Kurdistan - An Indian National Interest

Kurdistan - An Indian National Interest

I am creating this thread to focus on Kurdistan, its history, its economy, its politics and most importantly its current occupation by other nations - Turks, Iranians and Arabs.

I am of the view that Kurdistan should be the foundation of Indian power projection in West Asia. And we should do our utmost to see to it that Kurdistan becomes Independent and United.

Please contribute!

Thanks

I am of the view that Kurdistan should be the foundation of Indian power projection in West Asia. And we should do our utmost to see to it that Kurdistan becomes Independent and United.

Please contribute!

Thanks

Re: Kurdistan - An Indian National Interest

X-Posted from West Asia - News & Discussions Thread

Published on Aug 09, 2011

By M.K. Bhadrakumar

Syria lays bare India’s foreign policy: Rediff Blogs

Syria is up for grabs, and the decision is about retaining a Shi'ite Crescent or doing away with it. Either India would end up pissing off the Saudis, with whom our relations have improved, or pissing off the Iranians beyond the little irritation we gave them due to our vote against them in the IAEA. This pissing off would be long term!

Indians should however play our own Great Game in West Asia! And what would that Great Game in West Asia be for India?

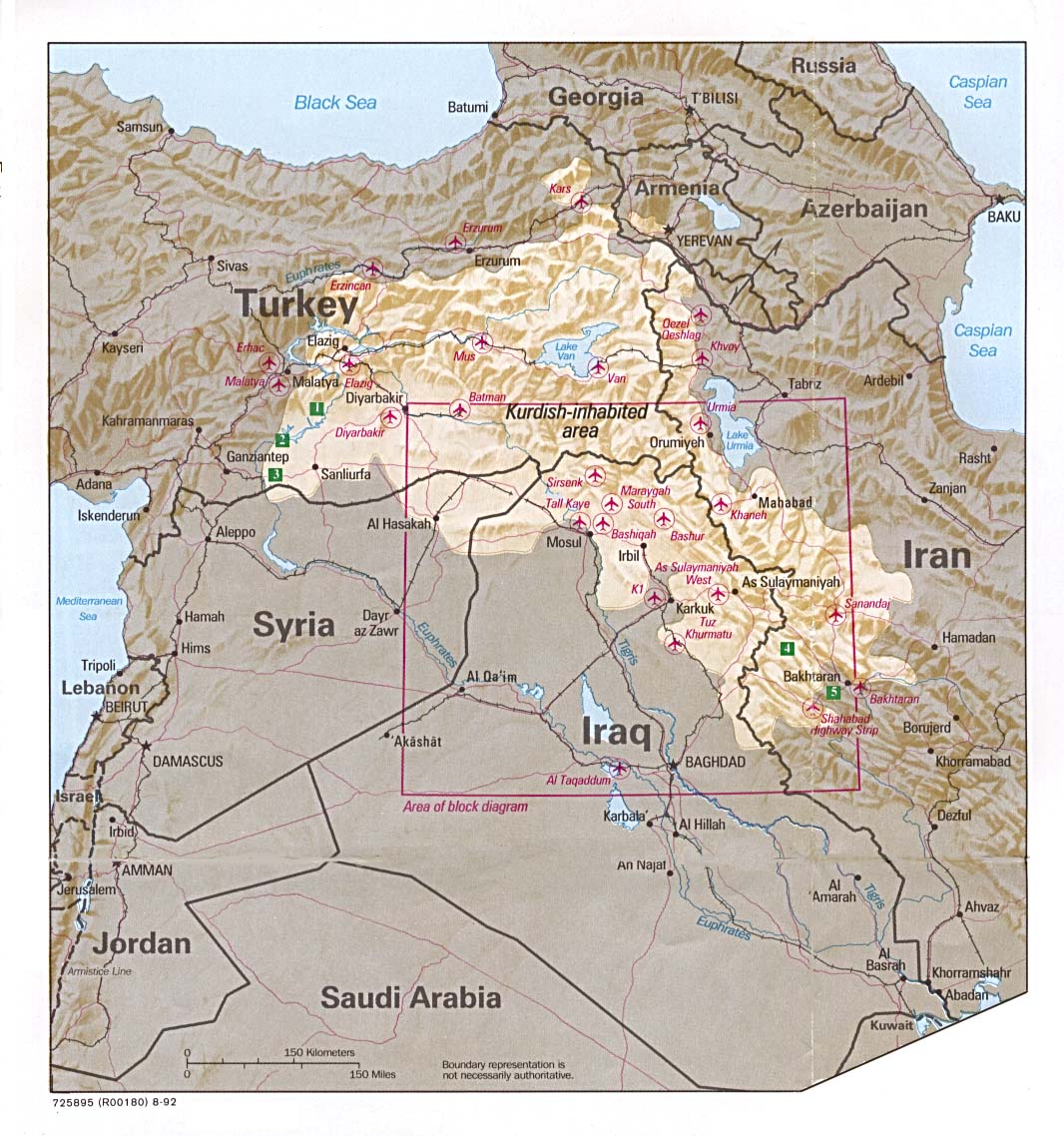

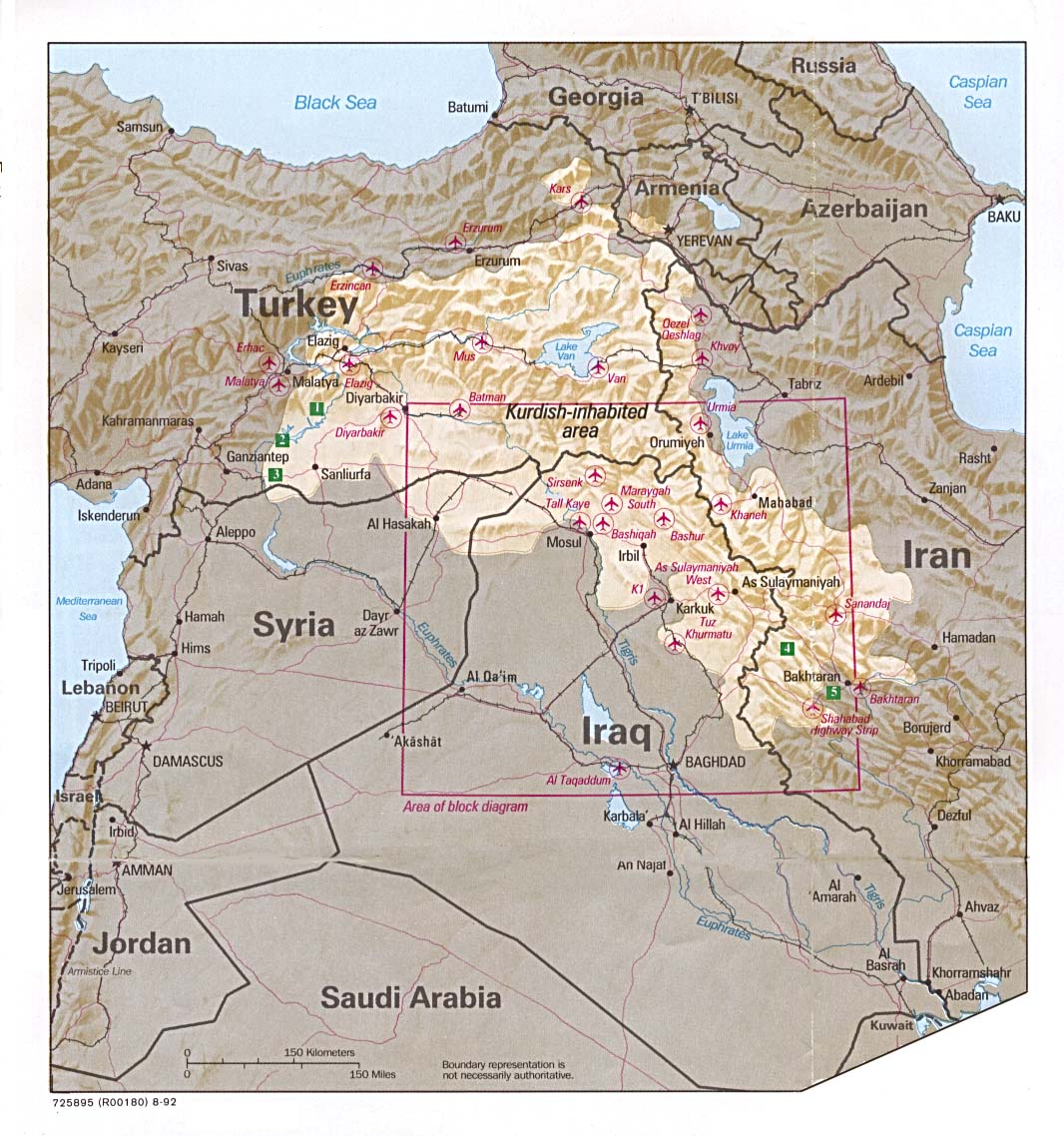

The foundation of our power in West Asia should be an Independent United Kurdistan consisting of parts of Kurdistan, today spread over four countries: Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Syria. Kurdistan should be today what once the Mittanis were in ancient times.

We should consider a break-up of Syria seriously, as it would help us create Syrian Kurdistan and join it up with Iraqi Kurdistan! That would be one more part of the puzzle solved, leaving us with the part in Iran and in Turkey.

Why Kurdistan?

Kurdish belongs to the Indo-European group of languages. It is closely linked with Baluchi language, and we propose to have Baluchistan as part of India someday. The Kurds are mostly a secular group, subjugated by other Muslim ethnicities - Turks, Persians, Arabs, etc. They will be very grateful for an Indian role in their liberation. So if USA has Israel in the Middle East as its power-base, we should develop Kurdistan as our power-base.

Some day, a much smaller Iran would build the geographical link between India (Baluchistan) and Kurdistan.

We should support the Alawites to create their own country in the North-West of Syria on the Mediterranean contiguous with Syrian Kurdistan. Also Syrian Christians can move to the North-West around Antioch and get some safe haven for themselves.

Thus the Shi'ite Crescent will be broken and the linkage would be through Kurdistan, a place where India would/could have a lot of influence. So we would control how much influence Iran can exert on the Mediterranean - in Lebanon, in North-West Syria. Of course, we would allow some, for North-West Syria would also give Kurdistan access to the sea.

Some day Iran too would throw away the yoke of Theocracy and even Islam itself and embrace its Aryan and Zoroastrian roots. Some day, Iran too may become a part of the Aryan Crescent stretching from India all the way to Mediterranean.

India too should develop long-term national interests in the region! As we grow into a power, we will need all the geostrategic space we can get!

However as many Indians like M.K. Bhadrakumar are still captive to Marxism, they are unable to see any Indian national interest anywhere, and presuppose that Indians will only be sucking up to one or the other power center in the world.

Published on Aug 09, 2011

By M.K. Bhadrakumar

Syria lays bare India’s foreign policy: Rediff Blogs

M.K. Bhadrakumar opines that India does not have any strategic interest in West Asia, only ideological reasons to vote one way or the other!India’s predicament is going to be acute. The plain truth is that geopolitics lie at the core of the Syrian crisis. Turkey has territorial ambitions over its former colony. It also has dreams of reclaiming the Ottoman legacy in the region. The NATO wants to arrive in the heart of the Muslim Middle East, which would be a huge leap out of Europe in its journey to become the premier global security organisation. For the US and Israel, the regime change in Damascus means the weakening of Hamas and it also opens the way to isolate Iran and Hezbollah, which in turn enables Israel to regain its regional dominance. The Sunni-Shi’ite schism provides the ideal backdrop for the US to retain its regional dominance over the strategically important Arab world — ‘divide-and-rule’. The Persian Gulf autocrats are hoping that Syria would divert attention away for a long while from their own rotting parishes.

All-in-all, the decision India takes at any UN Security Council process can only be viewed as ‘ideological’ insofar as it will be about: a) India’s strategic partnership with US and the need to harmonise with US regional policies; b) India’s dependence on the Jewish lobby in the US and the military ties with Israel; and, c) India’s time-tested friendship with the Syrian regime. If India votes with a US-Israeli-Saudi-Turkish move against the Syrian regime, will it bring India closer to UN Security Council membership? No way. Does India have stakes in the Sunni-Shi’ite schism that is going to tear apart the Muslim world? Certainly not. Does India have partisan interests in the Saudi-Iranian rivalry? Unlikely — even making allowance for the Saudi/Wahhabi/petrodollar clout over the ruling Congress Party in India’s domestic politics.

Finally, what happens if there is a regime change in Syria? Will it be any better than the chaos that unfolded in Iraq or Libya? Does India have any clear-cut vision to offer for a post-Assad Syria? Not even a brave heart in South Block will claim it has one. The strong likelihood is the emergence of the Islamist forces in yet another part of the Middle Eastern landscape. In sum, India’s stance on Syria in the UN is going to be something to write home about. It will lay bare the beating heart of India’s foreign policy establishment.

Syria is up for grabs, and the decision is about retaining a Shi'ite Crescent or doing away with it. Either India would end up pissing off the Saudis, with whom our relations have improved, or pissing off the Iranians beyond the little irritation we gave them due to our vote against them in the IAEA. This pissing off would be long term!

Indians should however play our own Great Game in West Asia! And what would that Great Game in West Asia be for India?

- India's Great Game should be to create a contiguous region of influence from India to the Mediterranean, and

- to break up every other power of consequence on the way, and

- to control the dynamics of the Sunni-Shia shism

- to control energy

The foundation of our power in West Asia should be an Independent United Kurdistan consisting of parts of Kurdistan, today spread over four countries: Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Syria. Kurdistan should be today what once the Mittanis were in ancient times.

We should consider a break-up of Syria seriously, as it would help us create Syrian Kurdistan and join it up with Iraqi Kurdistan! That would be one more part of the puzzle solved, leaving us with the part in Iran and in Turkey.

Why Kurdistan?

Kurdish belongs to the Indo-European group of languages. It is closely linked with Baluchi language, and we propose to have Baluchistan as part of India someday. The Kurds are mostly a secular group, subjugated by other Muslim ethnicities - Turks, Persians, Arabs, etc. They will be very grateful for an Indian role in their liberation. So if USA has Israel in the Middle East as its power-base, we should develop Kurdistan as our power-base.

Some day, a much smaller Iran would build the geographical link between India (Baluchistan) and Kurdistan.

We should support the Alawites to create their own country in the North-West of Syria on the Mediterranean contiguous with Syrian Kurdistan. Also Syrian Christians can move to the North-West around Antioch and get some safe haven for themselves.

Thus the Shi'ite Crescent will be broken and the linkage would be through Kurdistan, a place where India would/could have a lot of influence. So we would control how much influence Iran can exert on the Mediterranean - in Lebanon, in North-West Syria. Of course, we would allow some, for North-West Syria would also give Kurdistan access to the sea.

Some day Iran too would throw away the yoke of Theocracy and even Islam itself and embrace its Aryan and Zoroastrian roots. Some day, Iran too may become a part of the Aryan Crescent stretching from India all the way to Mediterranean.

India too should develop long-term national interests in the region! As we grow into a power, we will need all the geostrategic space we can get!

However as many Indians like M.K. Bhadrakumar are still captive to Marxism, they are unable to see any Indian national interest anywhere, and presuppose that Indians will only be sucking up to one or the other power center in the world.

Re: Kurdistan - An Indian National Interest

X-Posted from West Asia - News & Discussions Thread

ramana wrote:RajeshA, Might be OT but the extent of Indic thought and customs (Indic memes) in Asia is from East of Syria desert to Plain of Jars in Cambodia.

The West of the Syrian desert is out of area for Indic memes. All in between look to India for guidance for a large part of their history.

MKB has lost it long ago.

Re: Kurdistan - An Indian National Interest

X-Posted from West Asia - News & Discussions Thread

that (North-East) is about till where the Kurds are spread out, beyond that, that is why I am espousing an alliance with the Alawite-Syrian-Orthodox North-West Syrian country, separated from the Sunni Arab parts. That would bring Indian reach all the way to the Mediterranean, something I call the "Aryan Crescent".

ramana garu,ramana wrote:RajeshA, Might be OT but the extent of Indic thought and customs (Indic memes) in Asia is from East of Syria desert to Plain of Jars in Cambodia.

The West of the Syrian desert is out of area for Indic memes. All in between look to India for guidance for a large part of their history.

that (North-East) is about till where the Kurds are spread out, beyond that, that is why I am espousing an alliance with the Alawite-Syrian-Orthodox North-West Syrian country, separated from the Sunni Arab parts. That would bring Indian reach all the way to the Mediterranean, something I call the "Aryan Crescent".

Re: Kurdistan - An Indian National Interest

X-Posted from West Asia - News & Discussions Thread

Carl wrote:RajeshA ji, thanks for highlighting the importance of the stateless, brutalized, Kurdish nation.RajeshA wrote:The foundation of our power in West Asia should be an Independent United Kurdistan

Good point also about the Mittani-Indic connection to that part of the world. Apart from taking geostrategic positions on the evolving turmoil in the ME, there are many other things India can do to increase its own cultural and ideological footprint in that area (instead of the reverse as the idiot MKB suggests). For one, a lot of Kurdish cultural contributions have been subsumed under the "Iranian" rubric. These need to be distinguished. For example, most of the instruments used in Dastgahi classical music are of Kurdish, not Persian, origin. We need to invite their artists and help them raise their international profile. Secondly, Zoroastrianism also resonates deeply with them, while today's Iran defines itself primarily in pan-Islamist lines in order to project its power. If the external compulsion of that pan-Islamist logic were undermined, perhaps the Persians would come around to being comfortable in their true Indo-Aryan identity. Many other religious sects in Kurdistan, both explicitly non-Moslem as well as fringe Moslem, have echoes in India. Tremendous similarity between Sikhism and a couple of Kurdish sects, for example. All these need to be encouraged, via cultural, educational and tourism channels.

Re: Kurdistan - An Indian National Interest

Lecture given at Harvard University, 10 March 1993

By Dr. Mehrdad R. Izady

History of the Kurds: Lecture 1

Exploring Kurdish Origins

The question of Kurdish origins, i.e., who the Kurds are and where they come from, has for too long remained an enigma. Doubtless in a few words one can respond, for example, that Kurds are the end-product of numerous layers of cultural and genetic material superimposed over thousands of years of internal migrations, immigrations, cultural innovations and importations. But identifying the roots and the course of evolution of present Kurdish ethnic identity calls for a greater effort. It calls for the study of each of the many layers of these human movements and cultural influences, as many and as early in time as is currently possible. And to achieve this, one needs to delve deep into antiquity, and debate notions as diverse as anthropology, linguistics, genetics, theology, economics and demography, not to mention simple old narrative history.

Presently, at least 5 distinct layers can be identified with various degrees of certainty.

Halaf Cultural Period

The earliest evidence thus far of a unified and distinct culture shared by the people inhabiting the Kurdish mountains relates to the period of the ‘Halaf Culture’ that began around 8000 years ago. Named after the ancient mound of Tell Halaf west of the town of Qamishli in what is now the Syrian Kurdistan, this culture is best-known for its easily recognizable style of pottery which, fortunately, was produced in abundance. Exquisitely painted, delicately designed Halaf pottery are easily distinguishable from earlier and later productions. Judging from the pottery remains alone, Halaf culture appears to have been extant between 6000 to 5400 BC, a period of about 600 years.

In fact taking Halaf pottery as a prime example, many archaeologists now point out by that shared pottery style is a simple but crucial tool in helping to classify prehistoric cultures in the Middle East. Yet, while shared pottery can imply shared culture, it can no more imply shared ethnicity for the people who produced them than shared rug designs can now. Today, for example, the Turkic Qashqai, Luric Mamasani and the Arab Baseri peoples of southern Iran all share similar rug designs. Ethno-linguistically, however, these three peoples share virtually nothing else. This fact should serve as a clear warning to those who would use shared artistic styles and plastic arts as an indication of shared ethnicity. Pottery styles must be taken in tandem with other evidence in order to make a case for shared culture and ethnicity. But, wide-spread Halafian excavation sites have much more in common than styles of pottery.

Solid evidence has now emerged indicating striking similarities in food, technology, architecture, ritual practices and ornaments, all of which merge to suggest something more substantive. Archaeologist Julian Reade, now a curator at the British Museum’s Department of Western Asiatic Antiquities thus states: "While we really know little about how the inhabitants of a Halaf village thought, let alone what languages or languages they used for thinking, and what levels of abstraction could be expressed verbally, it seems likely they had comparable social structures, sharing many of the same implicit values, and that even those who did not travel regularly many have met from time to time in a religious or administrative centers." (footnote 1)

With the aid of these archaeological criteria, J. Reade as well as M. Roaf (archaeologist and former director of the British School of Archaeology in Iraq, now at the University of California, Berkeley) have determined the boundaries of the Halaf culture. They coincide almost exactly with the area the ethnic Kurds still call home: from Kirmanshah to Adyaman, and from Afrin near the Mediterranean Sea to northern areas of Lake Van. The distribution of the Halaf pottery and the distribution of ethnic Kurds today are a near-perfect match. The single exception is the Mosul-Tikrit region of the Mesopotamian lowlands. (footnote 2) James Mellaart, better known for his excavation at Catal Hüyük, meanwhile, has found many of the motifs and composite designs present on the Halaf pottery and figurines still extant in the textile and decorative designs of the modern Kurds who now inhabit the same excavated Halafian sites. (footnote 3)

It is highly unlikely that the Halaf people constituted an immigrant population. According to several demographic studies, the Zagros mountains were the site of perennial population surplus and pressure from 12000 to 5000 years ago, which must have resulted in many episodes of emigration. (footnote 4) This population pressure in the Zagros-Taurus folds was a consequence of successive technological advances in domestication of common crops and animals, and resulted in a prosperous agricultural economy and trade, ergo high population density. The Halafian phenomenon is likely the result of a massive internal migration which succeeded to culturally unify the population in Kurdistan.

The fact that the Halaf Culture spread so rapidly over such a considerable distance across the rugged Kurdish mountains is thought to have been the result of the development of a new life-style and economic activity necessitating mobility, namely nomadic herding. All the pre-requisite technologies had been developed and the necessary animals, particularly the dog, had now been domesticated by the settled agriculturists. The Halafian figurines of dogs (with jaunty upcurled tails uncharacteristic of any wolf), excavated from Jarmo in central Kurdistan is the earliest definitive evidence of the development of "man’s best friend" and the herder’s most prized protection. (footnote 5) Nomadic herding has since been a very mobile cornerstone of the Zagros-Taurus cultures and societies.

Ubaid Cultural Period

The Halaf Cultural period ends with the arrival, circa 5300 BC of a new culture and, quite likely a new people: the so-called Ubaidians.

Named after the archaeological mound of al-Ubaid in modern Iraq, where their remains first excavated, the people of Ubaid culture expanded in time from the plains of Mesopotamia into the mountains. The culture of the Ubaidians, or the proto-Euphratians, as they are sometimes called, caused a hybrid culture to emerge in the mountains. This new cultural phase in Kurdistan comprised of the earlier Halafian heritage, superimposed by this new, but foreign influence. The Ubaid cultural ascendance predominated in most of Kurdistan and Mesopotamia for the ensuing 1000 years.

Of the language and ethnic affiliation of the Ubaidians we know nothing beyond the barest conjecture. However, it is they who gave the names ‘Tigris’ and ‘Euphrates’ to the primary rivers of Kurdistan and Mesopotamia. (footnote 6)

Personally, I have come to suspect that the Ubaidian people may be identical or related to the enigmatic "Khaldi." The Khaldi are well represented in ancient Kurdistan, and were time Kurdicized to survive today as many Kurdish clans and tribes bearing variations of the old name, such as the modern Khallikan.(footnote 7) The modern survivors are found precisely were the classical Graeco-Roman sources recorded the Khaldi around 2000 years ago: mainly in northern and western Kurdistan. In support of this one may note the important fact that as the Ubaidians were found in lowland Mesopotamia as also in highland Kurdistan, the same is true of the Khaldi who were found in large numbers in both regions. Like their highland branch, the lowland Khaldi were also in time assimilated. In Mesopotamia, the Ubaidians were Semitized, becoming known as the celebrated Chaldeans.

The cultural impact of the Ubaidians on the mountain communities, nonetheless, was vast, although apparently it was not particularly deep.

Hurrian Cultural Period.

By approximately 4300 BC, a new culture, and possibly a new people, came to dominate the mountains: the Hurrians.

Of the Hurrians we know much more, and the volume of our knowledge becomes greater as the time becomes more recent. We know, for example, that the Hurrians spread far and wide into the Zagros-Taurus-Pontus mountain systems, and intruded for a time also on the neighboring plains of Mesopotamia and the Iranian Plateau. However, they never expanded too far from the mountains. Their economy was surprisingly integrated and focused, along with their political bonds, which runs largely parallel with the Zagros-Taurus-Pontus mountains, rather than radiating out to the lowlands, as was the case during the preceding Ubaid cultural period. Mountain-plain economic exchanges remained secondary in importance, judging by the archaeological remains of goods and their origin.

The Hurrians spoke a language, or properly, languages, of the north-eastern group of the Caucasic family of languages, distantly related to modern Chechen, Lezgian and Lakz. Their direction of Hurrian expansion is not yet understood, and by no means should be taken as having been north-south, i.e., an expansion out of the Caucasus, as often is presumed without any evidence. It may well be that it was the prolific Hurrians who introduced Northeast Caucasian languages into the Caucasus, instead of having originated from that tiny, sparsely-populated region.

For a long time the states founded by the Hurrians remained small, until around 2500 BC when larger political-military entities evolved out of the older, Hurrian city-states. Six polities are of special note: Urartu, Mushq/Mushku, Urkish, Subar/Saubar, Baini, Guti/Qutil and Manna. The kingdom of Mushku is now believed to have brought about the final downfall of the Hittites in Anatolia. Their name survives in the city of Mush/Mus in north-central Kurdistan of Turkey. The Subaru who operated from the areas north of modern Arbil in central Kurdistan have left their name in the populous and historic Kurdish tribal confederacy of Zubari, who still inhabit the areas north of Arbil.

The Guti/Qutils of central and southern Kurdistan, after gradually unifying the smaller mountain principalities, became strong enough in 2250 BC to actually annex Sumeria and the rest of lowland Mesopotamia. A Guti/Qutil dynasty ruled Sumeria for 130 years until 2120 BC.

Four legendary emporia, Arrap’ha, Melidi Washukani and Aratta served the Hurrians in their inter-regional trade with the economies outside the mountains. With certainty, Arrap’ha is to be identified with modern Kirkuk, Melidi with Malatya, while Washukani and Aratta are probably to be identified, respectively, with the rich archaeological sites of Godin Teppa (near Kangawar in southeastern Kurdistan, Iran) and Tell Fakhariya (west of Qamishli, in west-central Kurdistan, Syria). By the middle of the 2nd millennium BC, the culture and people of Kurdistan appear to have been unified under a Hurrian identity.

The legacy of the Hurrians to the present culture of the Kurds is fundamental. It is manifest in the realm of Kurdish religion, mythology, material and martial arts, and even the genetics. Nearly three-quarters of Kurdish clan names and roughly half of topographical and urban names are also of Hurrian origin, e.g., the names of the clans of Bukhti, Tirikan, Bazayni, Bakran, Mand; rivers Murad, Balik and Khabur, lake Van; the towns of Mardin, Ziwiya and Dinawar. Mythological and religious symbols present in the art of the later Hurrian dynasties, such as the Mannaeans and Kassites of eastern Kurdistan, and the Lullus of the southeast, present in part what can still be observed in the Kurdish ancient religion of Yazdanism, better-known today by its various denominations as Alevism, Yezidism, and Yarisanism (Ahl-i Haqq).

It is fascinating to recognize the origin of many tattooing motifs still used by the traditional Kurds on their bodies as replicas of those which appear on the Hurrian figurines. One such is the combination that incorporates serpent, sun disc, dog and comb/rain motifs. In fact some of these Hurrian tattoo motifs are also present in the religious decorative arts of the Yezidi Kurds, as found most prominently at the great shrine at Lalish.

By the end of the Hurrian period, Kurdistan seem to have been culturally and ethnically homogenized to form a single civilization which was identified as such by the neighboring cultures and peoples. Sumerians, for example, called everybody in the Kurdish mountains as "Subaru," while the Akkadians, Assyrians and Babylonians used the term "Guti/Qutil." To the ancient Jews, they were are all the "Qarduim." All these ancient appellations have modern representatives in the names of major Kurdish clans, and were by no means the artifacts of the imagination of those early Mesopotamians. The lowlanders of Mesopotamia must have seen the uniformity of the culture (and presumably the ethnicity) of the peoples of the Kurdish mountains, prompting them to call these mountaineers by a single native ethnic/tribal name that was most familiar to them at any given time. Likewise, today we know all of these same mountain people as Kurds. This portrait of a culturally homogenized Kurdistan was not to last.

By Dr. Mehrdad R. Izady

History of the Kurds: Lecture 1

Exploring Kurdish Origins

The question of Kurdish origins, i.e., who the Kurds are and where they come from, has for too long remained an enigma. Doubtless in a few words one can respond, for example, that Kurds are the end-product of numerous layers of cultural and genetic material superimposed over thousands of years of internal migrations, immigrations, cultural innovations and importations. But identifying the roots and the course of evolution of present Kurdish ethnic identity calls for a greater effort. It calls for the study of each of the many layers of these human movements and cultural influences, as many and as early in time as is currently possible. And to achieve this, one needs to delve deep into antiquity, and debate notions as diverse as anthropology, linguistics, genetics, theology, economics and demography, not to mention simple old narrative history.

Presently, at least 5 distinct layers can be identified with various degrees of certainty.

Halaf Cultural Period

The earliest evidence thus far of a unified and distinct culture shared by the people inhabiting the Kurdish mountains relates to the period of the ‘Halaf Culture’ that began around 8000 years ago. Named after the ancient mound of Tell Halaf west of the town of Qamishli in what is now the Syrian Kurdistan, this culture is best-known for its easily recognizable style of pottery which, fortunately, was produced in abundance. Exquisitely painted, delicately designed Halaf pottery are easily distinguishable from earlier and later productions. Judging from the pottery remains alone, Halaf culture appears to have been extant between 6000 to 5400 BC, a period of about 600 years.

In fact taking Halaf pottery as a prime example, many archaeologists now point out by that shared pottery style is a simple but crucial tool in helping to classify prehistoric cultures in the Middle East. Yet, while shared pottery can imply shared culture, it can no more imply shared ethnicity for the people who produced them than shared rug designs can now. Today, for example, the Turkic Qashqai, Luric Mamasani and the Arab Baseri peoples of southern Iran all share similar rug designs. Ethno-linguistically, however, these three peoples share virtually nothing else. This fact should serve as a clear warning to those who would use shared artistic styles and plastic arts as an indication of shared ethnicity. Pottery styles must be taken in tandem with other evidence in order to make a case for shared culture and ethnicity. But, wide-spread Halafian excavation sites have much more in common than styles of pottery.

Solid evidence has now emerged indicating striking similarities in food, technology, architecture, ritual practices and ornaments, all of which merge to suggest something more substantive. Archaeologist Julian Reade, now a curator at the British Museum’s Department of Western Asiatic Antiquities thus states: "While we really know little about how the inhabitants of a Halaf village thought, let alone what languages or languages they used for thinking, and what levels of abstraction could be expressed verbally, it seems likely they had comparable social structures, sharing many of the same implicit values, and that even those who did not travel regularly many have met from time to time in a religious or administrative centers." (footnote 1)

With the aid of these archaeological criteria, J. Reade as well as M. Roaf (archaeologist and former director of the British School of Archaeology in Iraq, now at the University of California, Berkeley) have determined the boundaries of the Halaf culture. They coincide almost exactly with the area the ethnic Kurds still call home: from Kirmanshah to Adyaman, and from Afrin near the Mediterranean Sea to northern areas of Lake Van. The distribution of the Halaf pottery and the distribution of ethnic Kurds today are a near-perfect match. The single exception is the Mosul-Tikrit region of the Mesopotamian lowlands. (footnote 2) James Mellaart, better known for his excavation at Catal Hüyük, meanwhile, has found many of the motifs and composite designs present on the Halaf pottery and figurines still extant in the textile and decorative designs of the modern Kurds who now inhabit the same excavated Halafian sites. (footnote 3)

It is highly unlikely that the Halaf people constituted an immigrant population. According to several demographic studies, the Zagros mountains were the site of perennial population surplus and pressure from 12000 to 5000 years ago, which must have resulted in many episodes of emigration. (footnote 4) This population pressure in the Zagros-Taurus folds was a consequence of successive technological advances in domestication of common crops and animals, and resulted in a prosperous agricultural economy and trade, ergo high population density. The Halafian phenomenon is likely the result of a massive internal migration which succeeded to culturally unify the population in Kurdistan.

The fact that the Halaf Culture spread so rapidly over such a considerable distance across the rugged Kurdish mountains is thought to have been the result of the development of a new life-style and economic activity necessitating mobility, namely nomadic herding. All the pre-requisite technologies had been developed and the necessary animals, particularly the dog, had now been domesticated by the settled agriculturists. The Halafian figurines of dogs (with jaunty upcurled tails uncharacteristic of any wolf), excavated from Jarmo in central Kurdistan is the earliest definitive evidence of the development of "man’s best friend" and the herder’s most prized protection. (footnote 5) Nomadic herding has since been a very mobile cornerstone of the Zagros-Taurus cultures and societies.

Ubaid Cultural Period

The Halaf Cultural period ends with the arrival, circa 5300 BC of a new culture and, quite likely a new people: the so-called Ubaidians.

Named after the archaeological mound of al-Ubaid in modern Iraq, where their remains first excavated, the people of Ubaid culture expanded in time from the plains of Mesopotamia into the mountains. The culture of the Ubaidians, or the proto-Euphratians, as they are sometimes called, caused a hybrid culture to emerge in the mountains. This new cultural phase in Kurdistan comprised of the earlier Halafian heritage, superimposed by this new, but foreign influence. The Ubaid cultural ascendance predominated in most of Kurdistan and Mesopotamia for the ensuing 1000 years.

Of the language and ethnic affiliation of the Ubaidians we know nothing beyond the barest conjecture. However, it is they who gave the names ‘Tigris’ and ‘Euphrates’ to the primary rivers of Kurdistan and Mesopotamia. (footnote 6)

Personally, I have come to suspect that the Ubaidian people may be identical or related to the enigmatic "Khaldi." The Khaldi are well represented in ancient Kurdistan, and were time Kurdicized to survive today as many Kurdish clans and tribes bearing variations of the old name, such as the modern Khallikan.(footnote 7) The modern survivors are found precisely were the classical Graeco-Roman sources recorded the Khaldi around 2000 years ago: mainly in northern and western Kurdistan. In support of this one may note the important fact that as the Ubaidians were found in lowland Mesopotamia as also in highland Kurdistan, the same is true of the Khaldi who were found in large numbers in both regions. Like their highland branch, the lowland Khaldi were also in time assimilated. In Mesopotamia, the Ubaidians were Semitized, becoming known as the celebrated Chaldeans.

The cultural impact of the Ubaidians on the mountain communities, nonetheless, was vast, although apparently it was not particularly deep.

Hurrian Cultural Period.

By approximately 4300 BC, a new culture, and possibly a new people, came to dominate the mountains: the Hurrians.

Of the Hurrians we know much more, and the volume of our knowledge becomes greater as the time becomes more recent. We know, for example, that the Hurrians spread far and wide into the Zagros-Taurus-Pontus mountain systems, and intruded for a time also on the neighboring plains of Mesopotamia and the Iranian Plateau. However, they never expanded too far from the mountains. Their economy was surprisingly integrated and focused, along with their political bonds, which runs largely parallel with the Zagros-Taurus-Pontus mountains, rather than radiating out to the lowlands, as was the case during the preceding Ubaid cultural period. Mountain-plain economic exchanges remained secondary in importance, judging by the archaeological remains of goods and their origin.

The Hurrians spoke a language, or properly, languages, of the north-eastern group of the Caucasic family of languages, distantly related to modern Chechen, Lezgian and Lakz. Their direction of Hurrian expansion is not yet understood, and by no means should be taken as having been north-south, i.e., an expansion out of the Caucasus, as often is presumed without any evidence. It may well be that it was the prolific Hurrians who introduced Northeast Caucasian languages into the Caucasus, instead of having originated from that tiny, sparsely-populated region.

For a long time the states founded by the Hurrians remained small, until around 2500 BC when larger political-military entities evolved out of the older, Hurrian city-states. Six polities are of special note: Urartu, Mushq/Mushku, Urkish, Subar/Saubar, Baini, Guti/Qutil and Manna. The kingdom of Mushku is now believed to have brought about the final downfall of the Hittites in Anatolia. Their name survives in the city of Mush/Mus in north-central Kurdistan of Turkey. The Subaru who operated from the areas north of modern Arbil in central Kurdistan have left their name in the populous and historic Kurdish tribal confederacy of Zubari, who still inhabit the areas north of Arbil.

The Guti/Qutils of central and southern Kurdistan, after gradually unifying the smaller mountain principalities, became strong enough in 2250 BC to actually annex Sumeria and the rest of lowland Mesopotamia. A Guti/Qutil dynasty ruled Sumeria for 130 years until 2120 BC.

Four legendary emporia, Arrap’ha, Melidi Washukani and Aratta served the Hurrians in their inter-regional trade with the economies outside the mountains. With certainty, Arrap’ha is to be identified with modern Kirkuk, Melidi with Malatya, while Washukani and Aratta are probably to be identified, respectively, with the rich archaeological sites of Godin Teppa (near Kangawar in southeastern Kurdistan, Iran) and Tell Fakhariya (west of Qamishli, in west-central Kurdistan, Syria). By the middle of the 2nd millennium BC, the culture and people of Kurdistan appear to have been unified under a Hurrian identity.

The legacy of the Hurrians to the present culture of the Kurds is fundamental. It is manifest in the realm of Kurdish religion, mythology, material and martial arts, and even the genetics. Nearly three-quarters of Kurdish clan names and roughly half of topographical and urban names are also of Hurrian origin, e.g., the names of the clans of Bukhti, Tirikan, Bazayni, Bakran, Mand; rivers Murad, Balik and Khabur, lake Van; the towns of Mardin, Ziwiya and Dinawar. Mythological and religious symbols present in the art of the later Hurrian dynasties, such as the Mannaeans and Kassites of eastern Kurdistan, and the Lullus of the southeast, present in part what can still be observed in the Kurdish ancient religion of Yazdanism, better-known today by its various denominations as Alevism, Yezidism, and Yarisanism (Ahl-i Haqq).

It is fascinating to recognize the origin of many tattooing motifs still used by the traditional Kurds on their bodies as replicas of those which appear on the Hurrian figurines. One such is the combination that incorporates serpent, sun disc, dog and comb/rain motifs. In fact some of these Hurrian tattoo motifs are also present in the religious decorative arts of the Yezidi Kurds, as found most prominently at the great shrine at Lalish.

By the end of the Hurrian period, Kurdistan seem to have been culturally and ethnically homogenized to form a single civilization which was identified as such by the neighboring cultures and peoples. Sumerians, for example, called everybody in the Kurdish mountains as "Subaru," while the Akkadians, Assyrians and Babylonians used the term "Guti/Qutil." To the ancient Jews, they were are all the "Qarduim." All these ancient appellations have modern representatives in the names of major Kurdish clans, and were by no means the artifacts of the imagination of those early Mesopotamians. The lowlanders of Mesopotamia must have seen the uniformity of the culture (and presumably the ethnicity) of the peoples of the Kurdish mountains, prompting them to call these mountaineers by a single native ethnic/tribal name that was most familiar to them at any given time. Likewise, today we know all of these same mountain people as Kurds. This portrait of a culturally homogenized Kurdistan was not to last.

Re: Kurdistan - An Indian National Interest

Lecture given at Harvard University, 10 March 1993

By Dr. Mehrdad R. Izady

History of the Kurds: Lecture 2

The Aryan Period

As early as 2000 BC, the vanguards of the Indo-European speaking tribal immigrants, such as the Hittites and the Mittanis (Sindis), had arrived in southwestern Asia. While the Hittites only marginally affected the mountain communities in Kurdistan, the Mittanis settled inside Kurdistan around modern Diyarbakir, and influenced the natives in several fields worthy of note, in particular the introduction of knotted rug weaving. Even rug designs introduced by the Mittanis and recognized by the replication in the Assyrian floor carvings, remain the hallmark of the Kurdish rugs and kelims. The modern mina khâni and chwar such styles are basically the same today as those the Assyrians copied and depicted nearly 3000 years ago.

The name ‘Mittani’ survives today in the Kurdish clans of Mattini and Motikan/Moti who inhabit the exact same geographical areas of Kurdistan as the ancient Mittani. The name "Mittan," however, is a Hurrian name rather than Aryan. At the onset of Aryan immigration into Kurdistan, only the aristocracy of the high-ranking warrior groups were Aryans, while the bulk of the people were still Hurrian in all manners. The Mittani aristocratic house almost certainly was from the immigrant Sindis, who survive today in the populous Kurdish clan of Sindi—again—in the same area where the Mittani kingdom once existed. These ancient Sindi seem to have been an Indic, and not Iranic group of people, and in fact a branch of the better known Sindis of India-Pakistan, that has imparted its name to the River Indus and in fact, India itself. (footnote 8 ) While the bulk of the Sindis moved on to India, some wondered into Kurdistan to give rise to the Mittani royal house and the modern Sindi Kurds. Others, still, remained in Europe, and are recorded in the 1st century AD inhabiting the Taiman Peninsula on the Sea of Azov between Russia and Ukraine.

Expectedly, the Mittani pantheon includes names like Indra, Varuna, Suriya and Nasatya is typically Indic. The Mittanis could have introduced during this early period some of the Indic/Vedic tradition that appears to be manifest in the Kurdish religion of Yazdanism.

The avalanche of the Indo-European tribes, however, was to come about 1200 BC, raining havoc on the economy and settled culture in the mountains and lowlands alike. The north was settled by the Haigs who are known to us now as the Armenians, while the rest of the mountains became targets of settlement of various Iranic peoples, such as the Medes, Persian, Scythians, Sarmatians, and Sagarthians (whose name survives in the name of the Zagros mountains).

By 850 BC, the last Hurrian states had been extinguished by the invading Aryans, whose sheer number of immigrants must have been considerable. These succeeded over time to change the Hurrian language(s) of the people in Kurdistan, as well as their genetic make-up. By about the 3rd century BC, the Aryanization of the mountain communities was virtually complete.

Since the star of the Mittani shown brightest in 1500 BC, Aryan dynasties of various size and influence continued their appearance in various corners of Kurdistan. None, however, was to match, and in fact surpass the Mittanis as the Medians. The rise of the Medes from their capital at Ecbatana (modern Hamadan) in 727 coincided with the fall of the last major Hurrian kingdom: the Mannaeans. Ignoring the proud legacy of the Hurrian states and even the Aryan empire of the Mittanis which can squarely be claimed by on every ground by modern Kurds, it is the Medes that the Kurds have grown most fund of. Medes are claimed regularly by the Kurds and pronounced by others to be the ancestors of them. This is strange, when realizing how many millennia of cultural and ethnic evolution preceded the rise of Medes into Kurdistan. In reality, Medes are no more the ancestors of the modern Kurds as all other Halafian, Hurrian and Mittani who came before them or the legion of other peoples and states that came after them. Nonetheless, today, even the first Kurdish satellite television transmitter is given the name "Med TV" (Kurdish for "Median TV"). Fascination of the Kurds with the Median Federation (a.k.a., Empire) that ended in 549 BC remains supreme, indeed.

It is surprising to most that among the Kurds the Aryan cultural was and still remains secondary to that of the Hurrians. Culturally, Aryan nomads brought very little with to add to what they found already present in the Zagros-Taurus region. As has been the case, cultural sophistication and civilization are not what nomads are known for. On the contrary, nomads are inclined to annihilate what settled life and culture they find in their path as adversaries for possession of land and political dominance. We have no ample evidence, including a bona fide economic dark age lasting for roughly 500 years in the areas touched by the Aryans, that they behaved much the same barbarian way.

The Aryan influence on the local Hurrian Kurdish people must have been very similar to what transpired in Anatolia 2,500 years later when the Turkic nomads broke in after the battle of Manzikert in AD 1071. Much insight can be learned from this more recent nomadic dislocation for the older, murkier Aryan episode. Following the Manzikert, the Turkic nomads gradually imparted their language to all the millions of civilized, sophisticated Anatolians whom they converted from Christianity to their own religion of Hanafi Sunni Islam. Almost everyone in Anatolia gradually assumed a new Turkish identity when converted to Islam. But, this did not mean that the old cultural, human and genetic legacy ceased to exist. On the contrary, the rich and ancient Anatolian cultures and peoples continued their existence under the new Turkish identity, albeit, with the addition of some genetic and cultural material brought over by the nomads.

Architecture, domestic and monumental, decorative arts, farming techniques, herding practices, and religion remained much the same in Kurdistan following Aryan settlement, while the people progressively came to speak the Indo-European, Iranic language of these Aryan immigrants, admit new deities into their earlier Hurrian pantheon, and become lighter in their complexion. No abrupt change is encountered in the culture of Kurdistan while this linguistic and genetic shift was taking place under the Aryan pressure, barring the appearance of the so-call, "gray ware" pottery.

Near every thing in the contemporary culture of the Kurds can be traced to this massive Hurrian substructure, with the Aryan superstructure generally quite superficial and "skin deep"—to use a pun, in many fundamental ways. Even the time-honored Kurdish tactic of guerrilla warfare finds its roots among the Hurrian Gutis long before its was put into good use as a well-tested and developed tactic by the Median Cyaxares in this Assyrian campaigns in 612 BC. In the Bisitun inscription, the Persian king Darius I also makes note of this battle tactic used by the mountaineers against his forces, calling the guerrillas the kara (a lexical cognate of the term, "guerrilla"). Eight hundred years later, King Ardasher, founder of the Persian Sasanian dynasty, faces the same defensive tactics by the Kurds. The term he uses for them is jan-spâr, which means almost identical with the modern term Kurds give their guerrilla warriors: the peshmerga.

So far the victory cylinder of the Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser I (r. 1114-1076 BC) is the oldest record of the incidence of the ethnic name of the Kurds. It records the "Kurti" or "Qurtie" among the peoples whom the king conquered in his mountain campaigns south of the Lake Van region. The more exact location of these "Kurti" is given by the same document as Mt. Azu/Hazu. We are extraordinarily lucky that this "address" was still current until about sixty years ago—over 3100 years after Tiglath-pileser I. The town of Kurti in the Mt. Hizan region south of Lake Van is the same as the "Kurti in the Mt. Azu" of the Assyrians. The town of Kurti was still serving as a seat of a Kurdish princely house when the Kurdish historian Sharaf al-Din Bitlisi added the dynasty’s history into his celebrated history, the Sharafnâma, in 1597. This "birthplace" of the Kurds continued to be known with the archaic name until the Turkish government changed its name and that of its eponymous river, respectively, to Aksar (at 38.30 N, 42.49 E) and Büyük river in the 1930s. The oldest Kurdish place name—its "birth place" thus joined history so recent in history.

The Akkadian term "Kurti" denoted vaguely and indeterminate portion or groups of inhabitants of the Zagros (and eastern Taurus) mountains. To their very end in the 6th century BC, on the other hand, the Babylonians loosely (and apparently pejoratively) called most every body who lived in the Zagros-Taurus system a "Guti", including the Medes! But Babylonian records also attest to many more specific subdivisional names such as the Mardi, Kardaka, Lullubi and Qardu, the last three of which have all been used frequently in the needless controversy over the roots and antiquity of the ethnic term ‘Kurd,’ and the question of the presence of a general ethnic designator.

By the 3rd century BC, at any rate, the very term Kurd (or rather "Kurti") had been conclusively established. Polybius (d. ca. 133 BC) in his history when reporting on the events of 221-220 BC, (footnote 9) and Strabo (d. ca. AD 48) in his geography (footnote 10) are the earliest Western sources I am aware of to have made mention of the Kurds with their present ethnic name, albeit, in latinized form Cyrtii, "the Kurti." Historians Livy, Pliny, Plutarch, and much later, Procopius also mention this ethnic name for the native population of Media and parts of Anatolia for the classical times. Ptolemy inadvertently provides us with an array of Kurdish tribal names, when he records them as they appear as toponyms for where the tribe resided. Bagraoandene for the Bagrawands or Bakrans of Diyarbakir, Belcanea for the Belikans of Antep, Tigranoandene for the Tirigans of Hakkari, Sophene for the Subhans of Elazig, Derzene for the Dersimis and Bokhtanoi for the Bokhti (Bohtans) etc. These tribes are still with us today.

When the Aryan Medes and Persians arrived on the eastern flanks of the Zagros around 1000 BC, a massive internal migration from the eastern Taurus and northern and central Zagros toward the southern Zagros was in progress. By the 6th century BC, many large tribes which we now find among the Kurds were also present in southern Zagros, in Fars and even Kirman. As early as the 3rd century BC, the "Kurtioi" are reported by the Greek, and later Roman authors (in the Latin form of "Cyrtii") to inhabit as much the southern Zagros (Persis or Pars/Fars) as the central and northern Zagros (Kurdistan proper). This was to continue for another millennium, by which time, the ethnic name of "Kurd" had become established for nearly all if not all inhabitants of the mountains, from the Straits of Hormuz to the heart of Anatolia. Northern Zagros and Anatolia once teamed with various and related groups of people speaking Iranic tongue(s). By about 2000 years ago, many of these, such as the Iranic Pontians, Commagenes, Cappadocians, the western Medes and the Indic Mitannis, like the earlier Hurrian Mannas, Lullus, Saubarus, Kardakas, and Qutils, had been totally absorbed into a new Kurdish ethnic pool. These are among many mountain-inhabiting peoples whose assimilation has formed genetically, culturally, socially and linguistically the contemporary Kurds. The Kurdish diversity of race, tradition and spoken dialects encountered today point to the direction of this compound identity.

Reflecting on the gradual and organic assimilation of one of these groups into the larger Kurdish ethnic pool, Pliny the Elder (d. AD 79) tries to reconcile what appeared to him to be rather a name-change for a familiar people. Enumerating the nations of the known world, he states, "Joining on to Adiabene [central Kurdistan centered on Arbil] are the people formerly called the Carduchi [the Kardukh] and now the Cordueni past whom flows the river Tigris…" (footnote 11)

These Carduchi mentioned by Pliny are the same people whom Xenophon and his fellow ten thousand Greek troops had encountered nearly three centuries earlier when retreating through Kurdistan in 401 BC. Xenophon called them the “Kardukhoi” The name is likely the same as that of ‘Kardaka,’ (the people who provided a part of the Babylonian royal guards before 530 bc), and the ‘Qarduim’ (mentioned frequently in the Talmud). (footnote 12)

The early Islamic sources enumerate tens of Kurdish tribes and family clans outside Kurdistan proper in the southern Zagros, the Caucasus, Elburz, Taurus and Amanus mountains. In time, however, all of these assimilated into the local. This fact has been an unwarranted source of puzzlement for many modern writers on Kurdish history. Unaware of the history and extent of early Kurdish migrations and finding, at present, very few Kurds in these other mountain areas, they have often drawn the wrong conclusion that the term "Kurd" could not have been an ethnic name but rather a designator for all mountain nomads in general. This facile hypothesis is hardly worthy of refutation, realizing that no such doubt is cast on any other mobile nations such as the Turks and that Arabs who have spread and contracted periodically over thousands of miles of territory. (footnote 13)

From the time the Kurds are Aryanized until the 16th century of our era, the Kurdish culture remained basically unchanged, despite introduction of new empires, religions, and immigrants. The Kurds remained primarily followers of the ancient, Hurrian religion of Yazdanism, spoke an Iranic language that the medieval Islamic sources termed Pahlawani. Pahlawani survives today in the dialects of Gurani and Dimili (Zaza) on the peripheries of Kurdistan. Only the loss of Kurds of the southern Zagros through their metamorphosis into Lurs and a fresh expansion of Kurds into Elbruz and Pontus mountains that are noteworthy events.

Semitic and Turkic Periods

After the Aryan settlement, Kurdistan continued to receive new peoples and cultural influences, none however, strong enough to alter the Kurdish cultural and ethnic identity as did the Aryans. Large numbers of Aramaic-speaking people seem to have only settled in more accessible valleys of western Kurdistan. Through the introduction of Judaism, and later Christianity, some Kurds, however, came to relinquish Kurdish and spoke Aramaic instead despite the paucity of the Aramaic demographic element. It is fascinating to note through examining contemporary Kurdish culture that Judaism appear to have exercised a much deeper and more lasting influence on the Kurdish indigenous culture and religion than Christianity, despite the fact that most ethnic neighbors of the Kurds between 5th and 12th centuries were Christians.

The role of the Arabs and the impact of Islam on the Kurdish society and culture is less difficult to survey. The Arabian peninsula was experiencing a runaway population explosion when the advent of Islam translated that pressure into a massive outburst of Arabian nomads and brought about their settlement of foreign lands. In Kurdistan Arab tribes settled near almost every major town and agricultural center. By the 10th century, the Islamic historians and geographers report Arabian populations living among the Kurds from northern shores of Lake Van to Dinawar and from Hamadan to Malatya. These eventually assimilated, living behind only their genetic imprint (as the darker-complected city Kurds), and bequeathing of two exotic Semitic sounds into the speech of many Kurds: glottal a and h.

The same fleeting influence was true of the Turkic settlement of Kurdistan and its cultural impact. Several centuries of Turkic nomadic passage through Kurdistan beginning with the 12th century, wrecked havoc with the settled Kurds and their economy, as the Aryan migrations had done so 2500 years earlier. The Turkic cultural legacy was in itself nil, but the forces of internal change it unleashed within the Kurdish society turned out to be nearly as decisive as the Aryan invasion and settlement. Kurdistan would surely have turkified under this tremendous nomadic pressure and destructiveness, had it not been for one group of Kurdish nomads, the energetic Kurmanj, who emerged from the Hakkari highlands to fill nearly every niche left vacant by the agriculturist Kurds and less energetic nomads under the Turkic pressure. The Turkic nomads were primarily steppe nomads, and proved less of a match for the Kurmanj mountain nomads in the rough terrain of Kurdistan. Some Kurds were Turkified to be sure; e.g., the populous tribes of Dimbuli, Sheqaqi, Barani and Jewanshir. Conversely, many Kurdish tribes with Turkic names (e.g., Karachul, Chol, Oghaz, Jambul, Devalu, Ivä, Karaqich and Chichak) are in fact assimilated Turkish and Turcoman tribes who have left behind only their names and were in every other respect kurdicized.

This massive tribal dislocation that could have subsided over time took a new and more destructive turn by the advent of a century-long holocaust in Kurdish and Armenian territories in eastern Anatolia in the 16th century. The decisive turn for massive nomadization of the Kurdish was made by the long Perso-Ottoman wars and particularly the Safavids’ "scorched-earth" policy. More importantly still was the deadly economic blow brought about by the shift for the sea transport of the East-West commerce which also commenced at the turn of the 16th century. Together they heralded the beginning of the end for much of the social fabric and sophisticated culture of Kurdistan as it had existed since the time of the Medes. The agriculturist, urban-based Kurdish culture and society was to shift to a nomadic economy under a newly assumed identity. The nomadized Kurdish farmers eventually accepted the Shafiite Sunni Islam from the Kurmanj nomads and began speaking the vernacular of Kurmanji, a close kin to the old Pahlawani. In time, the older Kurdish society—religion and language notwithstanding—was marginalized and physically pushed to the peripheries of Kurdistan. At present, over three-quarters of the Kurds speak various dialects of Kurmanji and similar numbers practice Shafiite Sunni Islam. In a sense, the "Kurmanj" assimilated the "Kurds," and in the process they assumed the old ethnic name and inherited all that was left of the older culture. Until only 50 years ago, a vast majority of the "Kurds" would identify themselves as Kurmanj and their language as Kurmanji. It was the outsiders and the educated that continued to uniformly call them Kurds, regardless of the dialect they spoke, religion they practiced, or the economic life style they followed. In the past 50 years, however, the term Kurmanj as an ethnic designator has been ruthlessly suppressed by the native population themselves and their leadership in favor of the time-honored term, "Kurd." Only in the most remote areas in the mountains and the detached but populous Kurdish exclave in Khurasan and Turkmenistan is the term "Kurmanj" given routinely by the common people for their ethnic affiliation. This too is disappearing fast under the influence of the educated Kurds.

There is, as should be expected, a strong correlation between practice of ancient Yazdani religion and the speaking of Pahlawani, as there is also a close connection between being a Muslim and speaking Kurmanji. The shift from the former to the latter identity in Kurdistan is accelerating, and seems destined to totally submerge the residual Pahlawani-Yazdani identity of the older Kurdistan. Only a shrinking number of Kurds still speak Pahlawani in the form of the dialects of Dimili (Zaza) in far northwestern Kurdistan in Turkey, and as Gurani, Laki and Hewrami (Awramani) in southeastern Kurdistan in Iran and Iraq. The old religion of Yazdanism is still practiced as Alevism, Yezidism and Yarisanism (the Ahl-i Haqq) denominations, but these too are shrinking in number and import.

With introduction of modern age communication systems into the Kurdish society, the process of cultural and ethnic homogenization of the Kurds has inevitably accelerated. The last step in the evolution of Kurdish cultural and ethnic identity is near completion today. The Kurdish ethnic identity is thus destined to comprise Kurmanji-speaking, Shafiite Muslim people, the last layer to be added to the many former layers which, in combination, render the Kurds what and who they are today: the heirs to millennia of cultural and genetic evolution of the native inhabitants of the Zagros-Taurus mountain systems.

By Dr. Mehrdad R. Izady

History of the Kurds: Lecture 2

The Aryan Period

As early as 2000 BC, the vanguards of the Indo-European speaking tribal immigrants, such as the Hittites and the Mittanis (Sindis), had arrived in southwestern Asia. While the Hittites only marginally affected the mountain communities in Kurdistan, the Mittanis settled inside Kurdistan around modern Diyarbakir, and influenced the natives in several fields worthy of note, in particular the introduction of knotted rug weaving. Even rug designs introduced by the Mittanis and recognized by the replication in the Assyrian floor carvings, remain the hallmark of the Kurdish rugs and kelims. The modern mina khâni and chwar such styles are basically the same today as those the Assyrians copied and depicted nearly 3000 years ago.

The name ‘Mittani’ survives today in the Kurdish clans of Mattini and Motikan/Moti who inhabit the exact same geographical areas of Kurdistan as the ancient Mittani. The name "Mittan," however, is a Hurrian name rather than Aryan. At the onset of Aryan immigration into Kurdistan, only the aristocracy of the high-ranking warrior groups were Aryans, while the bulk of the people were still Hurrian in all manners. The Mittani aristocratic house almost certainly was from the immigrant Sindis, who survive today in the populous Kurdish clan of Sindi—again—in the same area where the Mittani kingdom once existed. These ancient Sindi seem to have been an Indic, and not Iranic group of people, and in fact a branch of the better known Sindis of India-Pakistan, that has imparted its name to the River Indus and in fact, India itself. (footnote 8 ) While the bulk of the Sindis moved on to India, some wondered into Kurdistan to give rise to the Mittani royal house and the modern Sindi Kurds. Others, still, remained in Europe, and are recorded in the 1st century AD inhabiting the Taiman Peninsula on the Sea of Azov between Russia and Ukraine.

Expectedly, the Mittani pantheon includes names like Indra, Varuna, Suriya and Nasatya is typically Indic. The Mittanis could have introduced during this early period some of the Indic/Vedic tradition that appears to be manifest in the Kurdish religion of Yazdanism.

The avalanche of the Indo-European tribes, however, was to come about 1200 BC, raining havoc on the economy and settled culture in the mountains and lowlands alike. The north was settled by the Haigs who are known to us now as the Armenians, while the rest of the mountains became targets of settlement of various Iranic peoples, such as the Medes, Persian, Scythians, Sarmatians, and Sagarthians (whose name survives in the name of the Zagros mountains).

By 850 BC, the last Hurrian states had been extinguished by the invading Aryans, whose sheer number of immigrants must have been considerable. These succeeded over time to change the Hurrian language(s) of the people in Kurdistan, as well as their genetic make-up. By about the 3rd century BC, the Aryanization of the mountain communities was virtually complete.

Since the star of the Mittani shown brightest in 1500 BC, Aryan dynasties of various size and influence continued their appearance in various corners of Kurdistan. None, however, was to match, and in fact surpass the Mittanis as the Medians. The rise of the Medes from their capital at Ecbatana (modern Hamadan) in 727 coincided with the fall of the last major Hurrian kingdom: the Mannaeans. Ignoring the proud legacy of the Hurrian states and even the Aryan empire of the Mittanis which can squarely be claimed by on every ground by modern Kurds, it is the Medes that the Kurds have grown most fund of. Medes are claimed regularly by the Kurds and pronounced by others to be the ancestors of them. This is strange, when realizing how many millennia of cultural and ethnic evolution preceded the rise of Medes into Kurdistan. In reality, Medes are no more the ancestors of the modern Kurds as all other Halafian, Hurrian and Mittani who came before them or the legion of other peoples and states that came after them. Nonetheless, today, even the first Kurdish satellite television transmitter is given the name "Med TV" (Kurdish for "Median TV"). Fascination of the Kurds with the Median Federation (a.k.a., Empire) that ended in 549 BC remains supreme, indeed.

It is surprising to most that among the Kurds the Aryan cultural was and still remains secondary to that of the Hurrians. Culturally, Aryan nomads brought very little with to add to what they found already present in the Zagros-Taurus region. As has been the case, cultural sophistication and civilization are not what nomads are known for. On the contrary, nomads are inclined to annihilate what settled life and culture they find in their path as adversaries for possession of land and political dominance. We have no ample evidence, including a bona fide economic dark age lasting for roughly 500 years in the areas touched by the Aryans, that they behaved much the same barbarian way.

The Aryan influence on the local Hurrian Kurdish people must have been very similar to what transpired in Anatolia 2,500 years later when the Turkic nomads broke in after the battle of Manzikert in AD 1071. Much insight can be learned from this more recent nomadic dislocation for the older, murkier Aryan episode. Following the Manzikert, the Turkic nomads gradually imparted their language to all the millions of civilized, sophisticated Anatolians whom they converted from Christianity to their own religion of Hanafi Sunni Islam. Almost everyone in Anatolia gradually assumed a new Turkish identity when converted to Islam. But, this did not mean that the old cultural, human and genetic legacy ceased to exist. On the contrary, the rich and ancient Anatolian cultures and peoples continued their existence under the new Turkish identity, albeit, with the addition of some genetic and cultural material brought over by the nomads.

Architecture, domestic and monumental, decorative arts, farming techniques, herding practices, and religion remained much the same in Kurdistan following Aryan settlement, while the people progressively came to speak the Indo-European, Iranic language of these Aryan immigrants, admit new deities into their earlier Hurrian pantheon, and become lighter in their complexion. No abrupt change is encountered in the culture of Kurdistan while this linguistic and genetic shift was taking place under the Aryan pressure, barring the appearance of the so-call, "gray ware" pottery.

Near every thing in the contemporary culture of the Kurds can be traced to this massive Hurrian substructure, with the Aryan superstructure generally quite superficial and "skin deep"—to use a pun, in many fundamental ways. Even the time-honored Kurdish tactic of guerrilla warfare finds its roots among the Hurrian Gutis long before its was put into good use as a well-tested and developed tactic by the Median Cyaxares in this Assyrian campaigns in 612 BC. In the Bisitun inscription, the Persian king Darius I also makes note of this battle tactic used by the mountaineers against his forces, calling the guerrillas the kara (a lexical cognate of the term, "guerrilla"). Eight hundred years later, King Ardasher, founder of the Persian Sasanian dynasty, faces the same defensive tactics by the Kurds. The term he uses for them is jan-spâr, which means almost identical with the modern term Kurds give their guerrilla warriors: the peshmerga.

So far the victory cylinder of the Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser I (r. 1114-1076 BC) is the oldest record of the incidence of the ethnic name of the Kurds. It records the "Kurti" or "Qurtie" among the peoples whom the king conquered in his mountain campaigns south of the Lake Van region. The more exact location of these "Kurti" is given by the same document as Mt. Azu/Hazu. We are extraordinarily lucky that this "address" was still current until about sixty years ago—over 3100 years after Tiglath-pileser I. The town of Kurti in the Mt. Hizan region south of Lake Van is the same as the "Kurti in the Mt. Azu" of the Assyrians. The town of Kurti was still serving as a seat of a Kurdish princely house when the Kurdish historian Sharaf al-Din Bitlisi added the dynasty’s history into his celebrated history, the Sharafnâma, in 1597. This "birthplace" of the Kurds continued to be known with the archaic name until the Turkish government changed its name and that of its eponymous river, respectively, to Aksar (at 38.30 N, 42.49 E) and Büyük river in the 1930s. The oldest Kurdish place name—its "birth place" thus joined history so recent in history.

The Akkadian term "Kurti" denoted vaguely and indeterminate portion or groups of inhabitants of the Zagros (and eastern Taurus) mountains. To their very end in the 6th century BC, on the other hand, the Babylonians loosely (and apparently pejoratively) called most every body who lived in the Zagros-Taurus system a "Guti", including the Medes! But Babylonian records also attest to many more specific subdivisional names such as the Mardi, Kardaka, Lullubi and Qardu, the last three of which have all been used frequently in the needless controversy over the roots and antiquity of the ethnic term ‘Kurd,’ and the question of the presence of a general ethnic designator.

By the 3rd century BC, at any rate, the very term Kurd (or rather "Kurti") had been conclusively established. Polybius (d. ca. 133 BC) in his history when reporting on the events of 221-220 BC, (footnote 9) and Strabo (d. ca. AD 48) in his geography (footnote 10) are the earliest Western sources I am aware of to have made mention of the Kurds with their present ethnic name, albeit, in latinized form Cyrtii, "the Kurti." Historians Livy, Pliny, Plutarch, and much later, Procopius also mention this ethnic name for the native population of Media and parts of Anatolia for the classical times. Ptolemy inadvertently provides us with an array of Kurdish tribal names, when he records them as they appear as toponyms for where the tribe resided. Bagraoandene for the Bagrawands or Bakrans of Diyarbakir, Belcanea for the Belikans of Antep, Tigranoandene for the Tirigans of Hakkari, Sophene for the Subhans of Elazig, Derzene for the Dersimis and Bokhtanoi for the Bokhti (Bohtans) etc. These tribes are still with us today.

When the Aryan Medes and Persians arrived on the eastern flanks of the Zagros around 1000 BC, a massive internal migration from the eastern Taurus and northern and central Zagros toward the southern Zagros was in progress. By the 6th century BC, many large tribes which we now find among the Kurds were also present in southern Zagros, in Fars and even Kirman. As early as the 3rd century BC, the "Kurtioi" are reported by the Greek, and later Roman authors (in the Latin form of "Cyrtii") to inhabit as much the southern Zagros (Persis or Pars/Fars) as the central and northern Zagros (Kurdistan proper). This was to continue for another millennium, by which time, the ethnic name of "Kurd" had become established for nearly all if not all inhabitants of the mountains, from the Straits of Hormuz to the heart of Anatolia. Northern Zagros and Anatolia once teamed with various and related groups of people speaking Iranic tongue(s). By about 2000 years ago, many of these, such as the Iranic Pontians, Commagenes, Cappadocians, the western Medes and the Indic Mitannis, like the earlier Hurrian Mannas, Lullus, Saubarus, Kardakas, and Qutils, had been totally absorbed into a new Kurdish ethnic pool. These are among many mountain-inhabiting peoples whose assimilation has formed genetically, culturally, socially and linguistically the contemporary Kurds. The Kurdish diversity of race, tradition and spoken dialects encountered today point to the direction of this compound identity.

Reflecting on the gradual and organic assimilation of one of these groups into the larger Kurdish ethnic pool, Pliny the Elder (d. AD 79) tries to reconcile what appeared to him to be rather a name-change for a familiar people. Enumerating the nations of the known world, he states, "Joining on to Adiabene [central Kurdistan centered on Arbil] are the people formerly called the Carduchi [the Kardukh] and now the Cordueni past whom flows the river Tigris…" (footnote 11)

These Carduchi mentioned by Pliny are the same people whom Xenophon and his fellow ten thousand Greek troops had encountered nearly three centuries earlier when retreating through Kurdistan in 401 BC. Xenophon called them the “Kardukhoi” The name is likely the same as that of ‘Kardaka,’ (the people who provided a part of the Babylonian royal guards before 530 bc), and the ‘Qarduim’ (mentioned frequently in the Talmud). (footnote 12)

The early Islamic sources enumerate tens of Kurdish tribes and family clans outside Kurdistan proper in the southern Zagros, the Caucasus, Elburz, Taurus and Amanus mountains. In time, however, all of these assimilated into the local. This fact has been an unwarranted source of puzzlement for many modern writers on Kurdish history. Unaware of the history and extent of early Kurdish migrations and finding, at present, very few Kurds in these other mountain areas, they have often drawn the wrong conclusion that the term "Kurd" could not have been an ethnic name but rather a designator for all mountain nomads in general. This facile hypothesis is hardly worthy of refutation, realizing that no such doubt is cast on any other mobile nations such as the Turks and that Arabs who have spread and contracted periodically over thousands of miles of territory. (footnote 13)

From the time the Kurds are Aryanized until the 16th century of our era, the Kurdish culture remained basically unchanged, despite introduction of new empires, religions, and immigrants. The Kurds remained primarily followers of the ancient, Hurrian religion of Yazdanism, spoke an Iranic language that the medieval Islamic sources termed Pahlawani. Pahlawani survives today in the dialects of Gurani and Dimili (Zaza) on the peripheries of Kurdistan. Only the loss of Kurds of the southern Zagros through their metamorphosis into Lurs and a fresh expansion of Kurds into Elbruz and Pontus mountains that are noteworthy events.

Semitic and Turkic Periods

After the Aryan settlement, Kurdistan continued to receive new peoples and cultural influences, none however, strong enough to alter the Kurdish cultural and ethnic identity as did the Aryans. Large numbers of Aramaic-speaking people seem to have only settled in more accessible valleys of western Kurdistan. Through the introduction of Judaism, and later Christianity, some Kurds, however, came to relinquish Kurdish and spoke Aramaic instead despite the paucity of the Aramaic demographic element. It is fascinating to note through examining contemporary Kurdish culture that Judaism appear to have exercised a much deeper and more lasting influence on the Kurdish indigenous culture and religion than Christianity, despite the fact that most ethnic neighbors of the Kurds between 5th and 12th centuries were Christians.

The role of the Arabs and the impact of Islam on the Kurdish society and culture is less difficult to survey. The Arabian peninsula was experiencing a runaway population explosion when the advent of Islam translated that pressure into a massive outburst of Arabian nomads and brought about their settlement of foreign lands. In Kurdistan Arab tribes settled near almost every major town and agricultural center. By the 10th century, the Islamic historians and geographers report Arabian populations living among the Kurds from northern shores of Lake Van to Dinawar and from Hamadan to Malatya. These eventually assimilated, living behind only their genetic imprint (as the darker-complected city Kurds), and bequeathing of two exotic Semitic sounds into the speech of many Kurds: glottal a and h.

The same fleeting influence was true of the Turkic settlement of Kurdistan and its cultural impact. Several centuries of Turkic nomadic passage through Kurdistan beginning with the 12th century, wrecked havoc with the settled Kurds and their economy, as the Aryan migrations had done so 2500 years earlier. The Turkic cultural legacy was in itself nil, but the forces of internal change it unleashed within the Kurdish society turned out to be nearly as decisive as the Aryan invasion and settlement. Kurdistan would surely have turkified under this tremendous nomadic pressure and destructiveness, had it not been for one group of Kurdish nomads, the energetic Kurmanj, who emerged from the Hakkari highlands to fill nearly every niche left vacant by the agriculturist Kurds and less energetic nomads under the Turkic pressure. The Turkic nomads were primarily steppe nomads, and proved less of a match for the Kurmanj mountain nomads in the rough terrain of Kurdistan. Some Kurds were Turkified to be sure; e.g., the populous tribes of Dimbuli, Sheqaqi, Barani and Jewanshir. Conversely, many Kurdish tribes with Turkic names (e.g., Karachul, Chol, Oghaz, Jambul, Devalu, Ivä, Karaqich and Chichak) are in fact assimilated Turkish and Turcoman tribes who have left behind only their names and were in every other respect kurdicized.

This massive tribal dislocation that could have subsided over time took a new and more destructive turn by the advent of a century-long holocaust in Kurdish and Armenian territories in eastern Anatolia in the 16th century. The decisive turn for massive nomadization of the Kurdish was made by the long Perso-Ottoman wars and particularly the Safavids’ "scorched-earth" policy. More importantly still was the deadly economic blow brought about by the shift for the sea transport of the East-West commerce which also commenced at the turn of the 16th century. Together they heralded the beginning of the end for much of the social fabric and sophisticated culture of Kurdistan as it had existed since the time of the Medes. The agriculturist, urban-based Kurdish culture and society was to shift to a nomadic economy under a newly assumed identity. The nomadized Kurdish farmers eventually accepted the Shafiite Sunni Islam from the Kurmanj nomads and began speaking the vernacular of Kurmanji, a close kin to the old Pahlawani. In time, the older Kurdish society—religion and language notwithstanding—was marginalized and physically pushed to the peripheries of Kurdistan. At present, over three-quarters of the Kurds speak various dialects of Kurmanji and similar numbers practice Shafiite Sunni Islam. In a sense, the "Kurmanj" assimilated the "Kurds," and in the process they assumed the old ethnic name and inherited all that was left of the older culture. Until only 50 years ago, a vast majority of the "Kurds" would identify themselves as Kurmanj and their language as Kurmanji. It was the outsiders and the educated that continued to uniformly call them Kurds, regardless of the dialect they spoke, religion they practiced, or the economic life style they followed. In the past 50 years, however, the term Kurmanj as an ethnic designator has been ruthlessly suppressed by the native population themselves and their leadership in favor of the time-honored term, "Kurd." Only in the most remote areas in the mountains and the detached but populous Kurdish exclave in Khurasan and Turkmenistan is the term "Kurmanj" given routinely by the common people for their ethnic affiliation. This too is disappearing fast under the influence of the educated Kurds.