India's Polar Engagement: News & Discussion

India's Polar Engagement: News & Discussion

The Sino-Russian partnership has expanded not only qualitatively, but also geographically with some of their interaction reaching the Arctic Circle. In April 2019, Russia announced plans to connect the Northern Sea Route, along which Moscow plans to begin year-round navigation in 2022-2023 with China’s Maritime Silk Road. Use of the NSR could pose significant advantages in terms of shipping times. According to a 2018 study published by The Economic Journal, commercial use of the NSR could represent a reduction of average shipping times by about one-third compared to its southern counterpart. In practical terms, shipping from China to the United Kingdom would decrease by 25% compared to the Suez Canal route, and from China to the Netherlands by 23%, according to the study, which estimated that overall trade cost reductions brought about by this more efficient route would increase trade flows by an average of 10%. According to the article, use of the NSR could decrease transportation costs between China and various European countries (e.g. Germany, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands) by upwards of 20%. The authors predicted that by 2030, some 13.4% of Chinese trade would be re-routed through the NSR.

Moscow has also signaled wariness in recent years with respect to Beijing’s growing Arctic ambitions. In 2007, China first applied to become an observer of the Arctic Council, the leading intergovernmental body promoting Arctic cooperation. Comprising eight permanent members, all of which have territories within the Arctic—Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States—the Arctic Council envisions itself as the region's collective body of stewards, charged with overseeing the land, waters and people of the region. At the time of China’s initial application, according to the Arctic Institute, Moscow displayed resistance to what it viewed as the Council's unnecessary internationalization, as its Nordic partners on the Council pushed for the inclusion of any state that could make a compelling case for its observer status. Beijing succeeded in its bid to join the Council as a non-Arctic observer state in 2013. Two years later, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov made clear that Chinese-Russian cooperation in the region was purely bilateral and had no bearing on the Council’s governance affairs. "China is an observer in the Arctic Council. China seems to have favorable prospects, because it has appropriate resources, technologies and scientific potential. But our Arctic cooperation with China should not boil down to the Arctic Council. Russia’s Arctic zone is the area where we can work on a bilateral basis with many partners. Of course, China is one of the priority partners," he said in 2015. Then in 2018, the Chinese government released a white paper detailing the policy implications of its status as a so-called “Near-Arctic State.” In the paper, China argued that due to climate change, the Arctic was no longer the concern of the region’s states alone. “The Arctic situation now goes beyond its original inter-Arctic States or regional nature, having a vital bearing on the interests of States outside the region and the interests of the international community as a whole, as well as on the survival, the development and the shared future for mankind.” The paper went on to define a near-Arctic state as “one of the continental States that are closest to the Arctic Circle,” arguing that shifting Arctic conditions have a direct impact on China’s environment, and thus on its economic health. According to the paper, the consequences of this self-designated status are sweeping. “China’s policy goals on the Arctic are: to understand, protect, develop and participate in the governance of the Arctic, so as to safeguard the common interests of all countries and the international community in the Arctic, and promote sustainable development of the Arctic.”

In comments delivered in May 2019, the US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo responded in no uncertain terms. “Beijing claims to be a ‘Near-Arctic State,’ yet the shortest distance between China and the Arctic is 900 miles. There are only Arctic States and Non-Arctic States. No third category exists, and claiming otherwise entitles China to exactly nothing,” he said. Russia’s top Arctic official, Nikolai Korchunov, made the surprise move in June 2020 of effectively siding with Washington’s then-top diplomat. "Russia is not interested in delegating its rights to other states," he said, as quoted by TASS. “In this respect it is impossible to disagree with [Pompeo’s] statement made in May 2019 that there are two groups of countries—Arctic and non-Arctic. He said so in relation to China, which positioned itself as a near-Arctic state. We disagree with this." At the core of all this geopolitical posturing is the fact that warming Arctic temperatures open up a bounty of natural resources. The Arctic may contain up to 90 billion barrels of oil and 47 trillion cubic meters of natural gas, Russia's potential shares of which amount to 48 billion barrels and 43 trillion cubic meters, respectively, and some $1 trillion worth of rare earth metals.

Moscow has also signaled wariness in recent years with respect to Beijing’s growing Arctic ambitions. In 2007, China first applied to become an observer of the Arctic Council, the leading intergovernmental body promoting Arctic cooperation. Comprising eight permanent members, all of which have territories within the Arctic—Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States—the Arctic Council envisions itself as the region's collective body of stewards, charged with overseeing the land, waters and people of the region. At the time of China’s initial application, according to the Arctic Institute, Moscow displayed resistance to what it viewed as the Council's unnecessary internationalization, as its Nordic partners on the Council pushed for the inclusion of any state that could make a compelling case for its observer status. Beijing succeeded in its bid to join the Council as a non-Arctic observer state in 2013. Two years later, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov made clear that Chinese-Russian cooperation in the region was purely bilateral and had no bearing on the Council’s governance affairs. "China is an observer in the Arctic Council. China seems to have favorable prospects, because it has appropriate resources, technologies and scientific potential. But our Arctic cooperation with China should not boil down to the Arctic Council. Russia’s Arctic zone is the area where we can work on a bilateral basis with many partners. Of course, China is one of the priority partners," he said in 2015. Then in 2018, the Chinese government released a white paper detailing the policy implications of its status as a so-called “Near-Arctic State.” In the paper, China argued that due to climate change, the Arctic was no longer the concern of the region’s states alone. “The Arctic situation now goes beyond its original inter-Arctic States or regional nature, having a vital bearing on the interests of States outside the region and the interests of the international community as a whole, as well as on the survival, the development and the shared future for mankind.” The paper went on to define a near-Arctic state as “one of the continental States that are closest to the Arctic Circle,” arguing that shifting Arctic conditions have a direct impact on China’s environment, and thus on its economic health. According to the paper, the consequences of this self-designated status are sweeping. “China’s policy goals on the Arctic are: to understand, protect, develop and participate in the governance of the Arctic, so as to safeguard the common interests of all countries and the international community in the Arctic, and promote sustainable development of the Arctic.”

In comments delivered in May 2019, the US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo responded in no uncertain terms. “Beijing claims to be a ‘Near-Arctic State,’ yet the shortest distance between China and the Arctic is 900 miles. There are only Arctic States and Non-Arctic States. No third category exists, and claiming otherwise entitles China to exactly nothing,” he said. Russia’s top Arctic official, Nikolai Korchunov, made the surprise move in June 2020 of effectively siding with Washington’s then-top diplomat. "Russia is not interested in delegating its rights to other states," he said, as quoted by TASS. “In this respect it is impossible to disagree with [Pompeo’s] statement made in May 2019 that there are two groups of countries—Arctic and non-Arctic. He said so in relation to China, which positioned itself as a near-Arctic state. We disagree with this." At the core of all this geopolitical posturing is the fact that warming Arctic temperatures open up a bounty of natural resources. The Arctic may contain up to 90 billion barrels of oil and 47 trillion cubic meters of natural gas, Russia's potential shares of which amount to 48 billion barrels and 43 trillion cubic meters, respectively, and some $1 trillion worth of rare earth metals.

Re: India's Polar Engagement: News & Discussion

Place Holder 2

Re: India's Polar Engagement: News & Discussion

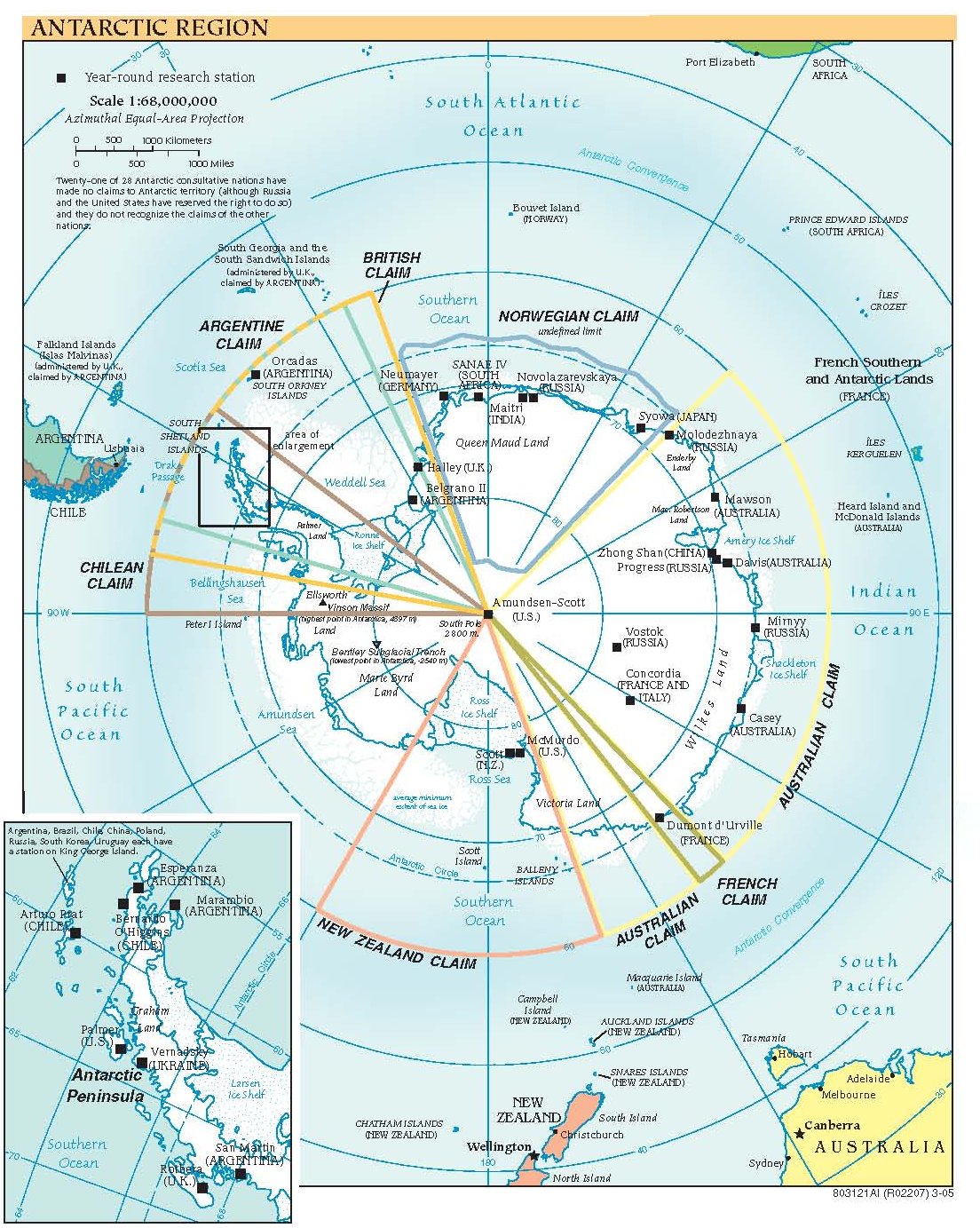

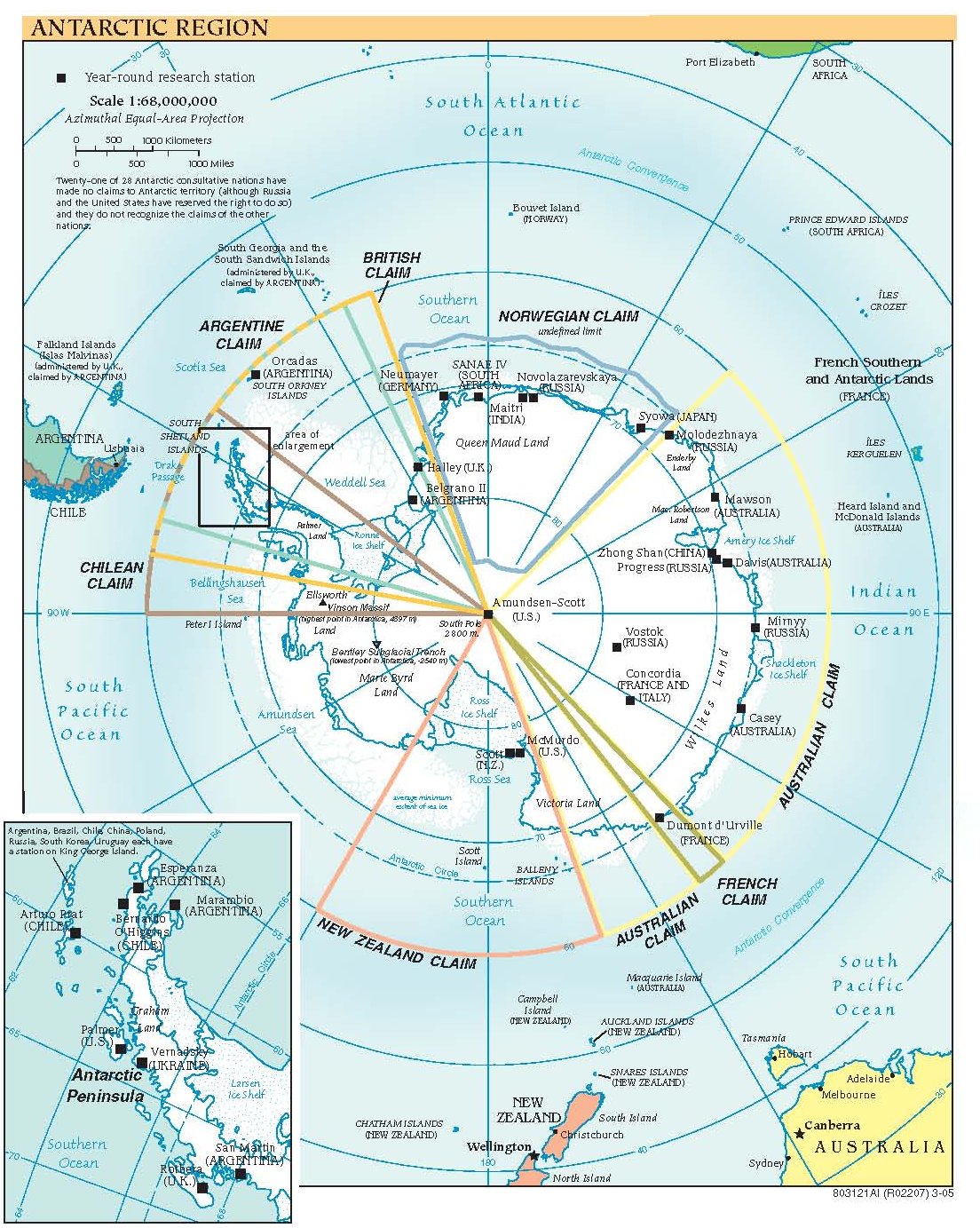

I am starting this new topic as the polar regions begin to gain more strategic importance, especially the Arctic. While there is a fairly robust system of treaties governing Antarctica (India joined the Treaty in c. 1983), the Arctic is largely governed by the eight-member Arctic Council. India joined the Arctic Council as an Observer in c. 2013. The Arctic is governed, apart from the eight members of the AC, by the UNCLOS and ISA (International Seabed Authority). China stakes a claim as a 'Near Arctic State'. The Arctic still remains very little understood even as it gets most affected by global weather changes.

Will fill up the above two place-holder posts with some information as I find more time.

Will fill up the above two place-holder posts with some information as I find more time.

Re: India's Polar Engagement: News & Discussion

India to have its first polar research vessel in five years: Union minister Kiren Rijiju - PTI

India aims to have its first Polar Research Vessel (PRV) in the next five years in order to sustain its bases in Antarctica, Union Earth Sciences Minister Kiren Rijiju said on Thursday. Replying to a query in the Rajya Sabha, he said a proposal regarding the ship is expected to go for Cabinet approval during the current financial year.

He noted that in 2014, the Cabinet had approved Rs 1,051 crore to acquire the vessel. A tender was also floated for the same.

The government later abandoned the project as the company which had got the order to build the ship raised certain conditions that were not part of the tender process.

"However another effort was initiated and now, we are ready with the proposal to be moved by the EFC (Expenditure Finance Committee)," Rijiju said.

The cost of the vessel is now estimated to be Rs 2,600 crore, he noted.

"I am hopeful that in this financial year, we should be ready to propose this estimate and move in the Cabinet. In the next five years, we should be ready with the ship," Rijiju stated.

He noted that the government is in talks with other countries which have expertise in making such ships.

Rijiju, however, noted that the government would like to manufacture the ship in the country itself.

"I am hopeful that in the next five years, we should be able to build the ship, hopefully in India," he said.

India currently has three research base stations in the polar region.

Rijiju said the country needs ice breaker ships to have continuous access to the research stations which are required for various reasons, especially to have a better understanding of climate change and other research matters.

A PRV not only performs research and logistics in the polar region but can also serve as a research platform for scientists to undertake research in the ocean realm, including the Southern Ocean.

Re: India's Polar Engagement: News & Discussion

Are we speaking of just Antarctic south polar region, or also north polar region? The north polar region seems to be a focus of increasing competition among the major powers. The heavy Russian investment in development of northern sea routes, including building of various large bases, and hydrocarbon resource exploitation in arctic polar region, has been a main driver. Even China has declared itself a "near arctic" state.

Re: India's Polar Engagement: News & Discussion

My post above answers.sanman wrote: ↑04 Aug 2023 16:14 Are we speaking of just Antarctic south polar region, or also north polar region? The north polar region seems to be a focus of increasing competition among the major powers. The heavy Russian investment in development of northern sea routes, including building of various large bases, and hydrocarbon resource exploitation in arctic polar region, has been a main driver. Even China has declared itself a "near arctic" state.

Re: India's Polar Engagement: News & Discussion

_You are cordially invited to_

Strategic Affairs Roundtable

*"The Geopolitics of the Arctic Circle"*

*Date*: Saturday, August 12th, 2023

*Time*: 10.00 AM EDT (Washington D.C.) | 7:30 PM IST (New Delhi)

*Distinguished Panelists*

Ambassador Anil Wadhwa

Dr. Sriparna Pathak

Kanagavalli Suryanarayanan

*Chair*

Dr. A. Adityanjee, President

Council for Strategic Affairs

*Registration*

Please register at https://bit.ly/csa12aug23 (redirect to Eventbrite)

(The meeting details will be sent with the registration confirmation email)

*About the Topic* (_Abstract_)

Geopolitical activity in the frozen Arctic has historically been fairly low. However, the onset of global warming is changing the region's geopolitical conditions. Over time, the Arctic melting is expected to reveal under-water resources and new shipping opportunities, which led to a fear of inter-state hostility in a scramble for new territories following the Russian flag planting on the North Pole sea bed in 2007. In reality, states bartered for unsettled territories in a peaceful manner after the Arctic states signed the 2008 Ilulissat Declaration committing themselves to peaceful cooperation, while events such as the Ukraine Crisis in 2014 had very marginal spill-over on the region. In 2019, most of the Arctic states are engaged in developing the governance of the region, such as bilateral agreements and Search and Rescue capabilities.

Having become a highly geopolitical area, the Arctic Council was formed in 1996 It was formed as a primary step towards a union of Arctic states in an attempt to coordinate a common strategy for states, communities and natural resources that were affected by changes in the Arctic circle. There were five member states in founding Arctic Five and understanding their role in Arctic geopolitics and international politics is important to comprehend the ongoing conflicts regarding the natural resources and developments in the Arctic area.

*About the Distinguished Panelists*

-- _Ambassador Anil Wadhwa_, Indian Foreign Service, Joined the Indian Foreign Service in 1979 and retired in 2017. Served as: Secretary (East) in the Ministry of External Affairs (2014-2016) with charge of Australasia and the Pacific, South East Asia, the Koreas, GCC, West Asia and North Africa. Ambassador of India to: Italy and San Marino (2016-2017) Thailand (2011-2014)· Sultanate of Oman (2007-2011) Poland and Lithuania (2004-2007), Other assignments abroad: Commission of India, Hongkong (1981-1983), Embassy of India, Beijing, PRC (1983-1987), Permanent Mission of India to the United Nations, Geneva (1989-1993), Organization for the prohibition of Chemical Weapons, The Hague (1993-2000). Was in the original group of 20 experts who designed, drafted, set up rules, and recruited for the international organization specializing in chemical industry and destruction of chemical weapons. In the course of a career of 38 years, in addition to political and strategic affairs, specialized in disarmament and economic relations. Represented India at international conferences, including as leader of senior officials level meetings of ASEAN, ASEM, BIMSTEC, East Asia Summit and Arab League; coordinated evacuation of Indian nationals from conflict zones of Iraq, Libya and Yemen; actively promoted Indian economic interests in areas of trade, investments into and out of India, and technology transfer. Served as Chairman of the Board of the World Food Programme (WFP), and Permanent Representative to the Food And Agriculture Organisation ( FAO) and International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), dealing with agricultural finance, development, planning and assistance.

-- _Dr. Sriparna Pathak_ is an Associate Professor and the founding Director of the Centre for Northeast Asian Studies in the Jindal, School of International Affairs (JSIA) of O.P. Jindal Global University, (JGU) Haryana, India. She is also the Associate Dean for Admissions at JSIA, JGU. She teaches courses on Foreign Policy of China as well as Theories of International Relations. She has recently published a book titled ‘Drifts and Dynamics.

-- _Kanagavalli Suryanarayanan_ is a law graduate and gold medallist from Pondicherry University and practices as an Advocate in India. She specialises in Intellectual Property Rights. She is the first Indian to pursue her Masters in Polar Law at the University of Akureyri. She has written on Arctic geopolitics and has been invited to several conferences on this topic.

*Further Information and Contact*

Ripudaman Pachauri | E-Mail: events@councilforstrategicaffairs.org

Strategic Affairs Distinguished Lecture is a presentation of

Council for Strategic Affairs councilforstrategicaffairs.org

Strategic Affairs Roundtable

*"The Geopolitics of the Arctic Circle"*

*Date*: Saturday, August 12th, 2023

*Time*: 10.00 AM EDT (Washington D.C.) | 7:30 PM IST (New Delhi)

*Distinguished Panelists*

Ambassador Anil Wadhwa

Dr. Sriparna Pathak

Kanagavalli Suryanarayanan

*Chair*

Dr. A. Adityanjee, President

Council for Strategic Affairs

*Registration*

Please register at https://bit.ly/csa12aug23 (redirect to Eventbrite)

(The meeting details will be sent with the registration confirmation email)

*About the Topic* (_Abstract_)

Geopolitical activity in the frozen Arctic has historically been fairly low. However, the onset of global warming is changing the region's geopolitical conditions. Over time, the Arctic melting is expected to reveal under-water resources and new shipping opportunities, which led to a fear of inter-state hostility in a scramble for new territories following the Russian flag planting on the North Pole sea bed in 2007. In reality, states bartered for unsettled territories in a peaceful manner after the Arctic states signed the 2008 Ilulissat Declaration committing themselves to peaceful cooperation, while events such as the Ukraine Crisis in 2014 had very marginal spill-over on the region. In 2019, most of the Arctic states are engaged in developing the governance of the region, such as bilateral agreements and Search and Rescue capabilities.

Having become a highly geopolitical area, the Arctic Council was formed in 1996 It was formed as a primary step towards a union of Arctic states in an attempt to coordinate a common strategy for states, communities and natural resources that were affected by changes in the Arctic circle. There were five member states in founding Arctic Five and understanding their role in Arctic geopolitics and international politics is important to comprehend the ongoing conflicts regarding the natural resources and developments in the Arctic area.

*About the Distinguished Panelists*

-- _Ambassador Anil Wadhwa_, Indian Foreign Service, Joined the Indian Foreign Service in 1979 and retired in 2017. Served as: Secretary (East) in the Ministry of External Affairs (2014-2016) with charge of Australasia and the Pacific, South East Asia, the Koreas, GCC, West Asia and North Africa. Ambassador of India to: Italy and San Marino (2016-2017) Thailand (2011-2014)· Sultanate of Oman (2007-2011) Poland and Lithuania (2004-2007), Other assignments abroad: Commission of India, Hongkong (1981-1983), Embassy of India, Beijing, PRC (1983-1987), Permanent Mission of India to the United Nations, Geneva (1989-1993), Organization for the prohibition of Chemical Weapons, The Hague (1993-2000). Was in the original group of 20 experts who designed, drafted, set up rules, and recruited for the international organization specializing in chemical industry and destruction of chemical weapons. In the course of a career of 38 years, in addition to political and strategic affairs, specialized in disarmament and economic relations. Represented India at international conferences, including as leader of senior officials level meetings of ASEAN, ASEM, BIMSTEC, East Asia Summit and Arab League; coordinated evacuation of Indian nationals from conflict zones of Iraq, Libya and Yemen; actively promoted Indian economic interests in areas of trade, investments into and out of India, and technology transfer. Served as Chairman of the Board of the World Food Programme (WFP), and Permanent Representative to the Food And Agriculture Organisation ( FAO) and International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), dealing with agricultural finance, development, planning and assistance.

-- _Dr. Sriparna Pathak_ is an Associate Professor and the founding Director of the Centre for Northeast Asian Studies in the Jindal, School of International Affairs (JSIA) of O.P. Jindal Global University, (JGU) Haryana, India. She is also the Associate Dean for Admissions at JSIA, JGU. She teaches courses on Foreign Policy of China as well as Theories of International Relations. She has recently published a book titled ‘Drifts and Dynamics.

-- _Kanagavalli Suryanarayanan_ is a law graduate and gold medallist from Pondicherry University and practices as an Advocate in India. She specialises in Intellectual Property Rights. She is the first Indian to pursue her Masters in Polar Law at the University of Akureyri. She has written on Arctic geopolitics and has been invited to several conferences on this topic.

*Further Information and Contact*

Ripudaman Pachauri | E-Mail: events@councilforstrategicaffairs.org

Strategic Affairs Distinguished Lecture is a presentation of

Council for Strategic Affairs councilforstrategicaffairs.org

Re: India's Polar Engagement: News & Discussion

The Arctic is the latest arena for NATO and Russia to flex their military muscle - Japan Times

A submarine snakes through a fjord in Norway alongside a British amphibious transport ship, as F-35 fighter jets roar overhead. NATO forces are gathered for a joint drill to repel a simulated invasion, albeit one where the enemy seems anything but theoretical.

President Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine may be raging thousands of kilometers to the south, but in the remote Arctic there is a close watch on his military activities. It’s an increasingly important region for energy, trade and security, and one where Russia, the U.S., China and others are vying for greater control.

The extent of Arctic seabed resources is not well mapped but estimates suggest the region holds around one-fourth of the globe’s oil and natural gas resources, while its sea routes could shave days if not weeks off traditional commercial shipping passages.

Moscow houses some of its most important strategic assets in the region including nuclear-capable attack submarines — and those could increase in importance as Putin seeks over time to reconstitute a military heavily depleted by the conflict in Ukraine.

Underpinning the drills is a sense that regardless of what happens in Ukraine (where Moscow’s troops are bogged down in a grinding war of attrition), NATO states are headed into a long-term climate of confrontation with Russia.

"We have to deal with a nation that has shown both the sort of willingness to, and also the ability to, use military power in an aggressive manner,” Rear Admiral Rune Andersen, Chief of the Royal Norwegian Navy, said on a recent sunny but frigid day on the bridge of the British Royal Navy warship HMS Albion. "That means that we need to be forward-looking and be prepared and also to deter any such action against any NATO country — that goes for this region as well as the Baltics and other parts of NATO territory.”

More than 20,000 troops from the U.K., the U.S., the Netherlands and six other nations are braving sub-20 degrees Celsius temperatures, ice and heavy snow to aid Norway, which in the fictitious war game faces a limited incursion from the north. The 11 day drills are training forces to survive and operate in remote Arctic areas.

With Finland and Sweden seeking to join the alliance, that will see seven out of eight Arctic nations in NATO. That means greater collective air, naval and artillery power as well as territory with railway networks to transport troops and equipment in the event of a conflict.

That united front may also serve to fan the narrative from the Kremlin that NATO is seeking to encircle it, and prompt Russia to bolster its own military presence there — if its war drain in Ukraine allows it, that is.

"If Russia wants to be a great power, if Russia wants to have a credible nuclear deterrent, if Russia wants to be in control of the immediate security environment in Northern Europe and also in the Arctic, it needs to have a very strong security and military position in the Arctic,” said Andreas Østhagen, a senior researcher at the Fridtjof Nansen Institute in Norway. "That’s not going to go away — it’s probably just going to increase once Sweden and Finland join NATO.”

An area of particular interest is the so-called Greenland-Iceland-U.K. gap, through which Russian vessels need to pass to access the Atlantic Ocean. Once there, Putin’s forces could potentially disrupt commercial shipping or cut off military supply lines for the U.S. to send reinforcements to Europe. Sabotaging underwater Transatlantic data cables could inflict widespread damage.

Putin appears to want to keep Russia visible in the Arctic even as his resources, particularly ground troops, are pulled into shoring up the campaign in Ukraine. Over the years he has reopened old Soviet-era military bases and built new ones. Around two-thirds of Russia’s nuclear-powered vessels, including ballistic missile submarines and nuclear attack submarines, are assigned to its Northern Fleet, based in the region’s Kola Peninsula.

The shortest route to North America from Russia is still over the top of the planet and Moscow’s new hypersonic missiles will require near-instantaneous reaction time from North American defenses, which are being modernized, military experts say.

Last year the Russian president unveiled a new maritime strategy, vowing to protect Arctic waters "by all means,” including with hypersonic Zircon missile systems. Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu announced plans to give Russia’s Arctic troops about 500 modern weapon systems and secure complete radar coverage of Arctic air space, although it is unclear if those goals were met in 2022. The Russian defense ministry reported regular drills in the Arctic last year, featuring one in September where troops trained on "defending Russian territories.”

In addition to safeguarding its strategic assets, Russia’s focus in the Arctic is — like other nations on preserving its economic interests, according to Rebecca Pincus, Director of the Polar Institute at the Wilson Center. Moscow wants to protect its northern trade routes and gain access to new fossil fuels and rare earth metal deposits as the ice melts due to climate change.

"Part of it was establishing the ability to protect, monitor, and control all this new traffic that they’re bringing in and all these resources that they want to develop,” Pincus said. "So the Russian impulse to build up military capabilities in the Russian Arctic makes sense.”

The Arctic is warming four times as fast as the rest of the world. Longer periods without ice mean increased marine traffic and potentially easier access to natural resources. About 90 billion barrels of undiscovered oil and 1,670 trillion cubic feet of undiscovered gas may lie inside the Arctic Circle, according to the United States Geological Survey, along with metals and minerals needed for electrification.

Last summer, both major shipping routes through the Arctic — Russia’s Northern Sea Route and Canada’s Northwest Passage — were essentially ice free all season. Climate scientists now predict the North Pole could be entirely ice-free by mid-century, opening a third Trans Arctic shipping route through international waters. This is seen as key to China’s Arctic strategy, which includes a Polar Silk Road connecting East Asia, Western Europe and North America.

China, which has touted its "no-limits” partnership with Russia, declared itself in 2018 a "near-Arctic state.” In addition to fishing, energy and transportation interests, China operates research stations in Norway and Iceland, and has pledged greater cooperation with Russia in the Arctic. The U.S. alleges a Chinese spy balloon recently entered its airspace over Alaska before eventually being shot down by American forces over South Carolina.

Economic imperatives may yet deter Russia from pursuing conflict in the Arctic, Pincus said.

Still, greater proximity of military forces is inherently dangerous. NATO has boosted its own presence in the region, including through military exercises and a command opened in Norfolk, Virginia, in 2021 that’s tasked with monitoring the Atlantic and High North, which includes areas both inside and outside of the Arctic circle.

In an op-ed in the Globe and Mail, which coincided with a visit to Canada last August, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg warned of China’s Arctic ambitions, and of Russia’s rising military activity in the region. "Russia’s ability to disrupt Allied reinforcements across the North Atlantic is a strategic challenge to the Alliance,” he said.

Russia’s highly advanced submarines pose one of the biggest challenges for the alliance in the Arctic, in particular because they are so hard to detect, maritime experts say. The Russian Navy commands an estimated 58 vessels, 11 of which are strategic nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines, according to the Nuclear Threat Initiative. That compares with the U.S.’s estimated 64 submarines, 14 of them ballistic missile submarines.

Underwater capability is an area where Russia can "present a sort of asymmetric threat against a more powerful Western alliance,” said the Norwegian Navy’s Andersen.

"The threat of an unlocated Russian submarine transiting from the North through the GIUK gap is a chief concern for NATO allies and something that warrants close coordination and cooperation across the alliance,” said Walter Berbrick, an associate professor at the U.S. Naval War College’s war gaming department and director of the Arctic Studies group.

NATO has responded by increasing underwater surveillance of the North Atlantic, with underwater sonar and maritime patrols by air. It’s an area where Finland and Sweden will be able to aid allies by monitoring and sharing intelligence — and providing vital air power.

Scandinavia will have about 250 fighter jets, including 150 F-35s, with Finland and Sweden in the NATO tent, said Norwegian Colonel Eirik Guldvog, Commanding Officer of the 133 Air Wing at Elvenes Military Airbase, north of the Arctic Circle in Norway. That compares with around 900 fighter jets for Russia’s air force, according to the World Directory of Modern Military Aircraft.

That’s on top of the P-8A Poseidon aircraft — including two from the U.S. — at the base that are used for maritime patrols, such as dropping sonar to look for submarines.

"This will be almost one air force, dealing with Scandinavia,” he said. "It will be quite a substantial air force.”

The importance of that was underscored last week. Even as the NATO drills went on, officials in Germany scrambled two F-35s at Elvenes after radar detected unidentified objects to the north. Within an hour, the jets were back, having got a close look at two Russian IL-38 jets traveling through international airspace.

It happens about once a week, Guldvog said, and the aircraft are invariably Russian as its air force looks to soak up information in the Arctic about other countries.

Guldvog's station has the most intercepts each year, "because Russia, to get to the Atlantic, they have to travel north of Norway and along our coast,” he said.

"We see a lot of flying, of course, northwards towards Canada and the U.S. over the North Pole.”

KEYWORDS

Re: India's Polar Engagement: News & Discussion

https://archive.is/ev2IJ

China, Iran, and others are pushing the boundaries of what types of activities are sanctioned on the continent and are contemplating future territorial claims. Last fall, Shahram Irani, the commander of the Iranian navy, announced that Tehran had plans to build a permanent base in Antarctica, even going so far as to claim that Iran somehow had “property rights” in the South Pole. Then, in November, China’s largest ever Antarctic fleet arrived with some 460 personnel to build the country’s fifth research station on the continent. They completed their work in three months, and the station opened in February. Under the Antarctic Treaty, which governs activities on the continent, China’s expansion is entirely permissible. That the new station is legal doesn’t stop suspicion from brewing that China’s research stations could house activities with military utility, including for surveillance purposes. Research satellites might track ice shelf shifts on Monday and on Tuesday pivot to mapping force movements in Australia.

Antarctica offers reach into the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans. On and offshore, it boasts vast deposits of precious minerals, oil, and natural gas, as well as large krill fisheries. The continent is also central to global communications because it holds the clearest shot to space, as moisture in the air freezes, making Antarctic ground stations crucial for operating satellites.

But crucially, the regions are administered differently: the Arctic does not have a treaty system, while the Antarctic does. Geographically, the Arctic is a maritime domain, whereas Antarctica is a continental landmass.

The Arctic is not part of the global commons; it is a region encircled by undisputed land territories of eight states. During both world wars and the Cold War, the Arctic was a key theater. Since 1996, Arctic governance has been facilitated by the Arctic Council, an intergovernmental forum that promotes communication and environmental partnerships. In the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Arctic Council members decided to pause their work with the council while Russia served as its chair. The result was the effective disengagement of Russia from Arctic affairs. With the chair rotating to Norway in 2023, activities restarted but without Russia’s participation. In February, it was announced that there would be a gradual resumption of virtual working-group meetings, after some researchers raised alarm over the global implications of the continued absence of Russian Arctic climate data.

Although the Antarctic Treaty System has kept the region stable for decades, the return of great-power competition is bringing new instability to the South Pole as some countries try to subvert the system. China, for example, built its new research station without submitting the necessary environmental evaluations to treaty members, as required. Russian fishing vessels have spoofed their location in the Southern Ocean in attempts to hide illegal fishing activities in protected waters. These examples of failing to follow various obligations illustrate how states are testing how much they can get away with.

For example, Russia is known to have made station runways inaccessible and to have switched off station radios to block parties landing to conduct internal inspections. The treaty allows for inspections to be undertaken aerially, as well, which means inspection teams can technically inspect Russian Antarctic stations without stepping inside them.

China’s ability to construct its own icebreakers—with a rumored nuclear-powered icebreaker set to debut in a few years—sets Beijing apart from the United States and Australia when it comes to Antarctic capability and therefore, power. The United States has two icebreakers—the Healy and the Polar Star—which take turns catching fire and are consistently pushed well beyond their expected operational life. Australia, holding the largest sovereign claim to Antarctica, has a single icebreaker, which, although brand new, is unable to currently refuel efficiently at its home port. Both the United States and Australia find themselves renting icebreakers to prop up their national Antarctic activities.

Consider krill fisheries. Some parts of Antarctica’s waters are protected by a convention within the Antarctic Treaty System that sets up protected marine zones. In recent years, China has deployed fleets of so-called super trawlers, large boats that stay at sea for several weeks, to enhance its fishing capacity, and it has used the treaty system to exploit krill fisheries in the name of science. China sees a strategic interest in cornering the global fisheries market, positioning itself to be able to control the flow of global food chains and secure such critical resources for its population. The resource-rich waters of the Southern Ocean that surround Antarctica are certainly ripe for exploitation—and Beijing has put its distant-water fisheries strategy on steroids, increasing its presence in the region.

At a 2021 meeting, China and Russia vetoed the establishment of new marine protected areas in the Southern Ocean, with Beijing calling for “further scientific research” to identify the need for such zones. China’s move could be viewed as an effort to frustrate progress in the marine protection sphere, but more likely it is strategic: Beijing would like to know exactly how bountiful in fish these zones are—and continue fishing for so-called research purposes.

The United States’ strategic science hub—Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station—straddles all seven frozen territorial claims to the continent. The base hosts up to 150 U.S. personnel to conduct and support scientific research. Farther south, in summer, as many as 1,500 U.S. personnel operate at McMurdo Station. A third American station, Palmer, accommodates about 40 U.S personnel. Together, these stations send a strong signal of the United States’ presence on the continent. China also has a history of blending scientific research work with military activity, an approach it has now enshrined in law. Dubbed by the Chinese government “civil-military fusion,” all civilian research activities are now required to have military application or utility for China. This extends to China’s Antarctic footprint.

China has sought to use Antarctic Treaty System rules to advance its own interests. Consider its approach to Dome Argus, the highest point on the Antarctic continent. The ice dome provides the clearest (and shortest) shot to space, making it the ideal place from which to receive satellite activity. China is free to conduct research on the dome as it does via a research station in the area, but in 2019 it went further, attempting to assert de facto control over the dome. It proposed establishing an Antarctic Specially Managed Area—a zone provided for by the treaty system where a country can restrict and dictate access to (or over) an area. A country is allowed to establish such a zone only if it can prove that subsequent research activities in the same area are undermining its scientific research agenda. China claimed that this was the case, but its request was rejected given that Beijing was the only country carrying out research activities at that time in the area.

Although China’s cunning plans for Dome Argus were blocked, the issue will likely come up again. Dome Argus falls in the territory claimed by Australia. Given the country’s vital interest in the area, Australia must invest in adequate inland capabilities to reach the isolated area—including by ski, tractor, and helicopter. Presence is power in the barren wasteland that is Antarctica.