incorrect.