Western Universalism - what's the big deal?

Re: Western Universalism - what's the big deal?

Should read:

https://eacpm.gov.in/wp-content/uploads ... 22_Nov.pdf

EAC-PM Working Paper Series EAC-PM/WP/06/2022

WHY INDIA DOES POORLY ON GLOBAL PERCEPTION INDICES

Case study of three opinion-based indices- Freedom in the World index, EIU Democracy index and Variety of Democracy indices

Why is it important? Ultimately these indices feed into credit ratings, investment decisions and so on.

The Press Information Bureau press release:

https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage ... ID=1878142

https://eacpm.gov.in/wp-content/uploads ... 22_Nov.pdf

EAC-PM Working Paper Series EAC-PM/WP/06/2022

WHY INDIA DOES POORLY ON GLOBAL PERCEPTION INDICES

Case study of three opinion-based indices- Freedom in the World index, EIU Democracy index and Variety of Democracy indices

Why is it important? Ultimately these indices feed into credit ratings, investment decisions and so on.

The Press Information Bureau press release:

https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage ... ID=1878142

Re: Western Universalism - what's the big deal?

even under the ambiguous title of the thread, this post would probably not pass muster, but i think it is an important piece of history and an insight into free will, societal pressures and mass manipulation by the govt for their own gain; in certain quarters, there is an apprehension that something akin to the below will be surreptitiously introduced to force the younger male generation to join the armed forces and boost record-low numbers

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_feather

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_feather

as an aside, congratulations to the thread to moving past another page...it only took about 5 years to achieve this result, is this the slowest "active" thread in brf history?At the start of World War I, Admiral Charles Fitzgerald, who was a strong advocate of conscription, wanted to increase the number of those enlisting in the armed forces. Therefore he organized on 30 August 1914 a group of thirty women in his home town of Folkestone to hand out white feathers to any men that were not in uniform. Fitzgerald believed using women to shame the men into enlisting would be the most effective method of encouraging enlistment.[5][6] The group that he founded (with prominent members being Emma Orczy and the prominent author Mary Augusta Ward) was known as the White Feather Brigade or the Order of the White Feather.[7]

Although the draft would conscript both sexes, only males would be on the front lines.[8][9][10][check quotation syntax] While the true effectiveness of the campaign is impossible to judge, it spread throughout several other nations in the empire. In Britain, it started to cause problems for the government when public servants and men in essential occupations came under pressure to enlist.

Anecdotes from the time indicate that the campaign was unpopular among soldiers, not least because soldiers who were home on leave could find themselves presented with feathers.

Supporters of the campaign were not easily put off. A woman who confronted a young man in a London park demanded to know why he was not in the army. "Because I am a German", he replied. He received a white feather anyway.[13]

Occasionally injured veterans were mistakenly targeted, such as Reuben W. Farrow who after being aggressively asked by a woman on a tram why he would not do his duty, turned around and showed his missing hand causing her to apologize.[7]

Perhaps the most misplaced use of a white feather was when one was presented to Seaman George Samson, who was on his way in civilian clothes to a public reception being held in his honour for having been awarded the Victoria Cross for gallantry in the Gallipoli campaign.[14]

The writer Compton Mackenzie, then a serving soldier, complained about the activities of the Order of the White Feather. He argued that "idiotic young women were using white feathers to get rid of boyfriends of whom they were tired".[16] The pacifist Fenner Brockway said he received so many white feathers that he had enough to make a fan.[17]

Re: Western Universalism - what's the big deal?

I was discussing the issue with a friend of mine, his wife and son, who are German (father is Indian origin, wife German)ricky_v wrote:even under the ambiguous title of the thread, this post would probably not pass muster, but i think it is an important piece of history and an insight into free will, societal pressures and mass manipulation by the govt for their own gain; in certain quarters, there is an apprehension that something akin to the below will be surreptitiously introduced to force the younger male generation to join the armed forces and boost record-low numbers

The son believed in conscription, because of the "danger" of Russia, he was very much in favour of it.

BUT ........he made it clear that he would leave rather than do it himself.

The problem with nations that have professional armies is that the common man thinks that war is some sort of camping expedition with nerf guns thrown in. When soldiers die the response is "well he chose to join!!"

Western militaries are in a recruitment crisis, because of all their previous wars and the utter incompetence of politicians they have ended in disaster. The list is long. It is all well and to talk about it, all you have to do nowadays to show how patriotic and gungho you are is to make war like comments on newspaper website comments sections. They dying and suffering is done by others.

Re: Western Universalism - what's the big deal?

Haresh wrote:...

this is a very prevalent mindset in fdf countries, no offense intended to your acquaintance, the othering, even othering of your own armed forces, i recall that there were many reddit threads (do not have the img or the url handy, sorry), where every wannabe war-monger, ironically socialist (unwittingly masquerading as communist) stated that in the communist world order, their role would be in committees of the commissar for reeducation, strategy and moral improvement, nobody ever volunteered for any practical role, not even as a farm digger.The son believed in conscription, because of the "danger" of Russia, he was very much in favour of it.

BUT ........he made it clear that he would leave rather than do it himself.

The problem with nations that have professional armies is that the common man thinks that war is some sort of camping expedition with nerf guns thrown in. When soldiers die the response is "well he chose to join!!"

The end goal of the soyboys is to roleplay with their funkopops all the military engagements and scholarly argue their findings and results with other soyboys, preferabbly online... so removed from the base of humanity rooted in animality, almost like a distinct subspecies that should never be able to procreate with the others, still human, atleast spiritually if not physically; a long time back, i stated that the armchair soyboys treated war as a board game, as a give and take between two players adhering by the same rules, a glorified cattle raid, all shts and giggles balanced on a weighing scale, and not the serious thing that it is, with grave consequences for every action, i still adhere to it, though global consensus has hardened in the favor of the frivolous /banal / trite, whatever you want to term it as, nature of conflict, with "yaaas-kween posting" on twitter replacing serious analyses

[/quote]Western militaries are in a recruitment crisis, because of all their previous wars and the utter incompetence of politicians they have ended in disaster. The list is long. It is all well and to talk about it, all you have to do nowadays to show how patriotic and gungho you are is to make war like comments on newspaper website comments sections. They dying and suffering is done by others.

there is another end of the spectrum as well, Haresh sir, again no handy images, though i did post in the understanding us thread, the yt video might have got punted due to the deteriorating public image of the actor in the videos of the army recruitment ad, the gist is:

1. why should i fight in a war 12 time zones away, when my own country is flooded with south americans, asians, africans, i want to fight for a homogeneous country not one based on civic nationalism

2. is there any benefit to the territorial integrity of my nation if i do participate in such a conflict by bumping off civilians of stand-by nations

3. why should i fight for the capitalistic gains of my overlords, in terms of resources, contracts... what do i, or my community gain from it?

4. the world has been harping on equality for many years now, well, equality is in terms of executing duties and not only in terms of profiting from rights, men, women, alt-women, they are all equal or so the state says, so why should i volunteer for any sacrifice, this is the current decade after all, such bigoted viewpoints hold no sway in modern society... the women usually become pregnant during times of conflict and spend time way from action, during regular seasons, it is back to reaping favoritism shown by the fdf

Re: Western Universalism - what's the big deal?

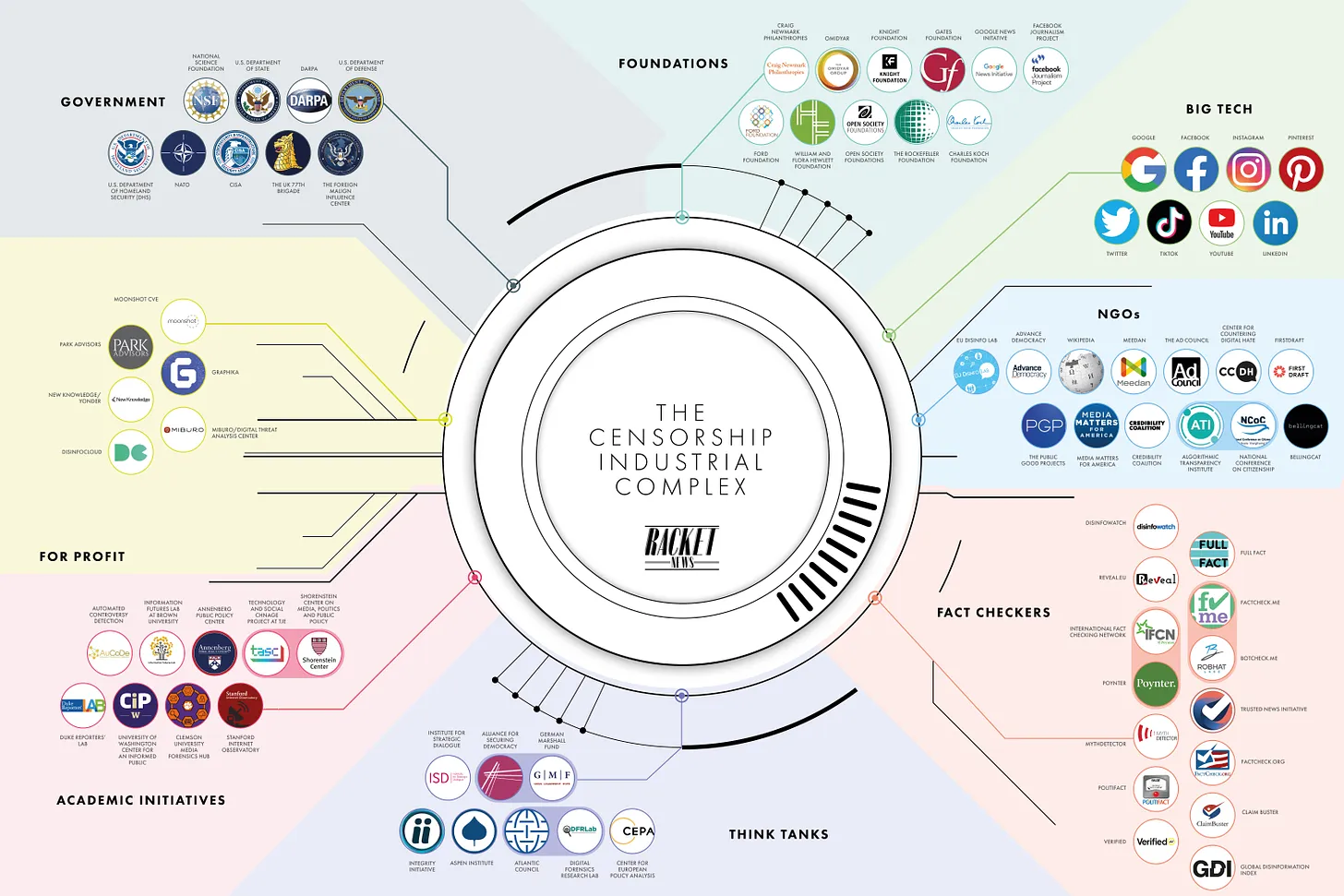

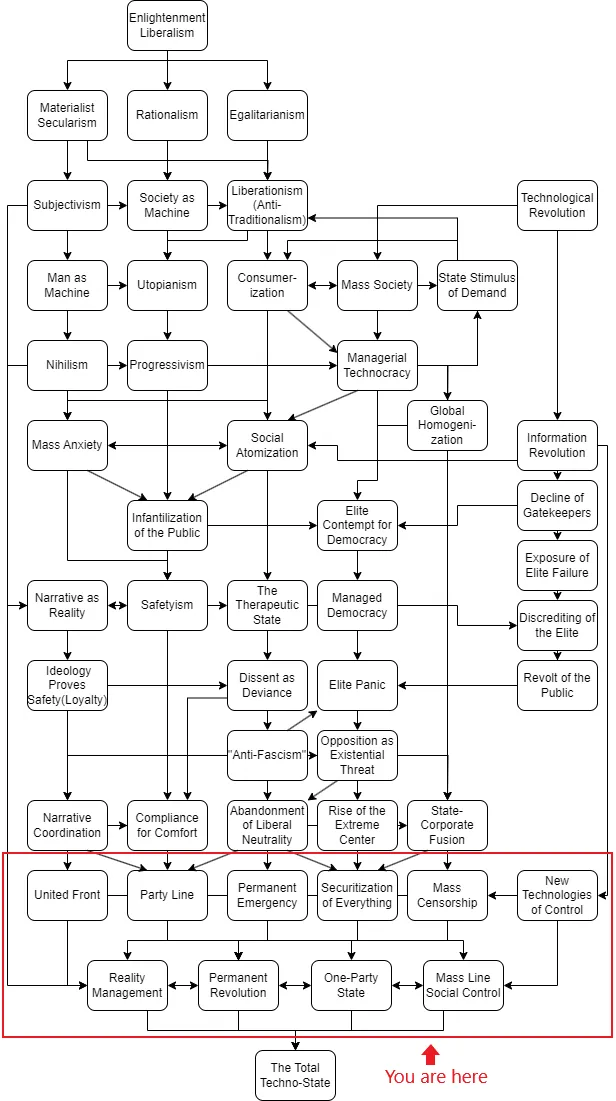

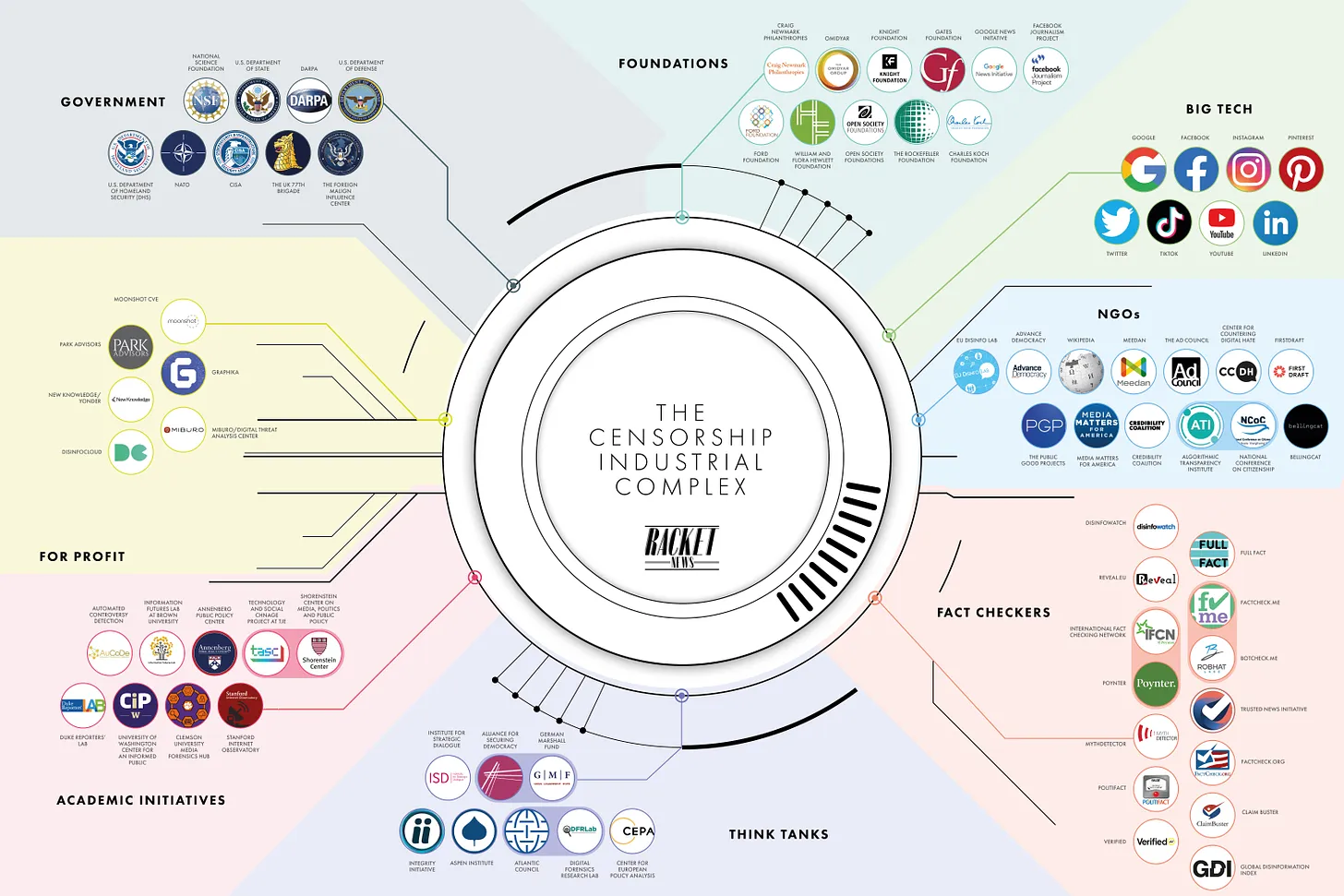

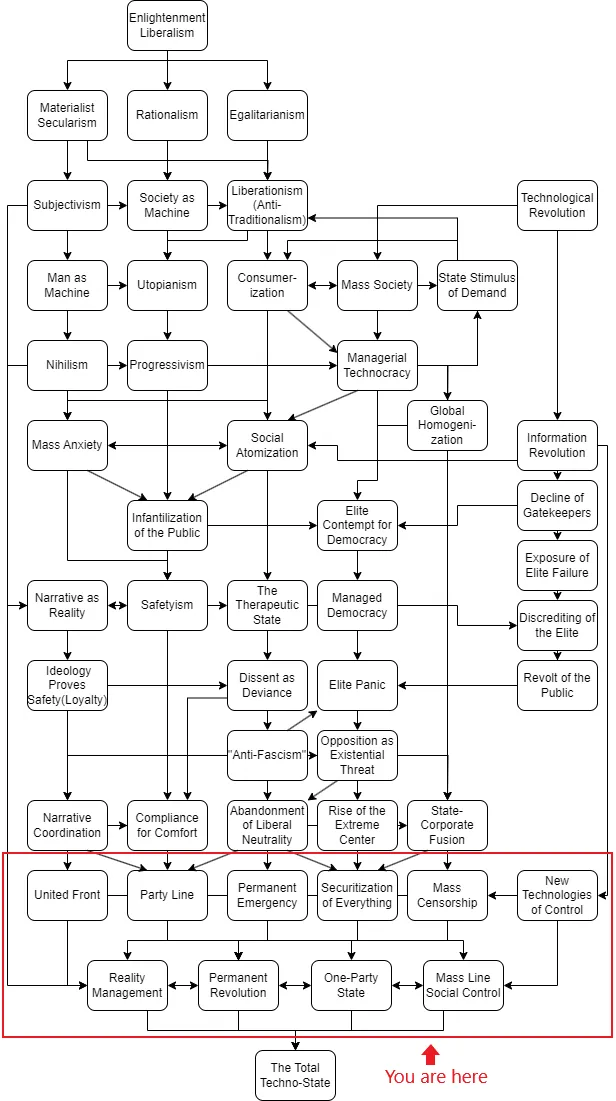

very intriguing image, highly dynamic with many options delineated on the matrix:

1) what future do you chose and why

2) what future do you think is the most probable and why

2) do we have an indic verison of this?

Re: Western Universalism - what's the big deal?

Waste of timericky_v wrote:

very intriguing image, highly dynamic with many options delineated on the matrix:

1) what future do you chose and why

2) what future do you think is the most probable and why

2) do we have an indic verison of this?

Re: Western Universalism - what's the big deal?

thank you for your one line contributionRoyG wrote: Waste of time

Re: Western Universalism - what's the big deal?

https://unherd.com/2023/06/will-america ... omes-fate/

The similar destinies of the United States and Rome can at times seem eerie. The three Punic Wars fought between the middle of the third century BC and the middle of the second century BC, constituted the great world wars of ancient Mediterranean civilisation, and ended with Rome’s complete destruction of Carthage. More recently, the two world wars of the 20th century ended with the complete destruction and defeat of Germany and Japan, and with the United States in a position of global dominance. In both conflicts, an empire’s supremacy reached its peak at the moment of victory.

Like the United States during the Second World War, Rome in the course of the Punic Wars became an empire. The First and Second Punic Wars saw Roman power established over Sicily, Sardinia and a good part of Spain — all former areas of Carthaginian influence. Rome also gradually extended its sway over greater Greece and Numidia, the latter coinciding with modern Algeria, to the west of Carthage on the North African coast.

Again, somewhat like the United States, imperialism helped lead to a dramatic increase in wealth in Rome itself, as a class of nouveau riche in the capital benefited from war booty, overseas trade, money lending and the like, according to the late British classicist S. A. Handford. Eventually, the Roman legions would evolve from a mass conscription military to a more professional, volunteer fighting force in order to regulate the vast territories under its influence as an imperial behemoth. The rough parallel with the development of the United States as a great power is hard to ignore, given how Washington itself has developed into a money-culture of well-heeled think tanks and flashy lobbyists, even as the mass conscription army that fought Second World War and Vietnam has morphed into a highly professional volunteer force of working-class youth, culturally divorced from the well-bred policy nomenklatura in the capital.

But the comparison becomes especially eerie when one considers that following the Punic Wars and Rome’s becoming an empire, it immersed itself in small wars against tribes and other chieftains that brought little glory and much political complications to Rome, and were a factor in its gradual decline.

In the oft-quoted words of the mid-20th century American theologian, Reinhold Niebuhr:

“The same strength which has extended our power beyond a continent has also interwoven our destiny with the destiny of many peoples and brought us into a vast web of history in which other wills, running in oblique or contrasting directions to our own, inevitably hinder or contradict what we most fervently desire.”

The young Winston Churchill was reading into the worst nightmare of Niebuhr’s and America’s imperial future when, in 1897, he described Afghanistan in The Story of the Malakand Field Force: “a roadless, broken and underdeveloped country; an absence of any strategic points; a well-armed enemy with great mobility and modern rifles, who adopts guerrilla tactics. The result… [is] that the troops can march anywhere, and do anything, except catch the enemy….

Subsidies and small expeditions? Now we are at a point of concision that defines the ancient Roman imperial past and the modern American one. Arguably the signature Roman imperial expedition, which vexed Rome and contributed to much political turmoil in the capital, was the so-called Jugurthine War, which lasted for seven years near the end of the second century BC. We owe our account of it to Sallust, who was born a few decades later in the first century BC, a time when this war fought by the Romans in Numidia against its king, Jugurtha, was still recent and presumably hotly debated. The geopolitics of the Jugurthine War were straightforward. Numidia, to the west of Carthage, had been an ally of Rome and their common hostility to Carthage had cemented their alliance. Yet, following Rome’s destruction of Carthage, Numidia suddenly no longer required Roman protection. That set the context for Numidia’s efforts at erasing Roman influence from its sprawling and difficult geography.

Jugurtha was a brilliant and devious king who fought against his adopted siblings over the spoils of Numidia, and bribed his way to victory time after time by his intrigues with Rome. He corrupted Rome and concomitantly gained power in Numidia. At first he was Rome’s ally. Then he became Rome’s enemy. By the time the Roman power structure realised he had to be destroyed it was too late to avoid a major war in a faraway territory. Sallust describes the war as “a hard-fought and bloody contest in which victories alternated with defeats”. The struggle, he goes on, “played havoc with all our institutions… For Jugurtha was so crafty, so well acquainted with the country, and so experienced in warfare, that one never knew what was the most deadly — his presence or his absence, his offers of peace or his threats of hostilities.”

There are shades of Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega, al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, and Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein in Jugurtha, in terms of the unconventional threat posed to Rome and the United States. In some cases the imperial power was ultimately victorious, as was Rome against Jugurtha; in some cases not. But the overall effect over time was to subtly and not so subtly weaken the empire.

the world we inhabit was created in 1945, the past history does not matter, but some in the establishment want to remake this world order in the image of their own demographicsThe problem is compounded by the nature of the foreign policy establishment in Washington, often disparaged as the “Blob”, because it often thinks according to a single, well-rehearsed mindset. The Blob wants to do great things in this world, because its heroes — those it particularly wants to emulate — were “present at the creation”, as the saying goes. I refer to the American inventors of the post-war order: men such as George Kennan, John McCloy, Averell Harriman, Dean Acheson and so on. The alliance structure that these men built would eventually, over the course of the decades, win the Cold War. The Blob wants to do something similar: create a new and long-lasting American order.

There is a pattern in all of this: great power wars strengthen a nation and relatively smaller expeditionary wars dissipate it. In our age, a small war means a professional military in fierce combat and a nation at the shopping mall, oblivious to what is going on overseas. When the population at home cannot relate to the fighting overseas, it is probably best if possible not to do it.

And yet, the Biden Administration is going beyond merely defending Ukraine and Taiwan with arms shipments. It is actually demanding that all countries in the world become democracies, something that the great secretaries of state of the late-Cold War Era, Henry Kissinger, George Shultz, and James Baker III, never would have done. Those diplomats were more interested in reconciliations than with issuing ultimatums. Issuing ideological ultimatums is a sign of decadence, that befits a country that is splitting at the seams politically and with an out-of-control national debt.

The Jugurthine War helped presage the end of the Roman Republic. Will America recover from the stain of its Middle East adventures? It’s an open question. Yet, great power rivalry that will likely continue for years, by engaging the whole society and economy, may change America in unpredictable ways, possibly leading to more political and social cohesion.

Re: Western Universalism - what's the big deal?

ricky_v wrote:https://unherd.com/2023/06/will-america ... omes-fate/

...........The similar destinies of the United States and Rome can at times seem eerie. The three Punic Wars fought between the middle of the third century BC and the middle of the second century BC, constituted the great world wars of ancient Mediterranean civilisation, and ended with Rome’s complete destruction of Carthage. More recently, the two world wars of the 20th century ended with the complete destruction and defeat of Germany and Japan, and with the United States in a position of global dominance. In both conflicts, an empire’s supremacy reached its peak at the moment of victory.

Subsidies and small expeditions? Now we are at a point of concision that defines the ancient Roman imperial past and the modern American one. Arguably the signature Roman imperial expedition, which vexed Rome and contributed to much political turmoil in the capital, was the so-called Jugurthine War, which lasted for seven years near the end of the second century BC. We owe our account of it to Sallust, who was born a few decades later in the first century BC, a time when this war fought by the Romans in Numidia against its king, Jugurtha, was still recent and presumably hotly debated. The geopolitics of the Jugurthine War were straightforward. Numidia, to the west of Carthage, had been an ally of Rome and their common hostility to Carthage had cemented their alliance. Yet, following Rome’s destruction of Carthage, Numidia suddenly no longer required Roman protection. That set the context for Numidia’s efforts at erasing Roman influence from its sprawling and difficult geography.

Jugurtha was a brilliant and devious king who fought against his adopted siblings over the spoils of Numidia, and bribed his way to victory time after time by his intrigues with Rome. He corrupted Rome and concomitantly gained power in Numidia. At first he was Rome’s ally. Then he became Rome’s enemy. By the time the Roman power structure realised he had to be destroyed it was too late to avoid a major war in a faraway territory. Sallust describes the war as “a hard-fought and bloody contest in which victories alternated with defeats”. The struggle, he goes on, “played havoc with all our institutions… For Jugurtha was so crafty, so well acquainted with the country, and so experienced in warfare, that one never knew what was the most deadly — his presence or his absence, his offers of peace or his threats of hostilities.”

There are shades of Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega, al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, and Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein in Jugurtha, in terms of the unconventional threat posed to Rome and the United States. In some cases the imperial power was ultimately victorious, as was Rome against Jugurtha; in some cases not. But the overall effect over time was to subtly and not so subtly weaken the empire.

[/quote]There is a pattern in all of this: great power wars strengthen a nation and relatively smaller expeditionary wars dissipate it. In our age, a small war means a professional military in fierce combat and a nation at the shopping mall, oblivious to what is going on overseas. When the population at home cannot relate to the fighting overseas, it is probably best if possible not to do it.

And yet, the Biden Administration is going beyond merely defending Ukraine and Taiwan with arms shipments. It is actually demanding that all countries in the world become democracies, something that the great secretaries of state of the late-Cold War Era, Henry Kissinger, George Shultz, and James Baker III, never would have done. Those diplomats were more interested in reconciliations than with issuing ultimatums. Issuing ideological ultimatums is a sign of decadence, that befits a country that is splitting at the seams politically and with an out-of-control national debt.

The Jugurthine War helped presage the end of the Roman Republic. Will America recover from the stain of its Middle East adventures? It’s an open question. Yet, great power rivalry that will likely continue for years, by engaging the whole society and economy, may change America in unpredictable ways, possibly leading to more political and social cohesion.

I think the above quote of equating Jugurtha with Manual Noriega, Saddam and Osama are misplaced as they while aligned with american interests briefly never held enough power or influence to shape American policy towards their own goals. All the three worthies should be replaced with China, that is at times in conflict with Amrican interests and at times aligned and most of the time seemd to influence American policy through bribes or lobbying as it is called now to help shore China's own interests.

Re: India-US relations: News and Discussions IV

Admin note: had warned you about not quoting long posts. Warning issued

Ricky_V,

I enjoyed reading your post. You’re going into territory which should be in Islam post.

One thing that is relevant to the this thread is the issue of servility which seems to have its origins in pre-Islamic beginnings of degeneration of Indian culture which later solidified with the persianized Islamic colonialism and reinforced with the British.

While we are chipping away at the colonized psyche, we still face an uphill battle with the more substantive issues. The Indo- US at first glance seems to be driven by China but I think it’s more than this. We have a problem with policymakers being tied to America through family, forced adoption of French enlightenment ideals and the democratic setup, the English apartheid state, and an anglicized civil service which largely escapes accountability by law. Despite cosmetic feel good symbolic gestures, these things remain intact.

My view is that China has been a mostly positive force for the world and India and has given us possibilities to piggyback partially on an emerging non-western framework. I think the time has come to rethink the state itself and whether it should be based on any sort of “ideals” which has been a western fashion for the past millennia. We perhaps start with the question - What comes naturally to us Indians?

Ricky_V,

I enjoyed reading your post. You’re going into territory which should be in Islam post.

One thing that is relevant to the this thread is the issue of servility which seems to have its origins in pre-Islamic beginnings of degeneration of Indian culture which later solidified with the persianized Islamic colonialism and reinforced with the British.

While we are chipping away at the colonized psyche, we still face an uphill battle with the more substantive issues. The Indo- US at first glance seems to be driven by China but I think it’s more than this. We have a problem with policymakers being tied to America through family, forced adoption of French enlightenment ideals and the democratic setup, the English apartheid state, and an anglicized civil service which largely escapes accountability by law. Despite cosmetic feel good symbolic gestures, these things remain intact.

My view is that China has been a mostly positive force for the world and India and has given us possibilities to piggyback partially on an emerging non-western framework. I think the time has come to rethink the state itself and whether it should be based on any sort of “ideals” which has been a western fashion for the past millennia. We perhaps start with the question - What comes naturally to us Indians?

Re: Western Universalism - what's the big deal?

x-posting from ind-us, psoting here instead of geopolitics thread as the topic is an overlap of current breakneck geopolitics and understanding the underlying reasoning including the historical motivations forming such moves

disha wrote:

It is inline with my expectation that US-India relations "are not just bullet points on a page". I posit that the global order has changed already and only two countries are capable to lead the world. US and India.

World is helped if both US and India work together for a better world future. Of course, for this US has to do more to get out of its self-centered Pax America policy and India (in general) has to be more confident about its role and responsibility. China does not matter, being a 1000lb self-centered gorilla, it has nothing to offer to the world other than strife, disease and cheap electronics.

Here is a thought exercise for the forum members, I state with complete confidence that the entire Asian identity, spanning from west Asia (not the middle-east/africa) and all the way to Japan is the result of Indic philosophy. What Asia thinks and behaves, except the colonial, islamic and the communist imprints, is basically rooted in Indic philosophy.

So if India is now responsible (uttardayitva) and rightful nation (uttaradhikari) to lead the world, the dayitva and adhikar has been handed to us by our ancestors tying us to the only unbroken human civilization on this Earth.*

1. US needs allies against China threat. Or does it need a frontline ally? Yes, China did a cardinal and strategic mistake of attacking its neighbour in the south twice and losing complete trust and respect. No different than the neighbour in north-west which is always tactically brilliant and strategically stupid.

Sullivan is in India this week for meetings with top Indian officials ahead of the Modi visit.

Modi’s visit comes as the Biden administration is working to deepen its relationship with countries that are crucial to counter what it sees as China’s growing threat. In deepening its ties with India the US has also appeared willing to overlook its democratic backsliding as it seeks to pull the South Asian nation away from Russia’s sphere of influence.

2. And it is interesting an article from a banana republic (US) is putting out "overlook its (India's) democratic backsliding" as if the later needs any approval card! Is the assertion a common edit from the editorial board of bloomberg?

One outcome that I am rooting for is for India to get enough cooperation from US to bolster its security, including defense & energy security and economy and deepening trade ties.Ties between US and India have grown stronger as concerns over China have increased despite significant differences “in the fields of values and vision,” said Sushant Singh, a senior fellow at New the Centre of Policy Research, a New Delhi-based think tank. “Those are currently being overridden by interests.”

The jet engine agreement, which would require technology transfer from America, will need approval from the US Congress, where India is banking on the general upswing in ties and bipartisan support to clear remaining hurdles.

Bengaluru-based Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd. and India’s Ministry of External Affairs didn’t immediately reply to requests for comment. The US National Security Council had no comment, and GE declined to comment.

The jet engine agreement would fit in with Modi’s wider push to boost defense manufacturing locally but with technology partnerships with nations that are keen to draw New Delhi into their orbit as Russia’s war in Ukraine drags on into a second year. Earlier this month Germany’s Thyssenkrupp AG’s marine arm and India’s Mazagon Dock Shipbuilders Ltd. signed an initial agreement to jointly build submarines for the Indian navy.

Russia remains India’s largest supplier of military hardware, though purchases have slowed by 19% in the last five years due to sanctions and increased competition from other manufacturing countries. Russian deliveries of military supplies to India have ground to a halt as the countries struggle to find a payment mechanism that doesn’t violate Western sanctions.

The domestic production of the GE engines will strengthen India’s fighter jet program and its air force, whose fleet of rapidly aging Russian fighters need to be replaced. It will also boost Modi’s image as he looks at a third term in office in national elections next year.

India and the US will also likely inch closer to agreements on other defense issues, including India’s purchase of over a dozen armed drones that could exponentially boost its sea and land defense capabilities.

...

--With assistance from Jennifer Jacobs and Ryan Beene.

* PS: If mods permit, I want to gather articles, information and evidences in a thread under "Indian Philosophy and how it molds the Asian identity". This thought was triggered by one-off statement by an ASI historian in a vlog and my visits to museums and seeing art & sculpture from Mongolia, S. Korea and Japan. And of course, the PM of Papua New-Guinea touching the feet of PM of India.

Re: Western Universalism - what's the big deal?

ricky_v wrote:apologies if off-topicdisha wrote: China does not matter, being a 1000lb self-centered gorilla, it has nothing to offer to the world other than strife, disease and cheap electronics.

imo, this view is incorrect, i have been looking at some of the videos of african and latin leaders with western broadcasters / officials, the view is always the same "you (the collective west) can only give lectures, china gives us infrastructure", that china gains through exorbitant rates and chinese companies is another matter, at the end of the day, these deprived nations get some much needed infra, whether it be power plants, dams, roads, bridges, airports, city infra ityadi, china, thus has heft and it would be unwise to broadly dismiss this outreach. These nations are also realising that though the west gave a lot of aid to them, this mostly went to chieftains, warlords who kept their nation in disarray for easier access to rare earths, the rest went to the ngos which very neatly operate out of any government jurisdiction (the assertion is not far-fetched, we all remember the halcyon days of the maino-led vaunted NAC). So, when the chinese show up and actually build something on the ground, it goes a long way in trust.

i disagree with assertion for you have not included the elephant.. or the lion in the room, persia / iran. Islam was spread by the arabic sword, yes, but it was nurtured and maintained by the persian philosophy / outlook and more chiefly by its bureaucrats / officials / vizier, i beleive there are many accounts of core arabs lamenting the persian involvement in governance during their "golden ages", also nowroz (inb4 navratri)Here is a thought exercise for the forum members, I state with complete confidence that the entire Asian identity, spanning from west Asia (not the middle-east/africa) and all the way to Japan is the result of Indic philosophy. What Asia thinks and behaves, except the colonial, islamic and the communist imprints, is basically rooted in Indic philosophy.

added later

; the prthus and parsus have been alien and distant ever since the days of the Dasarajanaya Yudhha and we have drifted apart much, persia was more molded by its conflicts with the Hellenistic worldview and the mideast including well into the balkans has a bedrock of both persian and hellenistic influences topped up by arabic, med, orthodox, turkic in varying proportions.

Now, the indic civilisation has also been influenced by the hellenstic outlook, yavanas have been a common feature in antiquity, and once their bloodlines intermingled with the hunas, sakas and kushanas, they were also major players in indic politics for some time, though this time the bedrock was indic...iow, if there are similarities, then it is a combination of outlook of pre-schism india and greek influence... and later with the mughals, but the layering is superficial, the meat of our philosophies are very different

all major civilisations have this 3-power phaseWorld is helped if both US and India work together for a better world future. Of course, for this US has to do more to get out of its self-centered Pax America policy and India (in general) has to be more confident about its role and responsibility., india (rashtrakutas, chalukyas, pala-pratihara), china (most of its history has this 3 power), europe and then the west, and this is the phase that the world is entering currently, imo, china supplies the hardware for the world (infra building), us supplies the software (institution building) as it wishes, india supplies it as it is (the rules based), there are always chances of a conflict in this matter

again, apologies for this ot post

Re: Western Universalism - what's the big deal?

RoyG wrote: Ricky_V,

I enjoyed reading your post. You’re going into territory which should be in Islam post.

One thing that is relevant to the this thread is the issue of servility which seems to have its origins in pre-Islamic beginnings of degeneration of Indian culture which later solidified with the persianized Islamic colonialism and reinforced with the British.

While we are chipping away at the colonized psyche, we still face an uphill battle with the more substantive issues. The Indo- US at first glance seems to be driven by China but I think it’s more than this. We have a problem with policymakers being tied to America through family, forced adoption of French enlightenment ideals and the democratic setup, the English apartheid state, and an anglicized civil service which largely escapes accountability by law. Despite cosmetic feel good symbolic gestures, these things remain intact.

My view is that China has been a mostly positive force for the world and India and has given us possibilities to piggyback partially on an emerging non-western framework. I think the time has come to rethink the state itself and whether it should be based on any sort of “ideals” which has been a western fashion for the past millennia. We perhaps start with the question - What comes naturally to us Indians?

Re: Western Universalism - what's the big deal?

on the question on the religious fervour and discipline in the west

1. background

when we compare the world systems, generally the count is at 5:

- judeo-christian

- islamic

- orthodox

- indic

- sinic

but i aver that the first 4 are very analogous, the only anomaly is the sininc civilisation.

When the persians first broke the covenant before the Dasarajanaya Yuddha, the main schism was between the proper place of the gods, which later morphed into polytheism in the indic east and monotheism in the persian west. This monotheism then travelled west and came in contact with the philosophies of egypt and mesopotamia to give rise to 3 (main) abrahamic religions; but as the main concept was of monotheism or at most the existence of a dualistic entity (good and bad), there could be only one ideology which was the truth, in this case, the others could not be incorporated for they were false and needed to be cleansed. This is the sharp contrast in the varying fortunes between the interaction of persia and hellenism and yavanas and indicism, which had its focus on polytheism and simply absorbed after lengthy philosophical debates any competing ideology within its broader framework.

persia and hellas were equally matched in the important tools of civilisation

- religious fervour

- cultural ritualism

- statecraft based on the above 2

in the end, both were exhausted, for they had existed as the opposite side of the same coin, but it is important to note that without their interaction, the abrahamic faiths would never have been formed as they were, and it is equally important to note that the cultural and spiritual heart of europe is in the far east because of these interactions. When the euros "pagan" religion was removed, it was this heartbeat that suffused every euro body and bid it ever closer to their spiritual homeland. The matters came to head during the crusades, when inhabitants of a land had to contest with the people of a faraway land, who had never been its inhabitants, but yet lay a claim to the place. When Protestanism was formed, it was an action against the prevailing order, a repudiation of the ancestral setup but yet within the framework of the broader concept, the fervours of which have now also diluted and extinguished.

2. how far do you see?

i have mentioned previously that the euros are an incomplete race, they require a periodic "chhabi" and only then will they clap and clangor with the most fearful poise; in contrast, persia, unable to defend its ideology with arms, seeped into its conquerors' ideology, modified it in accordance with their ancient outlook and solidified it with the civilisational ennui, not unlike the case with the chinese and their northern conquerors. The persians thus had religious fervour and cultural ritualism but no golem to apply to until the emergence of islam, the euros are another sort of golem but with sapped fervor and distaste towards any ritualism, always a different side of the same coin.

This combination is what i feel the current eu babucracy is working towards, in systemic thinking, they are currently riding in the regions of chaos, hoping to slingshot into a futuristic ummah / atheistic papacy with but civilisational vigour incorporating communal religiosity and ritualism (tending towards to a classic sinic setup but serving an empty throne), replacing the cultural heart outside of europe to form and function inside.

3. The anomaly

sinicism molded in its current state due to the chinese geographical location; misquoting, "the chini emperor wept for he had no more lands to conquer". The formation years of china were painful and bloody, but the ruling peasant elite went on an overdrive killing or driving away any who did not believe in the concept of wuxia, the hunas, sakas and kushanas were originally from now chinese lands and not just the periphery of the desert borderlands. So, once completed, discounting the warlike jurchen along the amur, and the jungles formed by the mekong, the chinese had conquered all "civilised areas". This is the primary reason for chinese outlook, very high on cultural ritualism, but very stated on religious fervour, an inward look with very little competing viewpoint, no gods to invoke to, only petitioning of ancestors.

1. background

when we compare the world systems, generally the count is at 5:

- judeo-christian

- islamic

- orthodox

- indic

- sinic

but i aver that the first 4 are very analogous, the only anomaly is the sininc civilisation.

When the persians first broke the covenant before the Dasarajanaya Yuddha, the main schism was between the proper place of the gods, which later morphed into polytheism in the indic east and monotheism in the persian west. This monotheism then travelled west and came in contact with the philosophies of egypt and mesopotamia to give rise to 3 (main) abrahamic religions; but as the main concept was of monotheism or at most the existence of a dualistic entity (good and bad), there could be only one ideology which was the truth, in this case, the others could not be incorporated for they were false and needed to be cleansed. This is the sharp contrast in the varying fortunes between the interaction of persia and hellenism and yavanas and indicism, which had its focus on polytheism and simply absorbed after lengthy philosophical debates any competing ideology within its broader framework.

persia and hellas were equally matched in the important tools of civilisation

- religious fervour

- cultural ritualism

- statecraft based on the above 2

in the end, both were exhausted, for they had existed as the opposite side of the same coin, but it is important to note that without their interaction, the abrahamic faiths would never have been formed as they were, and it is equally important to note that the cultural and spiritual heart of europe is in the far east because of these interactions. When the euros "pagan" religion was removed, it was this heartbeat that suffused every euro body and bid it ever closer to their spiritual homeland. The matters came to head during the crusades, when inhabitants of a land had to contest with the people of a faraway land, who had never been its inhabitants, but yet lay a claim to the place. When Protestanism was formed, it was an action against the prevailing order, a repudiation of the ancestral setup but yet within the framework of the broader concept, the fervours of which have now also diluted and extinguished.

2. how far do you see?

i have mentioned previously that the euros are an incomplete race, they require a periodic "chhabi" and only then will they clap and clangor with the most fearful poise; in contrast, persia, unable to defend its ideology with arms, seeped into its conquerors' ideology, modified it in accordance with their ancient outlook and solidified it with the civilisational ennui, not unlike the case with the chinese and their northern conquerors. The persians thus had religious fervour and cultural ritualism but no golem to apply to until the emergence of islam, the euros are another sort of golem but with sapped fervor and distaste towards any ritualism, always a different side of the same coin.

This combination is what i feel the current eu babucracy is working towards, in systemic thinking, they are currently riding in the regions of chaos, hoping to slingshot into a futuristic ummah / atheistic papacy with but civilisational vigour incorporating communal religiosity and ritualism (tending towards to a classic sinic setup but serving an empty throne), replacing the cultural heart outside of europe to form and function inside.

3. The anomaly

sinicism molded in its current state due to the chinese geographical location; misquoting, "the chini emperor wept for he had no more lands to conquer". The formation years of china were painful and bloody, but the ruling peasant elite went on an overdrive killing or driving away any who did not believe in the concept of wuxia, the hunas, sakas and kushanas were originally from now chinese lands and not just the periphery of the desert borderlands. So, once completed, discounting the warlike jurchen along the amur, and the jungles formed by the mekong, the chinese had conquered all "civilised areas". This is the primary reason for chinese outlook, very high on cultural ritualism, but very stated on religious fervour, an inward look with very little competing viewpoint, no gods to invoke to, only petitioning of ancestors.

Re: Western Universalism - what's the big deal?

Ricky,

Haven’t researched as much into Persians apart from the basic structure of its court but Hellenic civilizations collapsed because they couldn’t pick a dominant configuration of learning (plato vs bards).

This thread is ironic in the sense that everyone swears there is an alternative to western universalism, but there is no model which survives today to replace it.

More worrisome is that when you point out their logical inconsistencies and show how they are semites masquerading as Indians they become defensive and try to show how we indeed had things like democracy, human rights, feminism, etc since ancient times.

Haven’t researched as much into Persians apart from the basic structure of its court but Hellenic civilizations collapsed because they couldn’t pick a dominant configuration of learning (plato vs bards).

This thread is ironic in the sense that everyone swears there is an alternative to western universalism, but there is no model which survives today to replace it.

More worrisome is that when you point out their logical inconsistencies and show how they are semites masquerading as Indians they become defensive and try to show how we indeed had things like democracy, human rights, feminism, etc since ancient times.

Re: Western Universalism - what's the big deal?

this is an interesting line of thought, could you please expand on it?RoyG wrote:

Haven’t researched as much into Persians apart from the basic structure of its court but Hellenic civilizations collapsed because they couldn’t pick a dominant configuration of learning (plato vs bards).

RoyG ji, all good points raised in your 2 posts. I believe that the foundation myth of any nation is extremely vital in any state / civilisation, this was something that was understood from ancient days, and thus you have stories (factual or liberally stretched) for every civilisation: china had the foundation myth of black-haired locust like people petitioning higher powers (tianxia is still the dominant worldview), the current western foundation myth draws its power from post 1945 institution construction, drawing its power earliest by the explorations to the western hemisphere.RoyG wrote:

One thing that is relevant to the thread is the issue of servility which seems to have its origins in pre-Islamic beginnings of degeneration of Indian culture which later solidified with the persianized Islamic colonialism and reinforced with the British.

We have a problem with policymakers being tied to America through family, forced adoption of French enlightenment ideals and the democratic setup, the English apartheid state, and an anglicized civil service which largely escapes accountability by law. Despite cosmetic feel good symbolic gestures, these things remain intact.

This thread is ironic in the sense that everyone swears there is an alternative to western universalism, but there is no model which survives today to replace it.

I think the time has come to rethink the state itself and whether it should be based on any sort of “ideals” which has been a western fashion for the past millennia. We perhaps start with the question - What comes naturally to us Indians?

More worrisome is that when you point out their logical inconsistencies and show how they are semites masquerading as Indians they become defensive and try to show how we indeed had things like democracy, human rights, feminism, etc since ancient times.

The following article deals with the same topic, the mysteries of state foundations

https://lawliberty.org/book-review/the- ... foundings/

What does it take to found a new state? The abstract thought experiments of social theorizing tend to suggest a collective choice: a people deliberates, agrees on a social contract that best embodies its values, and then instantiates the appropriate social and institutional forms.

How exactly do people become “a people,” and what does it mean for them to choose together? How should they begin formal deliberations, given they are creating something new rather than operating under previously accepted rules? Why should the members of the group accept a particular leader to organize or preside over such deliberations?

Such questions create what Cornell political scientist Richard Bensel calls the “opening dilemma.” From a logical or legalistic perspective, Bensel argues that there can be no satisfactory answers to these conundrums. And yet, nation-states are founded. Leaders find ways to assume the mantle of the general will and simultaneously supply the people with an identity and a new state that will serve a “transcendent social purpose” integral to that identity. If they succeed at this task, which generally requires harnessing the masses’ emotions rather than satisfying any rigorous demands for reason or coherence, the leaders of the new state will simply bypass the practical difficulties that might otherwise be insurmountable. But to do this, they must use the cultural materials at hand. If the people lack a sense of unity, it is unlikely they can be talked into it. Offering an alien, artificial, or simply uninspiring purpose will leave them hopelessly mired in the opening dilemma.

Foundings are tightly tied up with revolutions—but Bensel makes it very clear that they are not simply two sides of the same coin. As he puts it, “A revolution decisively rejects the legitimacy of the ruling regime in the name of an alternative transcendent social purpose; a founding melds that purpose with a new state’s right to rule.”

Instead, the English people and the English constitutional monarchy grew up together, with moments like the adoption of Magna Carta simply affirming rights Englishmen regarded (even in 1215) as enduring from “time out of mind.” Even the Glorious Revolution emphasized continuity despite decisively establishing Parliament as the supreme authority in the state (with the concept of “the King-in-Parliament” smoothing over the conceptual disruption), so much so that that body “now sits as a constitutional convention whenever it convenes as a legislative body.” Parliament’s possession of overbearing formal authority, coupled with the English state’s dedication to protecting the historically-constituted rights of Englishmen, has peculiarly “elevated history to the position of guarantor” in English politics.

In each of these cases, the opponents of the old regime quickly discover that successfully toppling the old regime does not amount to establishing a legitimate state to take its place. Doing that requires grappling with who “the people” really are, and how the new government will live up to their aspirations. Bensel persuasively demonstrates that this next stage is not about aggregating values or polling the public to discern their wishes, because the very question of whose preferences should be treated as worthy is open to redefinition.

Both democratic and authoritarian states may rely on post-facto public ratification of founding decisions, but such events can make only a modest contribution to the essential ingredient: “a mythological conception of the will of the people, including a belief that that will can be revealed only through a properly conceived and performed political practice.” Any founding must be careful in how the public is asked to manifest its consent for the new regime, since agenda-setting and the determination of electoral qualifications are likely to predetermine the outcome. Both democrats and budding totalitarians want to harness the real will of the real people, as opposed to some counterfeit produced by misunderstanding or subversion, and both realize that voters, left to their own devices, will not arrive at satisfying institutional solutions.

What differentiates the two types of states, in Bensel’s view, is “the degree to which they insist on refining that will after the state has been founded.” The choice for ongoing democracy is, in part, an admission of imperfection on the part of democratic founders, who concede that the will of the people cannot be distilled so perfectly as to settle the important questions for all time. Consequently, the state must seek periodic direction from the people through elections, as imperfect as those may themselves be. Non-democratic founders, on the other hand, offer their people a truly transcendent vision of their place in history, which can only be realized by deference to the newly established authority, uniquely capable of serving the people’s true interests and fulfilling their destiny. Bensel claims that for both kinds of founders, the people’s imperfections necessitate a certain amount of benign manipulation. Going further, he rather startling observes, “It is just that some of these manipulations grate more harshly on our own Western sensibilities than others.”

Put another way: Bensel teaches us how the belief in a people’s “historic mission” can generate enough enthusiasm to get a founding over the hump, but he doesn’t much consider whether a sincere belief in such a mission will inevitably bring down states founded on this basis over the long run. He does give us a hint that this could be the case, observing that founders who espouse a world-historical mission are likely to see the states they are creating as inherently too modest vessels for the fulfillment of the people’s destiny, and therefore put a need for international expansion into the DNA of the new state.

Modern India has the societal mores of Victorian England, for that is when our foundation myth was created (though the constitution makers had the supreme foresight to start with "India that is Bharat"), so when we discuss issues of servility, otherness to the abrahamic invaders, imo, the dialogue is simply continuing from the Indian state of c.1909, or after the Morley Minto reforms; the makers made a constitution from their experiences beginning from that year till 1950, that is the oddness one would perceive in modern-day India; I do not mean to imply that the constitution is outdated and is not serving us well, but rather that the inherent defensiveness of the state is a self-imposed handicap of how the society viewed itself as a whole back then.Notwithstanding this downside of non-democratic foundings, in the book’s final paragraph Bensel raises a disturbing possibility: perhaps, in the contemporary world, it is only non-democratic founders who arm themselves with myths potent enough to overcome the opening dilemma. In democracies, meanwhile, “the entire apparatus of intellectual and scientific culture seems to be dedicated to exposing [myths and abstract beliefs] as fantasies,” which may mean that “we have exhausted this paradigm” in the modern world.

By closing with this foreboding, Bensel finally lets the normative camel get its nose under the tent. Perhaps democracies need to take the requirement of crafting their own mythologies more seriously—but our very reverence for the social scientific mindset and its demythologizing tendency could render that impossible. Given our limited ability to give our hearts over to new organizing principles, we ought to face up to the precariousness of democratic societies in the contemporary world—to realize that we need to conserve what we have, rather than fantasizing about modern refoundings of some sort. There is the disturbing possibility that, unlike our forebears, we would never make it out of the starting gate.

Re: Western Universalism - what's the big deal?

Ricky,

The foundations lie in SN Balagangadhara’s research program.

To begin to answer your first query some background is needed. On Hipkapi, there is a 1987 essay - Knowing to act and acting to know. You can also find some commentaries on it. The material is very dense and have some ideas and discoveries of my own. Perhaps, not to flood the thread we can talk about it outside brf if you’re interested. You can reach me - mail for nrg at gmail

The foundations lie in SN Balagangadhara’s research program.

To begin to answer your first query some background is needed. On Hipkapi, there is a 1987 essay - Knowing to act and acting to know. You can also find some commentaries on it. The material is very dense and have some ideas and discoveries of my own. Perhaps, not to flood the thread we can talk about it outside brf if you’re interested. You can reach me - mail for nrg at gmail

Re: Western Universalism - what's the big deal?

@RoyG ji, have mailed.

https://archive.is/EUcZT

https://archive.is/EUcZT

Whether we like it or not, we all live in the world the US has made.

Now, suffering from buyer’s remorse, it has decided to remake it. Janet Yellen, US Treasury secretary, outlined the economic aspects of the new US vision in a speech delivered on April 20. Seven days later, Jake Sullivan, the national security adviser to Joe Biden, gave an even broader, albeit complementary, speech on “Renewing American Economic Leadership”. It represented a repudiation of past policy.

More narrowly, the administration sees itself as confronting four huge challenges: the hollowing out of the industrial base; the rise of a geopolitical and security competitor; the accelerating climate crisis; and the impact of rising inequality on democracy itself.

In a key phrase, the response is to be “a foreign policy for the middle class”. What, then, is this supposed to mean?

First, a “modern American industrial strategy”, which supports sectors deemed “foundational to economic growth” and also “strategic from a national security perspective”. Second, co-operation “with our partners to ensure they are building capacity, resilience, and inclusiveness, too”. Third, “moving beyond traditional trade deals to innovative new international economic partnerships focused on the core challenges of our time”. This includes creating diversified and resilient supply chains, mobilising public and private investment for “the clean energy transition”, ensuring “trust, safety, and openness in our digital infrastructure”, stopping a race to the bottom in corporate taxation, enhancing protections for labour and the environment and tackling corruption.

Fourth, “mobilising trillions in investment into emerging economies”. Fifth, a plan to protect “foundational technologies with a small yard and high fence”. Thus: “We’ve implemented carefully tailored restrictions on the most advanced semiconductor technology exports to China. Those restrictions are premised on straightforward national security concerns. Key allies and partners have followed suit.” It also includes “enhancing the screening of foreign investments in critical areas relevant to national security”. These, Sullivan insists, are “tailored measures”, not a “technology blockade”.

Re: Western Universalism - what's the big deal?

Ricky,

You have mail. Thanks.

You have mail. Thanks.

Re: Western Universalism - what's the big deal?

https://theupheaval.substack.com/p/the- ... onvergence

This is the simple and easy narrative of our present moment. In some ways it is accurate: a geopolitical competition really is in the process of boiling over into open confrontation. But it’s also fundamentally shallow and misleading: when it comes to the most fundamental political questions, China and the United States are not diverging but converging to become more alike.

This elite obsession with control is accelerated by a belief in “scientific management,” or the ability to understand, organize, and run all the complex systems of society like a machine, through scientific principles and technologies. The expert knowledge of how to do so is considered the unique and proprietary possession of the elite vanguard.

Ideologically, this elite is deeply materialist, and openly hostile to organized religion, which inhibits and resists state control. They view human beings themselves as machines to be programmed, and, believing the common man to be an unpredictable creature too stupid, irrational, and violent to rule himself, they endeavor to steadily condition and replace him with a better model through engineering, whether social or biological.

Complex systems of surveillance, propaganda, and coercion are implemented to help firmly nudge (or shove) the common man into line. Communities and cultural traditions that resist this project are dismantled. Harmfully contrary ideas are systematically censored, lest they lead to dangerous exposure. Governing power has been steadily elevated, centralized, and distributed to a technocratic bureaucracy unconstrained by any accountability to the public.

The relentless political messaging and ideological narrative has come to suffuse every sphere of life, and dissent is policed. Culture is largely stagnant. Uprooted, corralled, and hounded, the people are atomized, and social trust is very low. Reality itself often feels obscured and uncertain. Demoralized, some gratefully accept any security offered by the state as a blessing. At the same time, many citizens automatically assume everything the regime says is a lie. Officialdom in general is a Kafkaesque tragi-comedy of the absurd, something only to be stoically endured by normal people. Yet year by year the pressure to conform only continues to be ratcheted higher…

And yet, I’m going to argue that commonalities are indeed growing, and that this is no illusion, coincidence, or conspiracy, but the product of the same deep systemic forces and underlying ideological roots. To claim that we’re the same as China, or even just that we’re turning into China (as I’ve admittedly implied with the title) would really just be political clickbait.

The reality is more complicated, but no less unsettling: both China and the West, in their own ways and at their own pace, but for the same reasons, are converging from different directions on the same point – the same not-yet-fully-realized system of totalizing techno-administrative governance. Though they remain different, theirs is no longer a difference of kind, only of degree. China is just already a bit further down the path towards the same future.

But how should we describe this form of government that has already begun to wrap its tentacles around the world today, including here in the United States? Many of us recognize by now that whatever it is we now live under, it sure isn’t “liberal democracy.” So what is it? To begin answering that, and to really explain the China Convergence, we’re going to need to start with a crash course on the rise and nature of the technocratic managerial regime in the West.

Part I: The Managerial Regime

Rapidly accelerating in the 20th century, the managerial revolution soon began to instigate another transformation of society in the West: it gave birth to a new managerial elite. A new social class had arisen out of the growing scale and complexity of mass organizations as those organizations began to find that, in order to function, they had to rely on large numbers of people who possessed the necessary highly technical and specialized cognitive skills and knowledge, including new techniques of organizational planning and management at scale. Such people became the professional managerial class, which quickly expanded to meet the growing demand for their services.

This did not mean, however, that the expansion of the new managerial order faced no resistance at all from the old order that it strangled. That previous order, which has been referred to by scholars of the managerial revolution as the bourgeois order, was represented not so much by the grande bourgeoisie (wealthy landed aristocrats and early capitalist industrialists) but by the petite bourgeoisie, or what could be described as the independent middle class.[2] The entrepreneurial small business owner, the multi-generational family shop owners, the small-scale farmer or landlord; the community religious or private educator; even the relatively well-to-do local doctor: these and others like them formed the backbone of a large social and economic class that found itself existentially at odds with the interests of the managerial revolution.

The animosity of this class struggle was accentuated by the particularly antagonistic ideology that coalesced as a unifying force for the managerial elite. While this managerial ideology, in its various flavors, presents itself in the lofty language of moral values, philosophical principles, and social goods, it just so happens to rationalize and justify the continual expansion of managerial control into all areas of state, economy, and culture, while elevating the managerial class to a position of not only utilitarian but moral superiority over the rest of society – and in particular over the middle and working classes. This helps serve as a rationale for the managerial elite’s legitimacy to rule, as well as an invaluable means to differentiate, unify, and coordinate the various branches of that elite.

But, in contrast to what was originally predicted by Marxists, these bourgeoisie came to be mortally threatened not from below by the laboring, landless proletariat, but from above, by the new order of the managerial elite and their expanding legions of paper-pushing professional revolutionaries. The clash between these classes, as the managerial order steadily encroached on, dismantled, and subsumed more and more of the middle class bourgeois order and its traditional culture, and the increasingly desperate backlash this process generated from its remnants, would come to define much of the political drama of the West. That drama continues in various forms to this day.

The animosity of this class struggle was accentuated by the particularly antagonistic ideology that coalesced as a unifying force for the managerial elite. While this managerial ideology, in its various flavors, presents itself in the lofty language of moral values, philosophical principles, and social goods, it just so happens to rationalize and justify the continual expansion of managerial control into all areas of state, economy, and culture, while elevating the managerial class to a position of not only utilitarian but moral superiority over the rest of society – and in particular over the middle and working classes. This helps serve as a rationale for the managerial elite’s legitimacy to rule, as well as an invaluable means to differentiate, unify, and coordinate the various branches of that elite.

Managerial ideology, a relatively straightforward descendant of the Enlightenment liberal-modernist project, is a formula that consists of several core beliefs, or what could be called core managerial values. At least in the West, these can be distilled into:

1. Technocratic Scientism: The belief that everything, including society and human nature, can and should be fully understood and controlled through scientific and technical means. In this view everything consists of systems, which operate, as in a machine, on the basis of scientific laws that can be rationally derived through reason. Humans and their behavior are the product of the systems in which they are embedded.

2. Utopianism: The belief that a perfect society is possible – in this case through the perfect application of perfect scientific and technical knowledge. The machine can ultimately be tuned to run flawlessly. At that point all will be completely provided for and therefore completely equal, and man himself will be entirely rational, fully free, and perfectly productive.

This state of perfection is the telos, or pre-destined end point, of human development (through science, physical and social). This creates the idea of progress, or of moving closer to this final end. Consequently history has a teleology: it bends towards utopia. This also means the future is necessarily always better than the past, as it is closer to utopia. History now takes on moral valence; to “go backwards” is immoral. Indeed even actively conserving the status quo is immoral; governance is only moral in so far as it affects change, thus moving us ever forwards, towards utopia.

3. Meliorism: The belief that all the flaws and conflicts of human society, and of human beings themselves, are problems that can and should be directly ameliorated by sufficient managerial technique. Poverty, war, disease, criminality, ignorance, suffering, unhappiness, death… none are examples of the human condition that will always be with us, but are all problems to be solved.

It is the role of the managerial elite to identify and solve such problems by applying their expert knowledge to improve human institutions and relationships, as well as the natural world. In the end there are no tradeoffs, only solutions.

4. Liberationism: The belief that individuals and society are held back from progress by the rules, restraints, relational bonds, historical communities, inherited traditions, and limiting institutions of the past, all of which are the chains of false authority from which we must be liberated so as to move forwards.

Old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits must all be dismantled in order to ameliorate human problems, as old systems and ways of life are necessarily ignorant, flawed, and oppressive. Newer – and therefore superior – scientific knowledge can re-design, from the ground up, new systems and ways of life that will function more efficiently and morally.

5. Hedonistic Materialism: The belief that complete human happiness and well-being fundamentally consists of and is achievable through the fulfillment of a sufficient number of material needs and psychological desires. The presence of any unfulfilled desire or discomfort indicates the systemic inefficiency of an un-provided good that can and should be met in order to move the human being closer to a perfected state.

Scientific management can and should therefore to the greatest extent possible maximize the fulfillment of desires. For the individual, consumption that alleviates desire is a moral act. In contrast, repression (including self-repression) of desires and their fulfillment stands in the way of human progress, and is immoral, signaling a need for managerial liberation.

6. Homogenizing Cosmopolitan Universalism: The belief that:

a) all human beings are fundamentally interchangeable and members of a single universal community;

b) that the systemic “best practices” discovered by scientific management are universally applicable in all places and for all people in all times, and that therefore the same optimal system should rationally prevail everywhere;

c) that, while perhaps quaint and entertaining, any non-superficial particularity or diversity of place, culture, custom, nation, or government structure anywhere is evidence of an inefficient failure to successfully converge on the ideal system; and

d) that any form of localism, particularism, or federalism is therefore not only inefficient and backwards but an obstacle to human progress and so is dangerous and immoral. Progress will always naturally entail centralization and homogenization.

7. Abstraction and Dematerialization: The belief, or more often the instinct, that abstract and virtual things are better than physical things, because the less tied to the messy physical world humans and their activities are, the more liberated and capable of pure intellectual rationality and uninhibited morality they will become.

Practically, dematerialization, such as through digitalization or financialization, is a potent solvent that can help burn away the repressive barriers created by attachments to the particularities of place and people, replacing them with the fluidity and universality of the cosmopolitan. Dematerialization makes property more easily tradable, and can more effectively produce homogenization and fulfill desires at scale. Indeed in theory dematerialization could allow almost everything to take on and be managed at vastly greater, even infinite, mass and scale, holding out the hope of total efficiency: a state of pure frictionlessness, in which change (progress) will be effortless and limitless. Finally, dematerialization also most broadly represents an ideological belief that it is the world that should conform to abstract theory, not theory that must conform to the world.

This managerial system developed into several overlapping, interlinked sectors that can be roughly divided into and categorized as: the managerial state, the managerial economy, the managerial intelligentsia, the managerial mass media, and managerial philanthropy. Each of these five sectors features its own slightly unique species of managerial elite, each with its own roles and interests. But each commonly acts out of its own interest to reinforce and protect the interests of the other sectors, and the system as a whole. All of the sectors are bound together by a shared interest in the expansion of technical and mass organizations, the proliferation of managers, and the marginalization of non-managerial elements.

The managerial state, characterized by its proliferating administrative bureaucracies and thirst for centralized technocratic control, has a strong incentive to launch utopian and meliorist schemes to “liberate” and reorganize more and more portions of society (the theoretical bases for which are pumped out by the managerial intelligentsia), necessitating entire new layers of bureaucratic management (and whole new categories of “experts”).

Meanwhile the managerial corporation also has a great deal to gain from the project of mass homogenization, which allows for greater scale and efficiencies (a Walmart in every town, a Starbucks on every corner, Netflix and Amazon accessible on the iPhone in every pocket) by breaking down the differentiations of the old order. The state, which fears and despises above all else the local control justified by differentiation, is happy to assist. The managerial economy also gains directly from the stimulation of greater consumer demand produced by the liberation of the masses from the repressive norms of the old bourgeois moral code and the encouragement of hedonistic alternatives – as thought up by the intelligentsia, advertised by the mass media, and legally facilitated by the state.

Mass media, too, has an interest in homogenization, allowing the entertainments and narratives it sells to scale and reach a larger and more uniform audience. Mass media, already an outgrowth of journalism’s integration with the mass corporation, also has an incentive to integrate itself with both the intelligentsia and the state in order to gain privileged access to information; the intelligentsia meanwhile relies of the media to affirm their prestige, while naturally the state has an incentive to fuse with the media to effectively distribute the chosen information and narratives it wants to reach the masses.

As the old bottom-up network of extended families, social associations, religious congregations, neighborhood charities, and other institutions of grass-roots bourgeois community life are broken down by the managerial system, managerial philanthropy – funded by the wealth produced by the managerial economy and offering the elite a means to transform that wealth into social power tax free – is eager to fill the void with a crude simulacrum, offering top-down philanthropic initiatives, managerial non-profit grifts, and astroturfed activist movements in their place.

These inevitably work to spread managerial ideology and the utopian social engineering campaigns of the state, further disrupting the bourgeois order. The breakdown of that order then inevitably only produces more social problems, which in turn provide new opportunities for managerial philanthropy to offer “solutions.”

The ideological pronouncements of the intelligentsia, transmitted to the public as revealed truth (e.g. “the Science”) by the managerial mass media, serve to normalize and justify the schemes of the state, which in turn gratefully supports the intelligentsia with public money and programs of mass public education, which funnel demand into the intelligentsia’s institutions and also help to fund the research and development of new technologies and organizational techniques that can further expand managerial control.

This served a straightforward purpose. Political theorists since Aristotle have recognized that “a numerous middle class which stands between the rich and the poor” is the natural bedrock of any stable republican system of government, resisting both domination by a plutocratic oligarchy and tyrannical revolutionary demands by the poorest. By eliminating this class, which had been the powerbase of his Nationalist rivals, Mao paved the way for his intelligentsia-led Marxist-Leninist revolution to dismantle every remaining vestige of republican government, replace the old elite with a new one, and take total control of Chinese society.

And yet – if you’ve been following along so far – China, with its vast techno-bureaucratic socialist state, is still recognizably a managerial regime. More precisely, China is a hard managerial regime.

Ever since the political philosopher James Burnham published his seminal book The Managerial Revolution in 1941, theorists of the managerial regime have noted strong underlying similarities between all of the major modern state systems that emerged in the 20th century, including the system of liberal-progressive administration as represented at the time by FDR’s America, the fascist system pioneered by Mussolini, and the communist system that first appeared in Russia and then spread to China and elsewhere. The thrust of all of these systems was fundamentally managerial in character. And yet each also immediately displayed some, uh, quite different behavior. This difference can, however, be largely explained if we distinguish between what the political theorist Sam Francis classified as soft and hard managerial regimes.

Part II: Making the Demos Safe for DemocracyThe character of the soft managerial regime is that described in the previous section. In contrast, a hard managerial regime differs somewhat in its mix of values. Hard managerial regimes tend to reject two of the seven values of the (soft) managerial ideology described above, discarding hedonism and cosmopolitanism (though homogenization and centralization remain a priority). Instead they tend to emphasize managing the unity of the collective (e.g. the volk, or “the people”) and the value that individual loyalty, strength, and self-sacrifice provides to that collective.[4]