Neutering & Defanging Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

Sad times. The country that stood up against us/nato for seven decades is now forced to kowtow to a former client state for money and influence. This is a big gain for China and I'm sure many Russians will be unhappy with this development.

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

http://www.financialexpress.com/world-n ... et/482436/

Japan cabinet approves biggest defence budget

Japan cabinet approves biggest defence budget

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s cabinet today approved Japan’s biggest annual defence budget in the face of North Korea’s nuclear and missile threats and a territorial row with China. The Cabinet approved 5.13 trillion yen ($43.6 billion) in defence spending for the fiscal year starting in April, up 1.4 per cent from the initial budget for the current fiscal year.It marks the fifth straight annual increase and reflects the hawkish Abe’s attempt to build up Japan’s military, which since World War II has been constitutionally limited to self defence.Abe, who is pushing revisions to the constitution, strongly backed new security laws that took effect this year making it possible for Japanese troops fight abroad for the first time since the end of the war.Japan is on constant alert against neighbouring North Korea which has conducted two underground nuclear tests and more than 20 missile launches this year.Under the new budget, the ministry aims to beef up Japan’s ballistic missile defences, allocating funds for a new interceptor missile under joint development with the United States.Also reflected in the spending is Tokyo’s determination to defend uninhabited islets in the East China Sea — administered by Japan as the Senkakus but claimed by China as the Diaoyus.In August, Tokyo lodged more than two dozen protests through diplomatic channels claiming that Chinese coast guard vessels had repeatedly violated its territorial waters around the disputed islands.Also in August, Abe appointed Tomomi Inada, a close confidante with staunchly nationalist views, as his new defence minister. She has in the past been a frequent visitor to the controversial Yasukuni war shrine in Tokyo, which South Korea and China criticise as a symbol of Japanese militarism.Japan has been boosting defence ties with the Philippines and other Southeast Asian nations, some of which have their own disputes with Beijing in the South China Sea.The defence budget earmarks funds to dispatch extra personnel to the Philippines and Vietnam to increase gathering and sharing of information.Beijing asserts sovereignty over almost all of the South China Sea, dismissing rival partial claims from its Southeast Asian neighbours. It also opposes any intervention by Japan..

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

After Mongolian incident, Chinese daily warns India on Dalai Lama - Atul Aneja, The Hindu

The Global Times, a newspaper affiliated with the Communist Party of China (CPC), has counseled India not to leverage the Dalai Lama issue to undermine Beijing’s core interests. This in tune with an assurance that China has apparently received from Mongolia that it will no longer welcome the Dalai Lama in Ulan Bator

An op-ed in the daily on Thursday noted that the “Mongolian Foreign Minister Tsend Munkh-Orgil said Tuesday that Mongolia will not allow the Dalai Lama to visit the country, even in the name of religion, thus settling a one-month standoff between Mongolia and China.”

Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson on Wednesday also stated that the, “Chinese side sets store by the explicit statement made by the Mongolian Foreign Minister”. It added: “Tibet-related issues concern China's sovereignty and territorial integrity, and bear on China's core interests. China's position on Tibet-related issues is resolute and clear. It is hoped that the Mongolian side will learn lessons from this issue, truly respect China's core interests, honour its commitment and strive to improve China-Mongolia relations.”

The visit to Mongolia last month by Dalai Lama - described by China as a Tibetan separatist leader - has conflated with the controversial remarks by U.S. President-elect Donald Trump questioning China’s sovereignty over Taiwan.

The Global Times article sought to link the Mongolia’s subsequent problems with Beijing, following the visit to Ulan Bator, with the presence of the Dalai Lama at a function in Rashtrapati Bhavan earlier this month. “Indian President Pranab Mukherjee met with the Tibetan separatist in exile in India this month, probably as moral support to Mongolia, which mired itself in diplomatic trouble after receiving the Dalai Lama in November,” the daily observed.

It pointed out that following “countermeasures” by China including “canceling investment talks and imposing additional tolls on Mongolian cargo passing through Chinese territory, the Mongolians sought support from India “hoping that by allying with China's competitor, Beijing would be forced to give in”.

In response, “New Delhi expressed its concerns about Mongolia's well-being, and vaguely pledged to put into effect a credit line of $1 billion it promised to Mongolia in 2015. However, before India's bureaucrats could start, Ulan Bator caved in to the reality.”

The op-ed then slammed India for not recognising “the gap between its ambition and its strength”. “Sometimes, India behaves like a spoiled kid, carried away by the lofty crown of being ‘the biggest democracy in the world. India has the potential to be a great nation, but the country's vision is shortsighted.”

“India should draw some lessons from the recent interactions between Beijing and United States (US) President-elect Donald Trump over Taiwan. After putting out feelers to test China's determination to protect its essential interests, Trump has met China's restrained but pertinent countermeasures, and must have understood that China's bottom line - sovereign integrity and national unity - is untouchable. Even the US would have to think twice before it messes with China on such sensitive problems, so what makes India so confident that it could manage?”

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

Nepal to hold military exercise with China - The Hindu

Beginning a new level of bilateral military engagement, Nepal will hold its first ever joint military exercise with China on February 10, senior military officials have told Nepali media.

The focus of the military exercise, named Pratikar-1, will be on training Nepali forces in dealing with hostage scenarios involving international terror groups.

Nepal’s Chief of Army Staff General Rajendra Chhetri visited Beijing in March when both sides had resolved to strengthen military ties. Nepal has conducted exercises with India earlier.

Unconventional move

Analysts say that though the military drill with China does not violate the 1950 India-Nepal treaty of peace and friendship, it does appear unconventional.

“Nepal can conduct military exercises with other countries without violating the agreement with India, but the upcoming exercise with China is certainly unconventional and alarming as China’s definition of terrorism covers Tibetan agitators,” said Prof. S.D. Muni, a distinguished fellow at New Delhi-based Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. He believes that China is planning the military move to targeting the Tibetans.

Reports suggested that the exercise will firm up Kathmandu’s preparedness to deal with hostage situations like the one that caused large number of deaths in Dhaka’s Holey Artisan bakery in July.

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

From Twitter

Jeff M. Smith @Cold_Peace_

- Timely. Last week, 22 MPs formed India-Taiwan Parliamentary Friendship Group. Two months ago Taiwan MPs formed Parliamentary Group on Tibet.

- And on December 14 Japanese MPs formed an All Party Japanese Parliamentary Group for Tibet. Noticing a trend here?

Jeff M. Smith @Cold_Peace_

- Timely. Last week, 22 MPs formed India-Taiwan Parliamentary Friendship Group. Two months ago Taiwan MPs formed Parliamentary Group on Tibet.

- And on December 14 Japanese MPs formed an All Party Japanese Parliamentary Group for Tibet. Noticing a trend here?

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

China begins daily civil charter flights to South China Sea outpost - Straits Times

China has begun daily civilian charter flights to Woody Island in the disputed South China Sea after it approved the airport there for civil operations, state news agency Xinhua said on Thursday (Dec 22).

China claims almost all of the South China Sea, through which more than US$5 trillion (S$7.2 trillion) of maritime trade passes each year. The Philippines, Brunei, Vietnam, Malaysia and Taiwan have overlapping claims.

The first flight took off on Wednesday from Haikou, the provincial capital of China's southern island province of Hainan, and will run every day with tickets costing 1,200 yuan (S$250) one way, Xinhua said.

Woody Island, in the Paracels which are also claimed by Vietnam and Taiwan, is the seat of what China calls Sansha city that is its administrative centre for the South China Sea.

The airport, which is a joint military-civilian facility, was approved for civilian operations last Friday, Xinhua said.

"This will effectively improve the working and living conditions of civil servants and soldiers based in Sansha city," the report added.

The flights will leave Haikou airport at 8.45am and return from Woody Island at 1pm, Xinhua said.

China has been building other airfields in the South China Sea as part of a controversial land reclamation programme and in July civilian aircraft successfully carried out calibration tests on two new airports in the Spratly Islands, on Mischief Reef and Subi Reef.

China took full control of the Paracels in 1974 after a naval showdown with Vietnam.

Though China calls it a city, Sansha's permanent population is no more than a few thousand, and many of the disputed islets and reefs in the sea are uninhabited.

In February, Taiwan and US officials said China had deployed an advanced surface-to-air missile system on Woody Island.

-

sanjaykumar

- BRF Oldie

- Posts: 6726

- Joined: 16 Oct 2005 05:51

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

So the US needs to think twice before messing with China.

Or what Mr Chinaman, you gonna inundate Amreeka with eager immigrants. The yellow peril and all.

Or what Mr Chinaman, you gonna inundate Amreeka with eager immigrants. The yellow peril and all.

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

PM MODI and Dalai Lama meeting makes china upset.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q0JOt1u7UTg

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q0JOt1u7UTg

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

If this is indeed a trend then it is greatly welcome!!kmkraoind wrote:From Twitter

Jeff M. Smith @Cold_Peace_

- Timely. Last week, 22 MPs formed India-Taiwan Parliamentary Friendship Group. Two months ago Taiwan MPs formed Parliamentary Group on Tibet.

- And on December 14 Japanese MPs formed an All Party Japanese Parliamentary Group for Tibet. Noticing a trend here?

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

http://tacticalinvestor.com/tensions-es ... nce-china/

Tensions escalating in South China Sea’s; Indonesia takes stance against China

Tensions escalating in South China Sea’s; Indonesia takes stance against China

Indonesia’s Defense minister used some Harsh words in describing the intent behind the deployment of F-16’s to the Natuna Island. He said that they were deploying them to protect themselves against “thieves”, few weeks after Chinese coast guard vessels clashed an Indonesian Vessel that captured one of the illegal Chinese Vessels in the area.“Natuna is a door, if the door is not guarded then thieves will come inside,” said Ryacudu, a former army chief of staff. “There has been all this fuss because until now it has not been guarded. This is about the respect of the country.”The minister also said he was considering introducing military conscription in Natuna and other remote areas of the 17,000-island archipelago, “so if something happens people won’t be afraid and know what to do.”Aaron Connelly, a research fellow at the Lowy Institute for International Policy in Sydney, questioned if stationing F-16s in the Natuna area would act as much of a deterrent or be of use combating illegal fishing.“It looks like a show of force, but it’s a meaningless one,” he said. “Indonesia has diplomatic cards to play but it doesn’t have military ones. It’s not going to scare away the Chinese military by putting a few F-16s on Natuna. These are items that can’t be reasonably used to survey maritime activities.”Defense minister Ryacudu stated that they hoped the deal with Russia could be finalized soon to purchase 8-10 Russian Sukhoi Su-35 fighter Jets. He stated that initially they were considering buying more F-16’s from Lockheed, but we are sure after the disastrous performance of the F-35 and the incredible performance of the Su-35, Indonesia wisely changed its mind. Additionally, the Su-35 is far cheaper, just as agile (if not more) and cheaper to maintain. Russia’s superior performance in Syria has garnered it a lot of new customers.When asked if Indonesia would buy more F-16’s, he said ” no“no, we have enough already.”

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

China trying to play Bangladesh against India over Brahmaputra issue - Saibal Dasgupta, ToI

China may try to play Bangladesh against India during river water negotiations on Brahmaputra+ , which flows from the Tibetan region to northeast India on its way to Bangladesh. What is more, Beijing may try to use the Brahmaputra issue to push forward its One Belt, One Road or the Silk Road program, which India has not embraced enthusiastically.

"It is understandable that India may want to reach a deal with China over the construction of dams and the sharing of hydrological data, but Bangladesh should also enjoy similar rights to protect its own interests against India," the Global Times, an organ of the Communist Party of China, said in a commentary.

Global Times commentaries are often used by the Communist Party as a platform to spread seeds of ideas and doubts in international diplomacy, particularly in the Asian region, analysts say.

China has successfully exploited apprehensions within Nepal's political elite to create business opportunities for itself in recent months. This has been facilitated by inadequate alertness on the part of the Indian government, observers have said. It is now trying to encourage Dhaka to take up cudgels against India over sharing of waters of Brahmaputra+ . The river, called Yarlung Zangbo in China, originates from Tibet and flows down to northeastern India before entering Bangladesh.

"Just as China's dams on the Yarlung Zangbo arouse vigilance in India, India's efforts to exploit the river - which are no less ambitious than China's - have also sparked concerns downstream in Bangladesh," the paper said. The paper also advised the government to take advantage of negotiations over Brahmaputra to press for the Silk Road program. China's main success in this program is the ongoing China Pakistan Economic Corridor.

"It is necessary for China to think carefully about how it will want to resolve disputes and work to gain public support as it promotes the Belt and Road initiative throughout Asia," Global Times said adding, "Enhancing sub-regional cooperation that benefits all involved is a good choice because each interested party is able to have a say in protecting their own interests as well as in promoting regional integration".

It suggested that the Lancang-Mekong cooperation (LMC) mechanism used to resolve disputes along trans-boundary rivers covering China, Vietnam, Thailand, Loas and Cambodia should be used as a model for settling Brahmaputra issue.

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

WHY TAIWAN (STILL) COULD START WORLD WAR III

The nature of China: huge, isolated, powerful, and prone to corrective self-destruction.

China is a unique geopolitical entity. It is gigantic by both land and population: it is the largest by population and fourth largest by land. This gives it tremendous power. Geography and demography, after all, are the pillars upon which power are made.

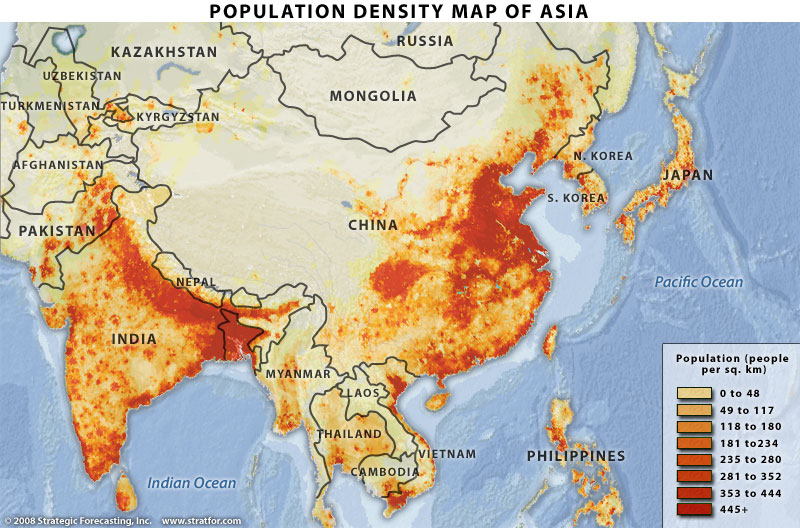

Is also, however, uniquely isolated. That doesn’t seem the case by glancing at a political map: it looks like its a big state in a crowded neighborhood. But to look at a map of Asia’s human distribution and you see the distinction.

map-population-asia-china-india

Virtually all of China’s population is crowded either along the coast or near the interior province of Chengdu. The especially ultra-crowded Shanghai-Beijing corridor is historically where Chinese elites made their homes and the backbone of Chinese society lay.

What might seem like threatening states – Russia, India, or Japan – are in fact isolated from the heart of Chinese power. India is barred by the impassable Himalayas and the sparse Tibetan plateau; Russia’s Far East is nearly empty; Japan’s highly developed population is isolated by sea and completely dependent on outsiders to supply it.

This affords it a level of powerful isolation only equalled by the United States. Unlike the U.S., however, China has had huge problems managing change.

...

The problem of remaining credible

China is at a disadvantage: it prefers to get Taiwan back, but can maintain the status quo. The Americans, on the other hand, can upset the applecart. China needs America more than the other way around, at least for now: China holds much of America’s debt, yet if tensions rose, such debt could be frozen, seized, or outright cancelled by an aggressive White House. China also needs the United States as an export market; without manufacturing, the Chinese miracle is dead on arrival.

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

The view in Beijing

Never Again Empire

The Asian region between India, Australia and Japan is a peculiar mixture of calm and risk. It isn’t chaotic like the Middle East or parts of Africa, with a landscape of failed states, fleeing refugees and unleashed terrorism. On the contrary: Prosperity and self-confidence are on the rise here in a mood of historical optimism.

Never Again Empire

A country such as India – with its huge size, atomic weapons and tradition of foreign-policy autonomy – sees itself as an independent protagonist and wouldn’t dream of entering the American or Chinese camps. It has its own problems with China that led it to strengthen its cooperation with the U.S. and its allies. But this won’t make India a U.S. treaty ally. It is definitely in favor of a multipolar world no longer led by the U.S. – but it likewise seeks a multipolar Asia not led by China.

Many Trump supporters and analysts cherish the hope that he will be the right president for a post-imperial America: Didn’t he distance himself from the hubris of the Bush years? But this is to forget that Mr. Trump is no isolationist who seeks above all to keep the U.S. out of things. He is a nationalist who wants his country to be out front and on top.

Maybe he doesn’t believe in leadership (which requires the complex management of others), but he believes in strength. "Mr. Trump wants to expand the U.S. navy, which currently numbers 274 ships," wrote two of his advisers recently. "His goal is 350 ships." That doesn’t sound like post-imperial self-restraint, rather like a new arms race in the Pacific.

But a Chinese attempt to assert its own dominance in Asia would be equally unrealistic and dangerous. Because in that case, Beijing would incur the enmity not only of the U.S. but also of a large number of its neighbors. A country like India would certainly not be willing to wage war against China in order to defend American primacy in Asia. But to prevent Chinese primacy – that is a different matter and would indeed be a possible reason for war.

There can only be security in the region between New Delhi and Hawaii through self-limitation and distribution of power. The prosperous, diverse, contradictory Asia of the 21st century would not accept the replacement of one hegemony by another. In order to avoid catastrophic conflicts, Asia must achieve the transition to a post-hegemonic state, to a system of pluralism and balance of various powers. And hopefully someday to a future based on cooperation.

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

China tests prototype of fifth-generation fighter jet - AFP

China has tested the latest version of its fifth-generation stealth fighter, state media reported on Monday, as it tries to end the West’s monopoly on the world’s most advanced warplanes.

The test comes as the nation flexes its military muscles, sending its sole aircraft carrier the Liaoning into the western Pacific in recent days to lead drills there for the first time.

The newest version of the J-31 — now renamed the FC-31 Gyrfalcon — took to the air for the first time Friday, the China Daily reported.

Better stealth capabilities

The so-called “fifth-generation” twin-engine jet is China’s answer to the U.S. F-35, the world’s most technically advanced fighter.

The new FC-31 has “better stealth capabilities, improved electronic equipment and a larger payload capacity” than the previous version which debuted in October 2012, the newspaper said, quoting aviation expert Wu Peixin.

“Changes were made to the airframe, wings and vertical tails which make it leaner, lighter and more manoeuvrable,” Mr. Wu told the paper.

The jet is manufactured by Shenyang Aircraft Corp., a subsidiary of the Aviation Industry Corp of China (AVIC). The fighter is expected to sell for around $70 million, the article said, aiming to take market share away from more expensive fourth-generation fighters like the Eurofighter Typhoon.

AVIC has said that the FC-31 will “put an end to some nations’ monopolies on the fifth-generation fighter jet”, the China Daily reported.

Weapons industry

China is aggressively moving to develop its domestic weapons industry, from drones and anti-aircraft systems to home-grown jet engines.

In the past it has been accused of copying designs from Russian fighters, and some analysts say the FC-31 bears a close resemblance to the F-35.

When completed, the FC-31 will become the country’s second fifth-generation fighter after the J-20, which put on its first public performance at the Zhuhai Air Show in November. — AFP

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

As China fumes over Agni-V, India retorts that it's not aimed at any nation - ToI

After China's negative comments today about the Agni-V test, New Delhi quickly hit back at Beijing saying the successful test not only "complied with all applicable international obligations", it was also "not aimed at any country."

"India's strategic autonomy and growing engagement contributes to strategic stability," the external affairs ministry said this evening about the test of the nuclear-capable Agni-5 intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM).

Earlier today, the Chinese foreign ministry made noises about being exceptionally concerned about Agni-V affecting "strategic balance and stability in South Asia."+ Of course, it completely ignored its own culpability in helping arm its "all-weather friend" Pakistan, a known nuclear proliferator+ .

What likely sparked Beijing's concern was the fact that Agni-V can correct South Asia's strategic balance that Beijing has actually rendered awry.

Agni V's range - 5,000 km - makes it capable of reaching the furthest northern parts of China+ as well as Europe. It's no wonder then that Hua earlier today bristled at media reports that suggested Agni-5 was targeted at China. And that's why it brought up the UN Security Council+ .

"The UN Security Council has explicit regulations on whether India can develop ballistic missiles capable of carrying nuclear weapons," Hua Chunying, spokesperson of the Chinese foreign ministry said. {What ?}

However, China too has ICBMs+ that can hit targets up to 13,000 kms. And unlike India, it isn't a part of the Missile Technology Control Regime+ , a voluntary partnership of over 30 countries created to curb the spread of unmanned delivery systems for nuclear weapons.

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

X Posted from the “Indian Foreign Policy” thread.

I wonder what the PRC Spokesperson meant when she said “The UN Security Council has explicit regulations on whether India can develop ballistic missiles capable of carrying nuclear weapons.”?:

I wonder what the PRC Spokesperson meant when she said “The UN Security Council has explicit regulations on whether India can develop ballistic missiles capable of carrying nuclear weapons.”?:

Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying's Regular Press Conference on December 27, 2016

2016/12/27

Q: Further to India's successful test of a continental ballistic missile yesterday that can reach most part of Asia and Europe, I would like to have your reaction.

A: We have noted reports on India's test fire of Agni-V ballistic missile. The UN Security Council has explicit regulations on whether India can develop ballistic missiles capable of carrying nuclear weapons. China always maintains that preserving the strategic balance and stability in South Asia is conducive to peace and prosperity of regional countries and beyond.

We also notice reports, including some from India and Japan, speculating whether India made this move to counter China. They need to ask the Indian side for their intention behind the move. On the Chinese part, China and India have reached an important consensus that the two countries are not rivals for competition but partners for cooperation as two significant developing countries and emerging economies. China is willing to work alongside regional countries including India to maintain the long-lasting peace, stability and prosperity of the region. We also hope that relevant media can report in an objective and sensible manner and do more things to contribute to the mutual trust between China and India and regional peace and stability.

Clicky

-

abhishek_sharma

- BRF Oldie

- Posts: 9664

- Joined: 19 Nov 2009 03:27

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

>> "The UN Security Council has explicit regulations on whether India can develop ballistic missiles capable of carrying nuclear weapons," Hua Chunying, spokesperson of the Chinese foreign ministry said. {What ?}

Some people on Twitter mentioned that China might be referring to resolution 1172 that was issued after nuclear tests in 1998:

Some people on Twitter mentioned that China might be referring to resolution 1172 that was issued after nuclear tests in 1998:

Calls upon India and Pakistan immediately to stop their nuclear weapon development programmes, to refrain from weaponisation or from the deployment of nuclear weapons, to cease development of ballistic missiles capable of delivering nuclear weapons and any further production of fissile material for nuclear weapons, to confirm their policies not to export equipment, materials or technology that could contribute to weapons of mass destruction or missiles capable of delivering them and to undertake appropriate commitments in that regard;

"8. Encourages all States to prevent the export of equipment, materials or technology that could in any way assist programmes in India or Pakistan for nuclear weapons or for ballistic missiles capable of delivering such weapons, and welcomes national policies adopted and declared in this respect;

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

abhishek_sharma, thanks for the explanation.

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

Beijing’s ‘technical hold’ on Jaish-e-Mohammed chief Masood Azhar expires on December 31

Beijing will *NEVER* allow Masood Azhar to be brought under the UNSC 1267 resolution. The reason is unknown why Masood is so important for China because for nine years now, China has stood firm on Masood Azhar.India is hoping for more clarity on its bid for a United Nations ban against Jaish-e-Mohammed chief Masood Azhar when China’s "technical hold" blocking the move at the UN Security Council expires on December 31.

Even as China hinted earlier this month that there is no change in its position on Islamist hardliner, India’s case has been bolstered with the National Investigation Agency’s (NIA’s) recent findings indicting Azhar in the Pathankot air force base attack on January 2.

India has yet again nudged China to stop shielding Azhar from United Nations’ sanctions, people in the know said. NIA’s chargesheet against Azhar came just 12 days before the expiry of the "technical hold", which China imposed on India’s bid to bring him under UN sanctions.

China’s inflexibility will cast a shadow on Sino-India ties which this year witnessed hiccups not only over Azhar but also over India’s NSG bid, China-Pakistan-Economic-Corridor and visas to Uyghur leaders.

The evidences collected by the NIA to indict Masood Azhar will be shared with China, persons familiar with the development said. India has yet again urged China not to extend the "technical hold" further and instead help advance the process at the United Nations to impose international sanctions on the terror mastermind based in Pakistan, officials said.

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

Does Masood have connections with Uighurs..

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

UNSC resolution 117w was Bill Clinton present to India.

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

Not Since Nixon Has a U.S. President Faced Such a Tough China Challenge

FOR MOST of the past four decades, American presidents have presumed that a “successful” China would be good for the United States. But this is no longer the case. Today, that long-standing consensus is breaking down in the face of several dynamic changes. These include China’s rapid military buildup, its unprecedentedly quick industrial and economic development, an increasingly assertive Chinese foreign policy, and new competitive pressures on the United States’ economy and fiscal health.

Even the most sanguine voices now view the U.S.-China relationship as competitive, and urge the United States to respond decisively, if carefully, especially to Beijing’s security behavior in Asia. Among Washington foreign-policy elites and a growing number of U.S. companies, China is viewed as a strategic competitor, a military threat in Asia and, ultimately, a possible adversary. Indeed, during the election campaign, Donald Trump pledged to adopt a more confrontational approach toward China, not least by threatening to impose significant tariffs on its exports to the United States. But Trump is by no means alone in this regard. Across the American political spectrum, from right to left, a new and more skeptical consensus about the rise of Chinese power is eroding the aspirational and optimistic view that prevailed for more than forty years.

It would be difficult to understate just how important and dramatic this shift could turn out to be. Eight presidents, from Richard Nixon to Barack Obama, fostered closer relations with China. Washington opened American markets and welcomed Chinese products into the United States. It encouraged U.S. firms to invest in China, sharing business practices and U.S. technologies. Bill Clinton and George W. Bush’s administrations supported China’s admission into the World Trade Organization (WTO). Over three decades, Washington enabled China’s participation in nearly every major international forum.

In the process, the United States subsumed many of its concerns about China’s Communist-led political system to its long-term interest in trying to assure a more integrated, less isolated, less autarkic China—one that joined and participated in the international system. But that was not all: by helping to enable a stronger Chinese economy, Washington also shelved, at least temporarily, some of its concerns about China’s capacity to translate butter into guns.

But while the long-standing Washington consensus about China is breaking down, it would be too simplistic to argue that the United States is now heading for a more adversarial relationship. The reality is that the Trump administration’s approach to China will be formulated against the backdrop of four swiftly changing strategic and economic conditions in Asia: the growing economic and financial integration of the region, which has shifted the relative balance of power against the United States; China’s newly assertive strategic posture; the increasingly diverse economic and social ties that now characterize American interaction with China and will make coalition building difficult, whether for more cooperation or more conflict; and the combination of eroding U.S. military advantage and protectionist trade pressures.

A Trump administration has the opportunity to adapt to these conditions. If it does, it can define an agenda with China that sets American policy onto a more strategically and politically sustainable course.

IT IS already clear that Asia is fast becoming a more integrated region—more “Asia” than “Asia-Pacific.” This means that the U.S. role will, in relative terms, become diminished over time.

This trend is structural, and thus not easily reversible. It reflects the rapid rise of Asian economies, the growth of intra-Asian trade, the restoration of old linkages between continental and maritime Asia, and the emergence of Asian market participants, companies and government financing arms as capital exporters, including to one another, not just consumers of Western capital. Taken together, this first trend will mean a smaller role for the United States in relative terms, even though U.S. trade and direct investment in Asia are rising in absolute terms.

This is a notable change, one that will make it harder for the new administration to rely on the same playbook the United States has deployed since World War II. Throughout the postwar period, but especially since the 1960s, the United States has been the principal provider of both security and economic related public goods and other benefits in Asia.

In the security realm, alliances and partnerships, solidified by the U.S.-Japan security treaty of 1960, a forward-deployed military presence and willingness to assert American power with carrier battle groups (and, when necessary, military action) have tamped down major-power war. There have been localized conflicts, of course, from Indochina to the South China Sea. But this unique U.S. role has mostly kept the peace.

In the economic realm, the United States has beaten back protectionist pressure, kept its markets open to Asian exports, led the region and the world toward liberalization of trade and investment rules, and enabled Asia’s export-led economies to power their way to prosperity.

The past two administrations, Obama and Bush, have worked to modernize America’s Asian alliances and security partnerships. But the changing U.S. economic role, especially when combined with the death of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and other tools of economic statecraft, such as American leadership of big regional trade deals and ambitious bilateral investment treaties, will reinforce the tension in U.S. policy between security and economics.

The American role as Asia’s security provider is being reinforced even as the region’s economy becomes increasingly pan-Asian. So this will deprive the Trump administration of tools that its predecessors mostly just took for granted. Asian governments will, in many ways, look to one another for trade, investment and, above all, a hedge against lingering market volatility from the 2008 financial crisis.

In short, the Trump administration will be trying to make the U.S. security posture in Asia more sustainable at precisely the moment when America’s economic profile in the region is beginning to recede.

A SECOND trend compounds this challenge: Beijing increasingly seeks to take advantage of these underlying changes in Asia. In many ways, China has begun to successfully leverage these trends to bolster its power, profile and interests.

For example, Beijing’s more assertive posture in the South and East China Seas, together with a raft of new economic initiatives, are challenging Washington’s footprint in Asia. The latter include the first true Chinese effort to build new institutions and set technical and legal standards. One illustration of this is the new multilateral Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), proposed by Beijing in 2013 and launched with fifty-seven founding members, including some of Washington’s closest allies. Another is China’s bilateral multitrillion-dollar “Belt and Road” infrastructure initiative, which aims to finance and build roads, ports, rails and power plants across Asia and beyond.

Beijing did not invent such pan-Asian initiatives. Nor did it begin to advocate them only when its self-assured president, Xi Jinping, rose to power in 2012. In fact, pan-Asianism has a decades-long pedigree, especially in Japan and Southeast Asia and also among major development banks. Nor does the construction of infrastructure by China in itself necessarily or automatically challenge U.S. interests.

But Beijing’s activism, especially against the backdrop of growing pan-Asian integration, will, in time, reinforce perceptions of U.S. retreat and Chinese advance. Thus it will challenge the Trump administration to formulate a strategically coherent and realistic response—one that gets more American skin into the game.

A THIRD trend that will affect any new administration approach is the emergence of more stakeholders in the U.S.-China relationship. This will vastly complicate the politics of building policy coalitions. Elite consensus around America’s China policy has eroded, yet it will be no easy thing to build a new one, whether for more confrontation or even more cooperation with Beijing.

That is because the number of Americans involved in the relationship with China has become more diverse and multifaceted than ever. In the 1970s, U.S. ties with Beijing were driven, in large part, by a desire to triangulate and neutralize the Soviet threat while also extricating the United States from Vietnam. Thus the core constituency for the relationship comprised strategic elites and touched geopolitical interests. From the 1980s, and especially since China’s 2001 entry into the WTO, U.S. policy has depended not just on foreign-policy elites but also Wall Street and big U.S. corporations, which have plowed some $65.8 billion in foreign direct investment stock into China while providing ballast for the relationship during periods of strategic tension. Today, however, as the economic relationship grows more diverse and decentralized, American governors and mayors, small- and medium-sized firms, farmers and ranchers, and technology developers and entrepreneurs have deep and growing stakes in the U.S.-China relationship.

The more diverse the stakeholders, the harder it will be for any U.S. administration to assemble a tightly knit political coalition around this or that overarching strategy. And in fact, this challenge will be compounded by economic change in China. As Beijing moves to deploy an even larger share of its $3 trillion in foreign-exchange reserves (and billions more on corporate balance sheets) into direct investments overseas, American states, cities and businesses have begun to clamor for a share. Vice President–elect Mike Pence’s Indiana offers just one example: the state has both lost jobs to and gained jobs from China. Some factories have closed and moved operations to China, yet the state has also attracted job-creating green field investment, such as Nanshan Group’s $160 million aluminum extrusion operation in West Lafayette, which employs hundreds. China is one of Indiana’s top overseas markets, with $2.1 billion in exports in 2015.

This complex set of economic interests is now multiplied in state after state. In turn, even as trade competition with China mushrooms among the established players, it is creating at least some new interest groups, warier of economic confrontation between Beijing and Washington.

Similarly, as China deploys, on a massive scale, commercial technologies, with which medium-sized U.S. firms have a competitive advantage, exports to China will be integral to the growth strategies of midcap firms, not just the large U.S. multinationals that have dominated U.S.-China economic relations to date.

A FINAL trend involves growing constraints on U.S. foreign- and economic-policy activism. Sadly, these may handicap the United States in Asia just as Washington needs greater leverage to balance the rise of Chinese power.

The United States needs new military and economic tools to bolster its footprint. Yet polls consistently show that the public has grown wearier of such engagement. The 2016 presidential campaign, where both major-party nominees came out against the TPP, demonstrated that traditional tools, such as large-scale trade deals, are under intense pressure.

The good news is that the Trump administration and congressional leaders seem likely to end the defense-budget sequester and pursue tax, fiscal and competitiveness reforms that would strengthen the U.S. hand in Asia. Though TPP is now dead, bilateral trade deals apparently remain on the table.

Still, the need for major new naval- and force-projection investments, as well as an overhaul of U.S. economic and competitiveness policies, will be no simple task for the president and Congress.

In sum, the United States must make its China policy in the period ahead amid rapidly changing conditions in Asia and with a more constrained set of tools for strategic and economic statecraft.

AGAINST THIS backdrop, the new president and his administration must meet some specific challenges with China. For one, it has long been presumed that economic integration between the two countries would mitigate security competition. Yet to put it bluntly, that does not seem to be happening, and, if anything, military tensions and competition are actually intensifying. The region’s story now resembles a “Tale of Two Asias,” with economics and security colliding, not running in parallel—the U.S.-China relationship is a microcosm of this debilitating dynamic.

Indeed, the United States and China have never been so economically integrated. Two-way trade now exceeds $600 billion. China is America’s fastest-growing export market; and in agriculture, for instance, exports to China have grown 200 percent over the past decade, reaching $20.2 billion in U.S. farm and food exports in 2015.

But despite this deepening integration, security tensions have escalated, with the risks of military conflict now more real than at perhaps any time since the 1950s.

At the simplest level, the problem involves choices and policies in the South China Sea, cyber-related tensions and so on. It also touches China’s deteriorating relationships with three of America’s five Pacific allies—Japan, South Korea and Australia. Where Beijing has sought to firewall U.S.-China relations from, say, China-Japan relations, its pressure on American allies is bleeding into relations with Washington too.

And yet a deeper problem exacerbates these day-to-day security tensions: Washington and Beijing have developed clashing security concepts in Asia. As a result, they are talking past each other about what has caused tension in the region, finger pointing at one another, and pursuing contradictory approaches.

This has reduced the two sides to trying to avoid accidents and minimize escalation risk, while fatalistically accepting the sharpening of competition. Just take the South China Sea: Beijing asserts its national maritime rights and interests, while Washington talks mostly about international norms, rules and law. The two governments disagree, fundamentally, on how to interpret some important aspects of international law. And the United States perceives that China acts as if its interests trump international law. With such irreconcilable views, the two sides are talking past each other, as the sea becomes the locus of a full-contact spat between Washington and Beijing.

For Washington, this will require a series of systematic approaches in the near term: in the South China Sea, firm adherence to principles of international law; a willingness to operate its fleet and aircraft where the law permits; maintenance (or new building) of a naval capacity to so operate; routine but discreet, as opposed to erratic yet showy, freedom-of-navigation operations, directed at sending consistent messages to China and its neighbors rather than public relations; assistance to allies and partners with domain awareness; and a continuing effort with Beijing to mitigate the risk of accidents.

It will also require substantial diplomatic effort, for instance, by encouraging the non-China claimants in Southeast Asia to settle their claims with one another, in part to strengthen their collective hand with Beijing.

Security competition with China will be a fact of life for the new president. It cannot simply be wished away. But Washington also needs to be more vigilant about distinguishing its vital interests from those that are more peripheral—and this will be particularly true as it manages diverse security partnerships around Asia.

Of course, the economic relationship will not be so easy either, and not just because President-elect Trump promises a toughened policy. China and the United States have become centerpieces in wider strategic and economic debates that will play out, ultimately, in each side’s domestic politics and are bigger than bilateral relations per se. In the United States, these include the future of American manufacturing, competitiveness and innovation. In China, they include the pace and scope of economic rebalancing, and whether (and when) to knuckle under to international pressure on China’s industrial, regulatory and currency policies.

Put simply, while the United States and China are interdependent, a growing number of stakeholders on both sides find that reality thoroughly disquieting.

Chinese industrial policy starkly illustrates this: while some Americans, including Trump, have continued to emphasize China’s currency policies, that issue is fading as Beijing has sustained a gradual appreciation of the yuan. Instead, China’s industrial policies will rise to the fore, especially its use of regulatory tools to restrict foreign competition and support the growth of Chinese national champion firms, both state-owned and private. And those tensions will be tougher still because they strike at the core of each country’s economic competitiveness.

China’s ability to compete with U.S. firms has improved faster in some areas than many had anticipated. From high-speed rail to nuclear power plants, China’s capacity to digest foreign technology, reengineer it to Chinese specifications and then produce (but as a lower-cost competitor) has unnerved a host of foreign companies, who now question the wisdom of transferring technology to China. The underlying fear is that if China can quickly produce substitutable (but cheaper) products, then foreign firms will be marginalized.

Even with a tougher U.S. posture, it will be difficult to coordinate actions and responses, as the complexities of this Chinese challenge vary across sectors and affect distinct firms differently.

The good news is that while economic integration has not alleviated U.S.-China security competition, the economic relationship, although contentious, is changing from the heavily trade-dominated relationship that was the focus of Trump’s campaign to one that also includes substantial direct investment.

Unlike trade, which involves buying and selling at the border, or bond holdings, which can be bought or sold through a quick paper transaction, direct investments involve people, plants and other assets. They are, in that sense, a vote of confidence in another country’s economic system since they take time both to establish and unwind. And they create more direct ties between two economies.

The growing role of investment, then, will give the two sides another bite at the apple—a chance to test if a more direct form of economic linkage, especially if it creates jobs in the United States, can build a more enduring foundation.

The U.S. debate about investment is likely to grow contentious, in part, because some sectors in the United States that are open to Chinese firms are not open in a reciprocal way to American investment there. This is fueling debates about a need for greater reciprocity. Moreover, the murky governance of China’s state-owned enterprises makes their acquisition of publicly traded U.S. companies both sensitive and, in some cases, deeply problematic.

What is needed is a serious process that shifts the U.S. emphasis from defense to offense—from reactively lawyering specific trade cases and debating this-or-that tariff to a systematic and proactive effort to align with Chinese economic reformers who can promote change within, and extract concessions from, their system.

In recent years, Washington has used negotiations over a potential bilateral investment treaty (BIT) as precisely such a lever to open up closed sectors of the Chinese economy. A BIT remains a useful tool but, with the Senate unlikely to approve a treaty, a more realistic step in the administration’s first months would be to begin an intensive bilateral negotiation process that offers more in exchange for real reform and opening, but would exact real consequences for a failure to move.

In that way, punishments and consequences would be a function of failed negotiation, not just of unilateral action. It would establish a firmer footing for bargaining between the two governments. And Washington could logically focus such an effort on market access in sectors where the United States is most competitive—for instance, services, healthcare and technology. Chinese economic reformers do not always welcome foreign competition, but they do certainly understand the importance of competition in the economy generally. And this is especially important because some reforms are being rolled back or are proceeding too slowly. Put bluntly, statism is advancing in too many areas of China’s economy. By using a negotiation to link market access to competition policy, U.S. negotiators could help invest Chinese reformers in a renewed push to foster it. Ultimately, more competition would benefit Chinese private-sector firms, help reformers break down state-led oligopolies, expose state firms to the discipline of the market, help make the market “decisive” in China’s economy (a goal the Chinese Communist Party itself set at a November 2013 plenum) and, ultimately, benefit both countries.

A SECOND challenge Trump will face is that even when Beijing and Washington share interests, these are, too often, overly general in nature—“peace,” “stability,” “security,” “nonprovocation” and so on. Often, the two sides fall flat when trying to turn their common interests into complementary policies.

The United States and China actually have a long history of cooperating around the world, including in sensitive regions around China’s periphery.

Consider Afghanistan. Recent strains belie the degree to which Beijing and Washington worked jointly to defeat the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s. The United States encouraged Chinese support for the Afghan mujahideen, and the two countries cooperated in other novel ways during the conflict.

Today, by contrast, the two capitals are often at loggerheads in such places. For instance, before Myanmar’s political transition to Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s government, U.S. officials argued that Beijing’s policies only helped to bolster the ruling junta. Likewise, Americans argue that Chinese trade and investment policies shield North Korea from the effects of the very international sanctions Beijing voted for.

For their part, Chinese officials view U.S. policies in some of these countries as naïve at best, destabilizing at worst. In Central Asia, for example, while serving as deputy assistant secretary of state for the region in 2006 and 2007, I heard Chinese officials argue ad infinitum that U.S. actions to promote political reform would ultimately “destabilize” these countries.

Does coordination really have to be so hard? The challenge for Trump’s administration is threefold.

First, the two countries need to better align their threat assessments. So for all that Washington may have security tensions with China, what is needed is a more intensive strategic and contingency planning discussion. Beijing, quite simply, does not share American assessments of the scope and urgency of some important threats. And China’s leaders, even when they do sense a challenge to “stability,” are more relaxed about them than Americans.

This is true of Pakistan, where Beijing tends to trust the military’s instincts implicitly. It is true of Iran. And it is true of North Korea. Few Chinese believe Kim Jong-un’s regime will collapse. Beijing will not push Pyongyang over the precipice and retains hope for a managed transition toward Chinese-style reform.

Second, even when Beijing shares Washington’s sense of threat, countervailing interests can obstruct cooperation. In Afghanistan, China has certainly shared America’s core interest in a stable Afghan state that does not harbor, nurture or export terrorism. But Chinese decisionmakers were never comfortable in the 2000s with NATO access arrangements across China’s western border in pursuit of this objective, much less enhanced U.S. strategic coordination with neighbors that have difficult relations with Beijing.

Third, the administration needs to overcome the contradictory U.S. and Chinese ranking of shared objectives. In North Korea, both value stability and denuclearization, but China values stability much more, while the United States has been prepared to risk some stability to achieve denuclearization.

To deal with these obstacles, Washington and Beijing badly need a track record of concrete successes in places where shared strategic interests exist but are often too abstract.

Doing so will not require joint projects and actions, merely complementary ones. Take, for instance, counternarcotics in Afghanistan and Central Asia: China works bilaterally and through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization; the United States works mostly bilaterally through security assistance and capacity building. Washington and Beijing do not need joint efforts to pursue their shared goal, just to coordinate areas of focus, direct their financial assistance at similar drugs-related goals, and build complementary capacity while maintaining separate efforts.

ULTIMATELY, THE global arena, not East Asia, is likely to be more conducive to near-term cooperation. And while global cooperation cannot mitigate security tensions in the Pacific, it will further enlarge the field for action.

To deploy an American baseball metaphor, such cooperation does not always mean the two sides should “swing for the fences.” Often, the United States has sought cooperation with China around the world, but failed. By working on more peripheral issues, the two countries have a chance to work over time toward more significant strategic ones.

In particular, better coordinating some international economic policies will likely prove easier than coordinating security policies. One example would be to encourage even more coordination between the international financial institutions and the new China-backed Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Even if the United States does not join the AIIB, it can encourage and promote cofinancing of projects via its voting weight and project support to more established structures. This would provide the United States and China with some multilateral “cover,” and thus prove easier than coordinating bilaterally.

Another example would be to jointly shape investment standards in other countries and regions, like Africa. China’s arrival as a trader, investor, lender and builder has dramatically changed the economic environment around the world because, while Chinese investors are not oblivious to the challenges of doing business in, say, Papua New Guinea or Niger, they have taken on risks where American, Japanese and European firms have not. And China has already displaced other, more traditional partners across an array of sectors.

Chinese strategies are hardly uniform. Nor have they proved to be uniformly successful. Resources for infrastructure deals have benefited Chinese construction, telecommunications and hydropower companies. But Chinese oil and mining companies have failed to dominate Africa’s extractive industries, for example. And significant infrastructure investments in mineral-rich countries have not given Chinese firms a preferential position.

Many American analysts take for granted that Chinese companies can bear more risk, or that Beijing will underwrite the kind of risks that other governments shy away from. But as China’s reach grows, its economic incentive to revisit these practices may expand, not least to protect its own investments. Chinese companies no longer operate alone in many places, and are seeking partnerships—first to acquire technology, second to share risk, and third to connect to new skills and industry practices. The Chinese even surprised their State Department counterparts in a mid-2000s round of policy-planning discussions by asking about the good-governance provisions in President Bush’s Millennium Challenge development fund.

Chinese firms, backed by state loans, face growing constraints in countries that have stringent local content rules. So there are limits to China’s traditional approach: The weaker the state, the more appealing is China’s model of trading loans and infrastructure for resources. But the stronger the state, the more wary countries are likely to be of falling into a debilitating trap of dependence.

And that opens up some potential space for the United States and China (and third parties) to work jointly on standards, investment models and other issues in partnership.

THE BOTTOM line is that President Trump will face a tougher challenge with Beijing than have his eight predecessors since the 1972 Nixon opening. China is now weightier, more influential around the world, better able to resist or retaliate against U.S. pressure, and has more tools of economic statecraft and military power than ever before.

This means that Washington needs to move from reactive to activist in its approach to both China and Asia. After all, for much of the last decade—and with the exception of the now-shelved TPP—the United States has too often found itself acting in response to a Chinese initiative.

The AIIB is just one example. The United States offered no distinctively “American” model of infrastructure finance for Asia, failed to complete governance reforms in the existing international financial institutions, chose to forego the opportunity to shape the bank early on, and then discouraged its allies and others from joining. The result was that Washington was left responding to a Chinese initiative (and ended up isolated from nearly all of its allies) rather than setting the action agenda itself. Likewise in the South China Sea: the United States increasingly seems to conduct freedom-of-navigation operations in response to Chinese island building or other actions, rather than as a function of strategy.

American interests in the Pacific have been consistent for more than a century: open markets; open regionalism; freedom of navigation; no exclusionary blocs or dominant regional hegemons that might exclude the United States; support for political and economic openness; and, in the postwar period, support for allies.

It would be the height of irony if the United States, Asia’s principal champion of openness since the nineteenth century, begins to close itself off from the region. If the new administration pursues tough-minded, productive relations with China, but anchors it very firmly within this larger context of strategy in Asia, then it will be off to a realistic start.

Evan A. Feigenbaum is vice chairman of the Paulson Institute at the University of Chicago. During the George W. Bush administration, he served as deputy assistant secretary of state for South Asia, deputy assistant secretary of state for Central Asia, and on the secretary of state’s policy planning staff with principal responsibility for East Asia and the Pacific.

Image: Forbidden City. Flickr/Creative Commons/Yiannis Theologos Michellis

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

X-post:

sum wrote:Was this ever posted here?

A long read on actual capabilities of Chinese and Indian intel on each other:

Why India And China Must Strengthen Their Espionage Capabilities

China’s spy service network is widespread with hundreds of thousands of staff in several different agencies and more outside the intelligence services. The data provided is mostly useless, and if useful, often ignored. India’s spy services are smaller but it has some outstanding agents who carry out the bulk of the useful work. These exceptional agents have, by themselves, justified the budgets of the entire intelligence network by serving India’s national interests at critical moments. But India does not have an effective team focussed on China. Meanwhile, China has not devoted resources to India – its government accepts that it lacks detailed intelligence on India but believes there is no need to assign more resources.

China invests more in espionage than India, but its effectiveness is overstated in Western media and by foreign militaries. Much of the intelligence obtained by Chinese spying hits the pockets of foreign companies rather than directly helping China’s defence strategy, but some is of national security significance such as the collection of the US government personnel data in May 2015.PLA Intelligence is expected to track the order of battle of the Indian Army, its strategies, location, and profiles of commanders. This is not difficult since much information is in public domain but the difficulty lies in getting “first and more” – getting the information before it becomes public, and getting more information than becomes public. However, PLA Intelligence is not bothering to achieve “first and more”, believing that the Indian military’s secrecy is so lax that little of importance could avoid becoming public knowledge.

The task of PLA Intelligence also covers terrain assessment, identification of command/control centres, plotting vulnerable areas and points, profiling equipment and counter-intelligence. This kind of information cannot only come from public sources, so the PLA has Military Reconnaissance Units (MRUs) in border areas. SIGINT is particularly important because HUMINT operations are so difficult against India.Recent cases of Chinese espionage in India show just how difficult it is. Pema Tsering was arrested in 2013 in Dharamsala, the Dalai Lama’s base. He was an ineffective agent. Tsering had been jailed while serving in the Chinese armed forces and was released by the Chinese when he agreed to spy on the Dalai Lama’s group, but he was then recruited and paid by the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), India’s main intelligence agency. Wang Qing was arrested in Dimapur in 2011. She flew to Kolkata from Kunming on a tourist visa as an executive of a Chinese timber company (she should have been on a business visa – even the cover was executed clumsily) and allegedly held a meeting with a Naga insurgent leader. She was deported from India.The honey-trap technique is commonly used by Chinese intelligence, whether from the MSS or from the PLA. The encounter must be made to appear genuine, which increases in difficulty the more important the target. One method of reducing this difficulty is by turning a party to a genuine liaison into an amateur agent. This is easier than it sounds, since the purpose of honey-trapping is usually to provide a one-off opportunity to bug an apartment or to photograph documents. RAW has been the victim of such operations: its low point in China was in 2008 when its station chief, Uma Mishra, was recalled for a bungled investigation into a honey-trap case involving one of her staffers.

The Embassy reported that the staffer had been marked by two different Chinese agents and had his apartment bugged. These Chinese HUMINT projects have yielded little and are difficult to arrange. Cyber-espionage is easier. China is indulging in large scale cyber espionage using an army of hackers, drawn from military, intelligence and business. The PLA’s organisation is usually considered stove-piped, but in cyber-warfare it is not. It now links all service branches via a common ICT platform capable of being accessed at many command levels and has created new departments to service its cyber warfare agenda.RAW does not have the adequate number of agents who are not of Indian ethnicity (just as China has few non-Han agents). It has scant cover for operations in China since so few Indian companies are active in China. The exception is the Tibetan ethnic group. According to the Indian press, China press-gangs Tibetan refugees in Nepal to spy on India, and it is true that a few ethnic Tibetans have been caught spying for China (such as Pema Tsering). But there are far more engaged in spying on China. There are over 100,000 Tibetans in India; they are politically motivated, and ethnically and linguistically they blend in with Chinese Tibetans. They are rarely caught.

One agent gave an account of his activities to Indian media. His ethnicity is unknown –a Sikh-sounding name ‘Raghav Singh’ was given but this is not his real name – and he described observing Chinese military activity in October 2012. He and his colleague claimed to have been shot at by the PLA and described escaping through a pine forest, where they were lost for three days before reaching base camp “with a great piece of intelligence”. Ethnic Tibetans from the region close to the Chinese border are employed by Indian intelligence.Apart from the lack of detailed intelligence on China’s political attitudes and scant ground intelligence, there are gaps in India’s knowledge of China’s capability in the border areas. For example, India is unsure of the locations of DF-21 missiles. The Indian government also often exaggerates the threat from China. In 2005, the Indian government conceded that its own reports of China turning the Coco Islands in Burma into a naval base were incorrect. And China’s huge construction projects in Gilgit-Baltistan (a region of Kashmir) need to be watched in greater details.Yet China is a long way from having this capability. One India expert in China pointed out that Chinese intelligence has very few India specialists. They focus on Japan and the US, and then Europe. He himself does not speak Hindi, and yet is one of China’s premier experts on India – making him a living example of the lack of specialism. Relying on military intelligence alone is no substitute for a functional and effective civilian intelligence networks.

The two countries are thus in a difficult situation; their size and proximity make it inevitable and necessary that they compete, cooperate, and share, but their ignorance has led them to miss opportunities to profit from each other’s experience, wealth and talents.

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

Yes, it is rather sad that India (and the chinis) rely mainly on western reports on its biggest neighbor.

In contrast, the US has massive resources on China both from Wall Street and in Washington as well as academia (Harvard and many leading American universities run China Studies programs.)

From the finance end, China knowledge is exceptional with two of the previous three being China experts in Henry Paulson and Timothy Geithner. Geithner, and I believe Paulson as well, are Mandarin speakers.

We have very little in the way of first class China programs and experts except for Arvind Subramanian, chief economic advisor of the GOI. Arvind though is a China expert because he is American as well. He was the first Wall Street economist to calculate that China was a bigger economy and market than the US and that US firms should plan accordingly.

In contrast, the US has massive resources on China both from Wall Street and in Washington as well as academia (Harvard and many leading American universities run China Studies programs.)

From the finance end, China knowledge is exceptional with two of the previous three being China experts in Henry Paulson and Timothy Geithner. Geithner, and I believe Paulson as well, are Mandarin speakers.

We have very little in the way of first class China programs and experts except for Arvind Subramanian, chief economic advisor of the GOI. Arvind though is a China expert because he is American as well. He was the first Wall Street economist to calculate that China was a bigger economy and market than the US and that US firms should plan accordingly.

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

Pakistan inaugurates nuclear plant built with Chinese aid - AP

Pakistan Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif on Wednesday inaugurated a 340 MW nuclear power plant built with Chinese aid, the third of four such projects aimed at addressing long-time energy shortages.

In a televised speech Wednesday, Mr. Sharif vowed to eliminate power cuts by 2018, when his five-year term expires, and set the ambitious goal of generating 8,800 MW of power by 2030.

The government has not provided figures on the cost of the plants or the Chinese contribution, saying only that Beijing has provided technical support and that Chinese engineers have worked on the projects.

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

http://warontherocks.com/2016/12/it-is- ... china-sea/

IT IS HIGH TIME TO OUTMANEUVER BEIJING IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA

IT IS HIGH TIME TO OUTMANEUVER BEIJING IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA

art of the reason is the way that China has asserted its sovereignty over some 80 percent of this strategic waterway. The South China Sea is a stretch of water that carries more than half of the world’s merchant tonnage and serves as an important transit route for the militaries of the United States and many of its allies and friends. During the last five years, Beijing’s footprint has expanded markedly with the dredging-up of new islands and the construction of facilities for surveillance, anti-air, anti-shipping, and strike forces. Beijing’s campaign has been cleverly conducted via a succession of modest incremental steps, each of which has fallen below the threshold that would trigger a forceful Western response. As a result, Beijing now has significant facilities on 12 islands in the South China Sea and operates by far the largest military, coastguard, and maritime militia presence in the region.Amongst the military capabilities that the Chinese appear to be installing on these artificial islands are surveillance and intelligence gathering facilities, long-range anti-aircraft and anti-ship missile installations, and numerous missile and gun point-defense systems. Three of the islands in the Spratly group, towards of the middle of the South China Sea, now possess 10,000 foot airfields that are more than adequate to handle Boeing 747 operations. Hardened revetments to house 24 fighter-bomber aircraft are nearing completion on these three islands together with what appears to be extensive maintenance and storage facilities for fuel and other supplies. Aircraft operating from these facilities could range as far as the Andaman Sea, Northern Australia, and Guam.At present, innocent passage, especially by commercial vessels, is being respected. However, Beijing is making clear that the terms and conditions of foreign activity, even by other littoral states, will be determined and enforced by China. Relevant Chinese authorities have signalled that Beijing is considering the declaration of an air defense identification zone (ADIZ) over the entire South China Sea. Military facilities now nearing completion will permit Chinese forces to enforce any such declaration with fighter intercepts of non-complying aircraft.When confronted by China’s territorial and military expansion in the South China Sea, allied leaders have almost always responded by repeating a standard mantra: We have a strong interest in free sea and air passage, we have no national claims to territories in the area, and we call on all parties to exercise restraint and resolve competing claims in accordance with international law. In token support of these interests, allied ships and aircraft have periodically transited the region, though they have rarely challenged China’s territorial claims directly. This response has clearly failed to deter Beijing’s territorial expansion.

Why has the approach of the United States and its close allies been so timid and ineffectual? There have been several factors at play.Second, the level of importance accorded to the strategic future of the South China Sea varies greatly between allied and partner capitals. The general view in Washington is that the South China Sea is important but not vital. It is simply one of many troubled areas with which the United States must deal. In Tokyo, Seoul, and Canberra, the South China Sea is far more important because of its intrinsic strategic value and critical importance to their close partners who are maritime members of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN). For the littoral states of the South China Sea, the strategic balance and effective sovereignty of the region is critical for their future security and economic well-being. These differences in priority between the Western Pacific allies and their friends are placing strains on long-standing security relationships.A third serious constraint has been imposed by the hub-and-spokes alliance model that has been in place in the Western Pacific since the 1950s. Cross-alliance (outer wheel) cooperation and combined security planning is not well-developed amongst the Western Pacific allies. While some progress has been made in recent years in strengthening operational coordination between Japan, Australia, South Korea and some partner countries in Southeast Asia, it is still limited and much of it is not routine. Washington has certainly encouraged closer cross-alliance cooperation but and it has a long way to go to approach the type of combined security planning that is habitual in Europe. . In consequence, timely, efficient, and effective alliance cooperation in response to Beijing’s operations in the South China Sea has not been straightforward.The success of Beijing’s information operations in Western countries is a seventh factor in accounting for the Western allies’ timidity over Chinese behavior in the South China Sea. These operations have been assisted by the Chinese acquisition of media enterprises in Western countries as well as the courting of key decision-makers, journalists, and academics through fully paid visits to China; the contribution of substantial funds to political parties; the establishment of pro-Beijing associations of many types, including Confucius Institutes in universities; the regular insertion of Chinese produced supplements in metropolitan newspapers; and the organization of periodic “patriotic” demonstrations, concerts, and other events by Chinese embassies, consulates, and other pro-Beijing entities. Cyber and intelligence operations have been used to reinforce key messages, recruit Chinese intelligence agents and “agents of influence,” and to intimidate, coerce, and deter allied counter-actions.

In reality, the first key interest of the allies is ensuring that China does not dominate the South China Sea to the extent that it can unilaterally determine the regional order and dictate the level of sovereignty to be enjoyed by the littoral states. A second key interest of the allies is limiting the potential for China’s acquisitive actions in the South China Sea to set a precedent for further, more aggressive illegal actions by Beijing in either the short or the long term. A third key allied interest is ensuring that China’s serious breaches of the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, its dismissal of the findings of the Tribunal of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, and its direct challenge to international law are not repeated.

Given Beijing’s actions during the last five years, there is a need to progress beyond the so-called “pivot” and “rebalancing” to a more thoroughgoing military engagement with the region that might be called the Regional Security Partnership Program. The primary goals of such a program would be to demonstrate continuing allied military superiority in the theater, deter further Chinese adventurism, and reinforce the confidence of regional allies and partners in the reliability of their Western partners so that they feel able to staunchly resist any attempted Chinese coercion.The most effective allied strategy will be innovative and asymmetric. Just because Beijing has focused its most assertive actions in the South China and East China Seas in recent years using various forms of military, coast guard, maritime militia, and political warfare assets, it does not mean that the allies should counter by focusing all of their efforts in those theaters and employing those same modes. To the contrary, the most effective allied options are likely to focus on applying several types of pressure against the Chinese leadership’s primary weaknesses in whatever theater that is appropriate. ( POK Balochistan being Neck and Mush of PRC shenanigans)