New Delhi: On June 9, a day before “Ex Operation Malabar” by the navies of India, United States and Japan was set to kick off and the day deliberations over India’s bid to join the NSG were to take place in Vienna, China demonstrated its intent of claiming Arunachal Pradesh as its own by sending hundreds of its troops into East Kameng district.

Four days after the development, defence sources, admitting that a “transgression” had occurred, said it was a “temporary” one. The Army is soon expected to lodge a protest with Beijing. Defence sources also said such incursions in this sector were “not routine”.

Media reports said about 250 PLA soldiers spent nearly three hours in Indian territory before going back to the Chinese side.

Neutering & Defanging Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

http://www.deccanchronicle.com/nation/c ... roops.html

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

"Alas, China has managed to shatter that vision by continuing to behave, in relation to India, like an insensitive, intractable, impolitic, implacable dragon in the China shop. I have been disillusioned to the extent of being driven to ask myself whether all the effort that India has put in from the time of Nehru to be on its right side has been futile."salaam wrote:China drives India into the arms of the US

If the dimensions of the strategic partnership worked out by India and the US seem like a grand alliance targeted at you-know-who, China had better realise that it has fathered it,' says B S Raghavan, a long time observer of China.

Raghavan, the answer to your belabored quest is "yes" . You don't get accommodation from a position of weakness.

To quote JRRT/LOTR:

'Surety you crave! Sauron gives none. If you sue for his clemency you must first do his bidding. These are his terms. Take them or leave them!'

You don't nuzzle up to Smaug and suggest a division of the spoils.

Raghavan his IFS/IAS clique knackered Indian foreign policy to our detriment today. Now he wants to reluctantly embrace the US to stay relevant as a writer.

Oh please!

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

Chinese scholars may soon get India visa easily - Bharti Jain, ToI

India may soon remove China from the prior referral category (PRC) for issuing of research visas, according to sources in the home ministry. This will follow a similar concession announced recently for conference visas sought by Chinese citizens.

"We are actively considering a proposal to relax restrictions for issue of research visa to Chinese nationals. By removing China from the list of PRC countries as regards research visa, we seek to facilitate research projects/assignments of Chinese scholars on Indian soil as their applications will no longer be subjected to elaborate scrutiny by the security establishment prior to clearance," said a home ministry official.

Research visas are given to research professors or scholars and participants attending research conferences/seminars/workshops.

China has seen major relaxations in its visa regime with India under the Modi government. Modi had last year announced launch of e-tourist visa facility for Chinese citizens. Around a fortnight ago, India took off China from the list of PRC country as regards conference visa.

"PRC restrictions will still apply to Chinese citizens seeking business or employment visas, apart from certain categories of even conference and research visas," said an officer of the security establishment.

The easing of visa regime with China comes even as India is trying hard to secure membership of the nuclear suppliers group (NSG), but is wary of running into a Chinese wall. China had earlier opposed NSG waiver for India in 2008. For long, China has been bracketed with Pakistan, apart from stateless persons, under the restricted category for granting of visas, which necessitates prior security clearance based on inputs and verification by intelligence agencies.

Incidentally, Beijing is yet to reciprocate with similar relaxation in its visa norms for Indian citizens.{It continues to issue stapled visas}

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

The “Asian Space Race” and China’s solar system exploration: domestic and international rationales - Cody Knipfer, The Space Review

This lengthy article analyzes the reasons behind some of China's space projects.

This lengthy article analyzes the reasons behind some of China's space projects.

On April 22, the China National Space Administration announced its plan to launch a robotic Mars mission in 2020, to reach Mars by 2021. The project will involve an orbiter, a lander, and a rover. If successful, it will be China’s first visit to Mars and could mark the first Asian landing on the Red Planet, putting it in an elite group of nations that have successfully landed on the planet.

This announcement comes on the heels of a number of other Chinese space achievements and aligns with China’s other ambitious short-term space goals. In 2007 and 2010, China launched the lunar orbiters Chang’e 1 and 2. Chang’e 3, which launched, landed, and deployed a rover on the Moon’s surface in late 2013, was the first lunar soft-landing in 37 years as well as the first Asian soft-landing on the Moon.

Looking ahead at the next five years, China intends to conduct a lunar sample-return program with the lander Chang’e 5, expected to launch in 2017, and a potential Chang’e 6 mission in the early 2020s. Meanwhile, in 2018, Chang’e 4 will land on the lunar farside, the first surface exploration effort of its kind.

A common question for those studying, analyzing, and otherwise involved in space programs is that of rationale. Why do we go to space? What value do we derive from our activity, be it human or robotic, beyond the bounds of Earth? These questions go beyond the philosophical: their answers directly affect policy, planning, financing, and technological development.

Much has been made of the national security aspect of China’s space program, and for good reason: the dual-use nature of space assets and the strategic advantages of space supremacy are compelling to an increasingly assertive military power such as China. Yet unlike activity in Earth orbit, lunar and interplanetary exploration is of marginal direct national security value. Still, the Chinese government has evidently committed its political weight and financial resources to an ambitious, multi-element campaign of solar system exploration.

What motivates China’s robotic exploration aspirations? Moreover, what are the implications of those motivations for American policymakers? And more broadly, what does a “case study” of China’s efforts indicate about overall present-day rationales supporting a robotic exploration program?

Broad rationales for robotic exploration

Numerous rationales for space exploration have been issued and debated over the years. Of the more compelling arguments regarding what motivates policymakers to pursue a space program, those that highlight the prestige, national security, and geopolitical benefits are most supported by historical evidence.

Early rocketry was driven by the pursuit for ICBM capabilities. The international politics and competition of the Cold War were manifest in the Space Race, serving as leading rationales and motivations for the Apollo landings. The joint American-Soviet Apollo-Soyuz mission underscored a display of international cooperation and détente. National security rationales influenced the formulation of the Space Shuttle, a program intended in part to carry Defense Department satellites to orbit. The Soviet Buran project was a response to the shuttle, spurred by Soviet security concerns over American spaceplane capabilities. Space Station Freedom was in large part a prestige project, and the eventual cooption of Russia into the International Space Station was motivated by the national security desire to keep Russian engineers, technologies, and capabilities in “friendly” post-Soviet Russian hands.

These examples, of course, focus squarely on human spaceflight. What of robotic exploration? Non-human exploration through robotics is often seen as an “extension of human capabilities,” capable of engaging in research endeavors and pursuing a deeper understanding of the universe beyond the reach of a human presence. Accordingly, a principal motivation for robotic exploration is the pursuit of science and knowledge.

The endeavor of robotic exploration also reflects geopolitical interests and involves the pursuit of prestige, albeit with a lower profile than human missions. Discoveries and scientific breakthroughs are demonstrative of a country’s brain power, an element of its soft-power standing. Following the successful New Horizons mission to Pluto, for example, public commentators and NASA made note that the United States became the first country to visit every planet in the solar system. Arguably, Soviet and American robotic exploration post-Space Race was a “brain race,” a continuation of the technological competition and duel for soft-power influence that marked relations between the two countries throughout the Cold War. Notably, following the failure of their crewed heavy-lift N-1 rocket program, the Soviet response to the first Apollo missions was Luna 16, a robotic spacecraft that conducted a lunar sample return.

Drawing historical evidence from the Cold War era to argue that geopolitics and prestige were primary motivators of robotic exploration admittedly stands on shaky ground. Both the United States and the Soviet Union pursued human spaceflight in tandem with their robotic programs. Those campaigns of human spaceflight overshadowed robotic exploration as demonstrators of prestigious might and international superiority. Yet in the present day, the emerging space powers in Asia that lack an indigenous human spaceflight program—India, Japan, and South Korea—have evidently pursued and found robotic exploration as an equal substitute for displays of geopolitical strength and technological superiority. After all, as an “extension of human capabilities,” robotic exploration involves the elements of prestige and power that come associated.

As is increasingly apparent and as noted by multiple commentators and sources, a “space race,” involving significant competition through solar system exploration, is blossoming between these Asian space powers and China.

Today’s robotic space race

India became the first Asian power to successfully reach Mars orbit with its Mars Orbiter Mission, or Mangalyaan, probe in 2014. Looking to the future, India and France have signed a cooperative agreement for a joint mission involving a Mars orbiter in 2020, and have signaled that a Mars lander wouldn’t be far off. Meanwhile, India deployed the Chandrayaan 1 lunar orbiter and impactor in 2008 and has plans to launch Chandrayaan 2, featuring a lunar orbiter, lander, and rover, in late 2017.

Japan’s Hagoromo lunar orbiter, deployed in 1990, reached orbit but ceased transmitting enroute. The country’s SELENE orbiter and impactor, launched in 2007, was a success and Japan now has plans to land a rover on the Moon’s surface in 2018. Though the Nozomi spacecraft sent to Mars, launched in 1998, was a failure, Japan’s Aerospace Exploration Agency has been considering plans for a robotic sample-return mission to one of Mars’ moons in the early 2020s. Meanwhile, Japan has embarked on a successful campaign of asteroid exploration, with the Hayabusa spacecraft returning a sample of asteroid material in 2010 and the Hayabusa 2 spacecraft, launched in 2014, scheduled to return more asteroid material in 2020.

South Korea has its own Moon campaign, with hopes to reach the Moon with an orbiter by 2018. A subsequent Moon lander is planned for 2020 or sometime shortly thereafter. The lander phase of the program will correspond with the development of a new, heavier-lift South Korean launch vehicle.

Lending credence to the idea that these campaigns of robotic exploration constitute a “space race” is that these countries’ efforts, running simultaneous with each other, occur at a time of significant tension, conflict, and competition between them and China. Just as the Earthly politics of the Cold War influenced American and Soviet space policy and prompted rationales for programs, politics influence the current intent and aspirations of Asia’s space powers. China’s space efforts fit neatly and understandably within the emerging robotic space race.

The motivations of the geopolitical environment are of great significance for China’s space program, and to understand the domestic and international rationales behind China’s robotic exploration a brief discussion of China’s context is necessary.

China’s context

The People’s Republic of China is a rising global power seeking to establish political, military, and economic hegemony in the Asia-Pacific. The Chinese leadership is motivated by two principal concerns. First, the government is intent on asserting Chinese power, both hard and soft, to achieve those international aims. Second, as a single-party undemocratic state built upon the Chinese Communist Party’s legacy, the leadership seeks to tangibly demonstrate progress that resonates with the Party’s narrative of continual economic prosperity, scientific achievement, and national pride and unity so as to legitimize continued one-party rule.

Crucial among the Chinese Communist Party’s narrative is the legacy of “national humiliation” and the subsequent aspiration to achieve “great power” status. Drawing from the past half-century’s precedent of superpower capabilities, China’s leadership has concluded that, for China to be seen as a great power in the eyes of its own population, its neighbors, and the broader international community, the country must possess the features characteristic of one, such as an advanced technology sector, a force-projecting blue water navy, and a space program.

These motivations feed directly into the domestic and international rationales underlying China’s space efforts, including its robotic exploration of the solar system.

Domestic rationales

China’s space efforts and high-profile space activities, such as the Chang’e 3 lander and the upcoming plans for lunar sample return and a Mars rover, seek to tangibly and propagandistically validate the Chinese Communist Party’s legitimacy and entrench its hold on power. They are conducted to demonstrate that the Chinese Communist Party is the best provider of material benefits to the Chinese people and the best organization to propel China to its rightful place in world affairs.

A nation’s rhetoric is indicative of its rationales and motivations. Space missions are routinely described in the Chinese media and in government statements as advancing and enhancing China’s power and prestige, rousing national ethos, and inspiring people of all of China’s ethnic groups for “the socialist cause with Chinese characteristics.”

In its “Space Activities in 2011” white paper, the Chinese government laid out its rationale for actively pursuing a space program. The paper stated, “Space activities play an increasingly important role in China’s economic and social development. [Now is] a crucial period for China in building a moderately prosperous society, deepening reform and opening-up, and accelerating the transformation of the country’s pattern of economic development. China [pursues space] to meet the demands of economic development, scientific and technological development, national security and social progress; and to improve the scientific and cultural knowledge of the Chinese people, protect China’s national rights and interests, and build up its national comprehensive strength.”

In 2007, following the success of the Chang’e 1 orbiter, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao issued statements on behalf of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, the State Council, and the Central Military Commission (CMC), three leading organs of the Chinese government. He said that Chang’e 1 “demonstrates that our comprehensive national strength, our creative capabilities and the level of our science and technology continues to increase, with extremely important practical implications… for strengthening the force of our ethnic solidarity.”

During the landing of Chang’e 3, President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang were at the Beijing Aerospace Control Center to hear the mission declared a success. In a congratulatory message, the Communist Party’s Central Committee, State Council, and the Central Military Commission called the mission a “milestone in the development of China's space programs and a new glory in Chinese explorations.”

A commentary in the state-run Xinhua news agency opinioned that the success of Chang’e 3 was a realization of China’s space dream, “a source of national pride and inspiration for further development, [that makes] China stronger and will surely help realize the broader Chinese dream of national rejuvenation.”

In another Xinhua article, describing China’s Mars plans, a leading motivation for the upcoming mission is that “exploring the Red Planet and deep space will cement China’s scientific and technological expertise. The knock-on effect is that innovations and independent intellectual property rights will surge, and, as a result, China's core competence will increase, pushing development in other industries.”

This economic and scientific rationale is a key motivator for China’s robotic exploration program. As President Xi Jinping stated in a speech (note: link is in Chinese) to the Chinese Academy of Sciences in 2014, China is “closer than at any other time in its history of reaching its mighty goal of the rejuvenation of the Chinese people” and must “continue by resolutely implementing the strategy of using science and education to rejuvenate the country and innovation to drive development and unswervingly continue on the road of making China into a strong science and technology power.”

To that, the robotic lunar exploration program is a “major strategic decision by the Party Central Committee, State Council, and CMC taking a broad look at our country’s overall modernization and construction by grasping the world’s large science and technology events and promoting our country’s space enterprise development, promoting our country’s scientific and technological advancement and innovation, and improving our country’s comprehensive national power.”

China’s scientific exploration of the Moon has centered around the composition of the lunar surface. The country’s researchers are particularly interested in helium-3, with the hope that Chinese excavation of the material could eventually power a nuclear fusion reactor.

As can be seen in the Chinese rhetoric issued on its robotic exploration, China’s intent on becoming a “rejuvenated” and “great” power underlie these motivations. To that, they feed into the international rationales for Chinese exploration, as too does the geopolitical environment in which China currently exists.

In the words of the head of China’s first phase of lunar exploration, “Helium-3 is considered as a long-term, stable, safe, clean and cheap material for human beings to get nuclear energy through controllable nuclear fusion experiments. If we human beings can finally use such energy material to generate electricity, then China might need 10 tons of helium-3 every year.” More to the point, he continued with “the harvesting of Helium-3 on the Moon could start by 2025. Our lunar mining could be but a jumping off point for Helium 3 extraction from the atmospheres of our Solar System gas giants, Saturn and Jupiter.”

Clearly, a myriad of development, technological innovation, economic prosperity, and national pride rationales influence the Chinese government’s plans and aspirations for robotic exploration. As can be seen in the Chinese rhetoric issued on its robotic exploration, China’s intent on becoming a “rejuvenated” and “great” power underlie these motivations. To that, they feed into the international rationales for Chinese exploration, as too does the geopolitical environment in which China currently exists.

International rationales

China’s ambition for space achievement is driven by a belief that the technological, economic, and prestige benefits that result increase China’s national power, thereby enhancing China’s overall influence and giving China more freedom of action.

This is critical for China’s standing and position in the international community. China is pursuing hegemony in the Asia-Pacific, prompting major security concerns among its neighbors, but does so at its own risk: China’s neighbors are among its top trade partners, and are thereby responsible for China’s continued economic growth. This requires a delicate strategic balancing act in which China must minimize confrontation with potential foes and regional competitors, lest conflict undermine its critically important development goals and thereby sour the Communist Party’s legitimizing narrative, while at the same time strengthening economic ties with them. In turn, China’s neighbors are pursuing hedging strategies in which they strengthen security ties with China’s main military competitor—the United States—while continuing to seek beneficial economic arrangements with China.

In light of this strategic posturing, China’s hope is to arrive at a position of such eminence and clout through its economic dominance and soft-power influence that its neighbors simply defer to its wishes instead of confronting its rise. The successful execution of this strategy would avoid a regional or global conflict that would lay ruin to the interconnected and co-reliant economics of the Asia-Pacific. China’s pursuit of robotic exploration and the prestige of achievement is a method by which it seeks to arrive at that eminence.

Comments from leaders in China’s space sector and government reflect that intent. Ye Peijian of the Chinese Academy of Sciences wrote that, with China’s Mars mission, “we are not the first Asian nation to send a probe to Mars, [but] we want to start at a higher level.” Primer Wen Jaibao noted that Chang’e 1 was “raising our international standing.”

Space cooperation in the robotic sphere supports China’s goal of establishing a multipolar world, undermining the global unipolar hegemony currently enjoyed by the United States.

China’s neighbors, of course, understand the Chinese strategy and have thus pursued their own robotic exploration programs as a method to undermine China’s rising influence. Chinese achievement in space is less prestigious, and carries less weight in regional geopolitics, when its neighbors have succeeded with equivalent missions in a similar timeframe. Hence, the Asian space race.

It’s important to note that China’s rhetorical explanation for space exploration emphasizes its peaceful nature, an attempt to posture and portray the country as being on a “peaceful” rise, one which its neighbors should not fear. China’s 2011 space white paper notes that “China will work together with the international community to maintain a peaceful and clean outer space and endeavor to make new contributions to the lofty cause of promoting world peace and development.” Following Chang’e 3, President Xi Jinping noted that the mission was an “outstanding contribution of China in mankind’s peaceful use of space.”

Finally, there is an element of international cooperation within China’s robotic program that serves China’s purposes. While some commentators have rightly pointed out opportunities for deeper cooperation between China’s space agency and others (see “Time for fresh thinking about collaboration in space”, The Space Review, May 2, 2016), it is important to note that space cooperation does not drive relations on Earth but rather reflects them. The Apollo-Soyuz program, for example, was a result of increasing détente between the United States and the Soviet Union, not the catalyst. Nonetheless, space cooperation can strengthen China’s international position, increasing its influence among less developed countries and building China’s reputation as that of a reliable and attractive space partner.

To that end, space cooperation in the robotic sphere supports China’s goal of establishing a multipolar world, undermining the global unipolar hegemony currently enjoyed by the United States. In no position yet to compete with the United States for global hegemony, China hopes to arrive at a position of rough equality, or at least similar influence, in the international balance of power so as to shape and define it to fit its national interest.

As an example of this: China’s longest cooperative space relationship is with Russia and its predecessor, the Soviet Union. Notably, Russia in the present day is also seeking to disrupt the United States’ dominance of the global order through its actions in Eastern Europe and the Middle East. China has a long-term cooperation plan with Russia resulting in technology transfer, agreements, and cooperation on deep space exploration. China’s first attempt at a robotic Mars mission, the Yinghuo 1 orbiter, was launched attached to Russia’s Phobos-Grunt probe, which ended in failure. Even still, Russia is receptive to cooperating with China on the future exploration of the Moon and Mars.

Meanwhile, the European Space Agency and China have begun to seek out and identify areas in which the two can cooperate on future robotic space science missions and exploration.

These international rationales for robotic exploration, along with the domestic, drive Chinese space policy. China’s space policy, meanwhile, is an element of its broader policies and strategy for regional hegemony, “great power” status, and domestic development. For the United States—whose hegemony in the Asia-Pacific is at risk by China’s rise—the implications of China’s robotic exploration should be carefully considered. As with trade and economic policy and national security strategy, this consideration is necessary to develop policies that sustain and preserve the United States geopolitical leadership.

Implications for American policymakers

In China’s robotic exploration, three principal implications arise for American policymakers.

First, China’s campaign of solar system exploration is a reflection of its quest for domestic economic and technological development—facets of China’s pursuit of “great power” status—and should therefore be regarded as a metric to gauge China’s progress toward that status. China’s leadership has calculated that robotic exploration is one foundation by which to build the nation and has accordingly poured financial resources into that exploration. So long as China’s present-day strategy remains the country’s guiding plan, this robotic exploration will continue.

As such, changes in China’s intention for robotic exploration will indicate a change in Chinese grand strategy, signal a change in the rhetorical narrative underpinning the Communist Party’s legitimacy, or reflect a major downturn in the economic strength and technological capabilities supporting the Chinese effort. The particular details and ramifications of any of these changes have yet to reveal themselves, but would undoubtedly necessitate a major strategic reaction or shift by the United States.

Sino-American cooperation in robotic exploration may be one method by which the United States could to co-opt China’s rise and quest for influence.

Second, China’s campaign of solar system exploration is a reflection of its quest for international standing and regional influence. So long as that quest continues, so too should China’s robotic efforts. As such, so too will the competing space efforts of China’s wary neighbors. If the United States wishes to undermine China’s rise to regional hegemony, the opportunity to do so through heightened cooperation with or support for the space programs of U.S. Asian allies—Japan, India, and South Korea—presents itself as a strategically available and beneficial option.

Third, China’s campaign of solar system exploration involves elements of international cooperation which may undermine US leadership in space and, as a result, leadership on Earth. Countries not sharing the United States’ security concerns may turn to China as a partner with which to pursue space exploration. China may seek out avenues for cooperation with countries it is building relationships with, at the detriment to US influence with those countries. More importantly, one of the United States’ most established and prominent allies, the European Union, has sought deeper ties with China in space. Though international cooperation is space does not directly influence relations on Earth, this is a reflection of a gradually shifting balance of power where a multi-power world, in which multiple great powers with space exploration capabilities seek cooperation with each other, is emerging from the current one dominated by United States technological and geopolitical hegemony.

This point invariably prompts discussions of Sino-American cooperation in space exploration. That is too broad a discussion, with too many positives and negatives in favor of and opposed to the idea, for the scope of this essay. Nonetheless, the rationales behind China’s exploration program will motivate any change in current law preventing cooperation in space between the United States in China or lend credence to the preservation of the legal status quo.

It is the opinion of the author, however, that Sino-American cooperation in robotic exploration may be one method by which the United States could to co-opt China’s rise and quest for influence. China will invariably pursue solar system exploration for its national interest; without the opportunity for cooperation with China in space exploration, the United States stands by idly as the Chinese pursue other partners and objectives at the detriment to American global influence. If the Chinese are seeking to rise in the international system so as to change it and are doing so in part through solar system exploration, it may be wise strategy for the United States to cooperate with—and co-opt—the Chinese in order to preserve the American national interest and international status quo to the greatest extent possible.

China as a case study

Though the domestic and international context supporting them are unique to the country, China’s rationales for robotic exploration are indicative of the present-day motivations for programs of solar system exploration.

Whereas the rationale for human spaceflight in the 1960s and early 1970s was to win a space race, so too is the rationale for robotic spaceflight in the 2010s and beyond.

Robotic exploration goes beyond the pursuit of science and knowledge, though those are key goals for and benefits derived from such exploration. It directly connects to a country’s goals of economic and technological development, national pride, and international influence and clout. To that end, robotic exploration supports a country’s broad grand strategy—its geopolitical posturing and domestic planning.

For countries that lack programs of human exploration, robotic missions serve as equivalent substitutes through which they derive the prestige and political benefits that manned spaceflight provides. India, Japan, and South Korea have pursued relatively ambitious programs of robotic exploration at least in part to compete with China, just as the Soviet Union and the United States pursued human spaceflight and human Moon missions to compete with each other.

To that end: some have argued that the United States and China are not nor will be in a space race. It is true that the United States and China will likely not be locked in competition for equal achievement and prominence in human spaceflight; the United States remains the predominant spacefaring country in the world. Yet the thesis of those arguments miss the mark: more than just competition in space, a space race is an element of broader geopolitical competition, such as what the United States and China—and India, Japan, South Korea, and China—now find themselves in. So long as geopolitical tensions and shifts to the regional and global balance of power continue, so too will these countries find themselves racing in space to support and satisfy their race on Earth. Whereas the rationale for human spaceflight in the 1960s and early 1970s was to win a space race, so too is the rationale for robotic spaceflight in the 2010s and beyond.

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

Malabar 2016: Chinese spy ship shadows Indian, US, Japanese naval drill in the Western Pacific - Reuters

A Chinese observation ship shadowed the powerful US aircraft carrier, John C. Stennis, in the Western Pacific on Wednesday, a Japanese official said, joining warships from Japan and India in drills close to waters Beijing considers its backyard.

The show of American naval power comes as Japan and the United States worry Beijing will look to extend its influence into the Western Pacific with submarines and surface vessels as it pushes its territorial claims in the neighbouring South China Sea.

Beijing views access to the Pacific as vital both as a supply line to the rest of the world's oceans and for the projection of its naval power.

The 100,000 ton Stennis, which carries F-18 fighter jets, joined nine other naval ships including a Japanese helicopter carrier and Indian frigates in seas off the Japanese Okinawan island chain. Sub-hunting patrol planes launched from bases in Japan are also participating in the joint annual exercise dubbed Malabar.

The Stennis, which has been followed by the Chinese ship since patrolling in the South China Sea, will sail apart from the other ships, acting as a "decoy" to draw it away from the eight-day naval exercise, a Japanese Maritime Self Defense Force officer said, declining to be identified because he was not authorized to talk to the media.

Blocking China's unfettered access to the Western Pacific are the 200 islands stretching from Japan's main islands through the East China Sea to within 100 kilometres of Taiwan. Japan is fortifying those islands with radar stations and anti-ship missile batteries.

By joining the drill Japan is deepening alliances it hopes will help counter growing Chinese power. Tensions between Beijing and Tokyo recently jumped after a Chinese warship for the first time sailed within 24 miles (38 km) of contested islands in the East China Sea.

The outcrops known as the Senkaku in Japan and the Diaoyu in China lie 220 km (137 miles) northeast of Taiwan.

Wary of China's more assertive maritime role in the region, the US Navy's Third Fleet plans to send more ships to East Asia to work alongside the Japan-based Seventh Fleet, a US official said on Tuesday.

For India, the gathering is an chance to put on a show of force close to China's eastern seaboard and signal its displeasure at increased Chinese naval activity in the Indian Ocean. India sent its naval contingent of four ships on a tour through the South China Sea with stops in the Philippines and Vietnam on their way to the exercise. {In a few years' time, Philippines & Vietnam would also be part of Ex. Malabar}

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

Article XXI

How do the efforts to liberalise trade square with the provisions under Article XXI that allow a country to impose sanctions, and hence restrict trade, in order to ensure its national security interests? The short answer to this would simply be that they don’t. The reality, however, is somewhat more complex.

http://www.worlddialogue.org/content.php?id=100

Economic Sanctions and the WTO

What does Article XXI on security exceptions say? It states that

Nothing in this Agreement shall be construed

(a) to require any contracting party to furnish any information the disclosure of which it considers contrary to its essential security interests; or

(b) to prevent any contracting party from taking any action which it considers necessary for the protection of its essential security interests

(i) relating to fissionable materials or the materials from which they are derived;

(ii) relating to the traffic in arms, ammunition and implements of war and to such traffic in other goods and materials as is carried on directly or indirectly for the purpose of supplying a military establishment;

(iii) taken in time of war or other emergency in international relations; or

(c) to prevent any contracting party from taking any action in pursuance of its obligations under the United Nations Charter for the maintenance of international peace and security.

The WTO provisions in Article XXI thus entitle a member to interrupt its trade relations immediately, without prior notice and without leaving much room for the target country to dispute the measures under the relevant dispute settlement procedures.

http://www.wl-tradelaw.com/wto-rules-an ... ian-trade/

s drafted, the Security Exceptions in Article XXI(b) and (c) are qualified. Article XXI(b) allows a WTO member to take any action which it considers necessary for the protection of its essential security interests relating to fissionable materials or the materials from which they are derived; relating to traffic in arms, ammunition and implements of war and to such traffic in other goods and materials as is carried on directly or indirectly for the purpose of supplying a military or other establishment; and taken in time of war or other emergency in international relations. Article XXI(c) allows a WTO Member to take any action in pursuance of its obligations under the United Nations Charter for the maintenance of international peace and security. Although these exceptions are qualified, many have taken the view that WTO Members have an absolute right to rely on the Security Exceptions to justify any action that violates WTO obligations.

https://www.uni-trier.de/fileadmin/fb5/ ... huetzt.pdf

Is on the point that China cannot do much if we show them the middle finger and ban their imports

https://books.google.co.in/books?id=g-u ... ns&f=false

Another link on similar issues

How do the efforts to liberalise trade square with the provisions under Article XXI that allow a country to impose sanctions, and hence restrict trade, in order to ensure its national security interests? The short answer to this would simply be that they don’t. The reality, however, is somewhat more complex.

http://www.worlddialogue.org/content.php?id=100

Economic Sanctions and the WTO

What does Article XXI on security exceptions say? It states that

Nothing in this Agreement shall be construed

(a) to require any contracting party to furnish any information the disclosure of which it considers contrary to its essential security interests; or

(b) to prevent any contracting party from taking any action which it considers necessary for the protection of its essential security interests

(i) relating to fissionable materials or the materials from which they are derived;

(ii) relating to the traffic in arms, ammunition and implements of war and to such traffic in other goods and materials as is carried on directly or indirectly for the purpose of supplying a military establishment;

(iii) taken in time of war or other emergency in international relations; or

(c) to prevent any contracting party from taking any action in pursuance of its obligations under the United Nations Charter for the maintenance of international peace and security.

The WTO provisions in Article XXI thus entitle a member to interrupt its trade relations immediately, without prior notice and without leaving much room for the target country to dispute the measures under the relevant dispute settlement procedures.

http://www.wl-tradelaw.com/wto-rules-an ... ian-trade/

s drafted, the Security Exceptions in Article XXI(b) and (c) are qualified. Article XXI(b) allows a WTO member to take any action which it considers necessary for the protection of its essential security interests relating to fissionable materials or the materials from which they are derived; relating to traffic in arms, ammunition and implements of war and to such traffic in other goods and materials as is carried on directly or indirectly for the purpose of supplying a military or other establishment; and taken in time of war or other emergency in international relations. Article XXI(c) allows a WTO Member to take any action in pursuance of its obligations under the United Nations Charter for the maintenance of international peace and security. Although these exceptions are qualified, many have taken the view that WTO Members have an absolute right to rely on the Security Exceptions to justify any action that violates WTO obligations.

https://www.uni-trier.de/fileadmin/fb5/ ... huetzt.pdf

Is on the point that China cannot do much if we show them the middle finger and ban their imports

https://books.google.co.in/books?id=g-u ... ns&f=false

Another link on similar issues

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

No incursion into Arunachal Pradesh; it is our land: China - PTI

China today rejected allegation of incursion by its troops in Arunachal Pradesh, saying the Sino-India border has not yet been demarcated and the soldiers of the People's Liberation Army were conducting "normal patrols" on the Chinese side of the Line of Actual Control.

"China and India border has not yet been demarcated," Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman, Lu Kang told media briefing here answering a question of reports of 250 Chinese troops entering Yangste, East Kameng district on June 9.

"It is learnt that China's border troops were conducting normal patrols on the Chinese side of the LAC (Line of Actual Control)," Lu said.

The big contingent of PLA soldiers stayed in the area for few hours and left for their base, the reports said.{I hope the Indian Army reciprocates such behaviour.}

The incursion into Arunachal Pradesh came at a time when China is opposing India's entry into the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) on the ground that India has not signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

Beijing, which is reportedly backing Pakistan's application into the 48-member nuclear club controlling the nuclear commerce, is calling for consensus about admission of the new members.

On the issue of incursions, China has been maintaining the same stand whenever its troops crossed into the Indian side of the LAC stating that both countries have difference perception about it.

While both sides in recent years managed to reduce tensions between the troops patrolling the disputed areas with various mechanismS, China has not responded positively to India's proposal to demarcate the 3,488 km of the LAC to avoid border tensions.

The two countries have so far held 19 rounds of boundary talks by Special Representatives. {I think we should show no interest in these useless boundary talks, citing Chinese incursions}

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

China shaken of US, India, Japan triumvirate: Chinese spy ship sneaks into Japanese territorial waters tracking Indian ships - PTI

TOKYO: A Chinese navy spy ship today entered Japan's territorial waters for the first time in over a decade while tailing two Indian naval ships during trilateral Malabar naval exercise attended by the US, India and Japan.

Japanese P-3C patrol aircraft spotted the Dongdiao-class intelligence vessel sailing in territorial waters to the west of Kuchinoerabu Island at around 3:30 AM (1830 GMT Tuesday), Deputy Chief Cabinet Secretary Hiroshige Seko told reporters.

The ship travelled on a southeasterly bearing and left Japan's territorial waters south of the prefecture's Yakushima Island around 5 AM, Kyodo news agency quoted Seko as saying.

It was for the first time that a Chinese spy ship was detected in Japanese water since a submarine was spotted in 2004. The latest intrusion came less than a week after another Chinese naval vessel sailed near islands at the centre of a Tokyo-Beijing sovereignty dispute in the East China Sea.

"The Chinese military vessel moved in after an Indian ship sailed into Japan's territorial waters as it participated in a Japan-US-India joint exercise," Defence Minister Gen Nakatani told reporters.

A senior Foreign Ministry official lodged a protest with the Chinese Embassy here over its military activities in view of latest intrusion.

"We are concerned about the Chinese military's recent activities," Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida told reporters.

Japanese officials said they are analysing China's possible motives behind the two actions.

"The government will continue to exert every effort in warning and surveillance activities in the waters and airspace surrounding the country," Seko said.

As to the spy vessel's case today, the Defense Ministry said it entered the waters while tracking two Indian naval ships that were participating in ongoing Malabar naval drills.

In Beijing, Chinese officials defended the naval vessel's entry into the waters, saying the passage was in line with the principle of freedom of navigation and international rules.

Under international law, ships of all countries, including military ones, are entitled to the right of "innocent passage" through territorial waters as long as it would not undermine others' security.

"There is no need to provide notification or to get authorisation in advance," Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Lu Kang said in Beijing.

"So if Japan insists on hyping up this issue in the media, we have to question its motives."

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

Scuffle at border as Indian troops counter aggressive Chinese incursions in Arunachal Pradesh

During the normal banner drill, the PLA troops striking an aggressive posture tried to attack the Indian Army personnel physically but were overpowered immediately, official sources said today.

-

member_23370

- BRFite

- Posts: 1103

- Joined: 11 Aug 2016 06:14

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

The chinese are rattled to the core. Before the NSG meeting I expect a few more CVN's to fins their way to SCS. Obama is using Bush's strategy. The only thing missing are the Ohio's.

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

The extent of the US India agreement being elaborate and broad based was a surprise for PRC ChinaBheeshma wrote:The chinese are rattled to the core. Before the NSG meeting I expect a few more CVN's to fins their way to SCS. Obama is using Bush's strategy. The only thing missing are the Ohio's.

There are some hidden aspects of the agreement which only China understands. More later on that.

Before PM Modi arrived in US there was back door diplomacy and lobbying by China Pak lobby in DC

They wanted to find the text of the agreement and also omit anything which would impact them. PRC could manage the removal of south china sea.

But they are still unhappy since India get support for all the things which China was wary about.

There may have been evil eyes on PM Modi visit to DC. PRC has activated its army at the Indian border even before Modi visit. The threat and the blackmail to India is overt to get a direct veto on the US India agreement.

All these postures are to test the relative strengths of PRC on one side against India US standing together.

There has been previous threat before.

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/03/world ... nsion.html

He added, however, that growing cooperation with the United States had forced China to take India more seriously.

Shen Dingli, a professor of international relations at Fudan University in Shanghai, dismissed the idea that the grouping could be revived, and said that India would not join such a network for fear of Chinese retaliation.

“China actually has many ways to hurt India,” he said. “China could send an aircraft carrier to the Gwadar port in Pakistan. China had turned down the Pakistan offer to have military stationed in the country. If India forces China to do that, of course we can put a navy at your doorstep.”

-

member_23370

- BRFite

- Posts: 1103

- Joined: 11 Aug 2016 06:14

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

China has no functional aircraft carrier. Heck the Vikrant with harriers would be enough for that floating junk yard they have.

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

Lost in the palace of Chinese illusions - G.Parthasarathy, Business Line

New Delhi appeared shocked by China’s recent veto of action against the chief of the Jaish-e-Mohammed, Maulana Masood Azhar, when there was widespread support in the UN Sanctions Committee to act against him for his role in the Pathankot attack. The UN declared the Jaish-e-Mohammed a terrorist organisation in 2001.

The former director-general of the ISI, Lt Gen Javed Ashraf Qazi, acknowledged in Pakistan’s parliament in 2004 that the Jaish-e-Mohammed was responsible for the attack on the Indian parliament — an action that took the two countries to the brink of war. This veto was, however, not an isolated action by China, which has long backed Pakistan-sponsored terrorism against India.

Old news

China’s contacts with radical Islamic groups backed by the ISI is nothing new. It was one of the few countries that had contacts with high-level Taliban leaders, including Mullah Omar, during Taliban rule between 1996 and 2000. There was even a Chinese offer to establish a telephone network in Kabul during this period. Moreover, after the Taliban was ousted from power in 2001 and was hosted by the ISI in Quetta, the Chinese maintained clandestine contacts with the Mullah Omar-led Quetta Shura. China recently joined the ISI to sponsor a so-called Afghan-led peace process with the Kabul government.

Beijing appears convinced of the need to have an ISI-friendly government in Kabul. The mandarins in Beijing evidently favour such a dispensation in the belief that the ISI will rein in Taliban support for Uighur Muslim militants in Xinjiang.

While India received overwhelming international sympathy and support during the 26/11 terrorist carnage, the Chinese reaction was one of almost unbridled glee, backing Pakistani protestations of innocence. The state-run China Institute of Contemporary International Relations claimed that the terrorists who carried out the attack came from India. Moreover, even as the terrorist strike was on, a Chinese ‘scholar’ gleefully noted: “The Mumbai attack exposed the internal weakness of India, a power that is otherwise raising its status both in the region and in the world.”

Not to be outdone, the foreign ministry-run China Institute of Strategic Studies warned, “China can firmly support Pakistan in the event of war”, adding, “While Pakistan can benefit from its military co-operation with China while fighting India, the People’s Republic of China may have the option of resorting to a strategic military action in Southern Tibet (Arunachal Pradesh), to liberate the people there”. Rather than condemning the terrorists and their supporters, Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Qin Gang urged India and Pakistan to “maintain calm” and investigate the “cause” of the terror attack jointly. The visiting chairman of Pakistan’s joint chiefs of staff general, Tariq Majid, was received in Beijing like a state dignitary by Chinese leaders, with promises of support on weapons supplies ranging from fighter aircraft to frigates.

Powerful lobbying

China has developed strong lobbies in Indian business. Political parties, journalists and academics act as apologists for its actions even when such actions constitute what can only be described as unrelenting hostility towards India’s national security concerns. Even the ‘ayatollahs’ of nonproliferation in the US who rant and rave against India’s nuclear and missile programmes, suddenly lose their tongue when it comes to condemning Chinese actions. They have documented evidence on how China initially provided nuclear weapons designs to Pakistan for its enriched uranium warheads and also upgraded Pakistan’ uranium enrichment capabilities. More ominously, China provided a range of designs and materials for Pakistan to develop plutonium reactors, heavy water plants and plutonium separation facilities in the Khushab-Fatehjang-Chashma nuclear complex. This has enabled Pakistan to make light plutonium warheads and embark on the production of tactical nuclear weapons.

This development has seriously enhanced the prospect of Pakistan triggering a nuclear conflict by the use of tactical nuclear weapons. Pakistan now no longer speaks of a “credible minimum deterrent” but of possessing a “full spectrum deterrent”. There has been no other instance in the contemporary world of such largescale and unrestrained transfer of nuclear weapons capabilities as what transpired during the past four decades between China and Pakistan. Worse, while China balks at backing India’s entry to the Missile Technology Control Regime {China has not done that because it is itself not a member of MTCR} , virtually every ballistic missile in Pakistan’s inventory today is of Chinese origin. The 750-900-km Shaheen 1 is a variant of the Chinese DF-15 missile. Shaheen 2 and Shaheen 3 with a range of 1,700 km and 2,750 km respectively, are evidently variants of the Chinese DF-21A.

Strategic containment

New Delhi should have no doubt that Beijing’s ties with Pakistan are primarily motivated by a burning desire for the “strategic containment” of India. New Delhi appears to be still looking for a coherent strategy to pay back China in its own coin and raise the strategic costs for Beijing’s unrelenting hostility towards its security interests. India needs more pro-active coordination of its policies with those of key regional powers such as Japan and Vietnam, to meet the challenges China now poses. India, Vietnam and Japan should jointly seek to coordinate these efforts with the US. Washington, unfortunately, has a track record of striking its own deals with China, with scant regard for the interests of its partners. Moreover, while dealing with these maritime and strategic challenges, India has to simultaneously strengthen confidence building measures (CBM) on its land borders with China. These CBMs have been useful, especially after President XI Jin Ping’s visit to India, in maintaining peace along the Sino-Indian border. It is going to take a long time before the border issue is sorted out with China, in accordance with the Guiding Principles agreed to in 2005.

It is astonishing that in all these years there has been no significant or sustained diplomatic effort by successive governments in India to focus attention on these developments. And the less said about our journalists and academics visiting the Middle Kingdom, the better. They are generally busy singing the praises of their hosts than bothering about such issues. While the invitation to Chinese dissidents for a meeting in Dharamsala could have been handled more professionally, China should be made to pay a price for meddling in developments in our north-eastern States.

The writer is a former High Commissioner to Pakistan

-

RKumar

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

No incursion into Arunachal Pradesh; it is our land: China - PTI

As Sino-India border has not yet been demarcated, what is stopping us to perform "normal patrols" few kilometres deep in Tibet. It will give some energy to Tibetans living in Tibet

China today rejected allegation of incursion by its troops in Arunachal Pradesh, saying the Sino-India border has not yet been demarcated and the soldiers of the People's Liberation Army were conducting "normal patrols" on the Chinese side of the Line of Actual Control.

"China and India border has not yet been demarcated," Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman, Lu Kang told media briefing here answering a question of reports of 250 Chinese troops entering Yangste, East Kameng district on June 9.

As Sino-India border has not yet been demarcated, what is stopping us to perform "normal patrols" few kilometres deep in Tibet. It will give some energy to Tibetans living in Tibet

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

For all you know, that may be happening too. It is for China to publicize such 'intrusions', but they may choose not to do so for various reasons. On its own, India would not talk about that because, after all, it is on its territory !RKumar wrote:As Sino-India border has not yet been demarcated, what is stopping us to perform "normal patrols" few kilometres deep in Tibet. It will give some energy to Tibetans living in Tibet

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

Fu Xiaoqiang a “research fellow with the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations” writing in the P.R. China Government Controlled paper Global Times on India’s Nuclear Supplier Group aka NSG membership.

Presuming Fu Xiaoqiang is parroting the Communist line, P.R.China seems happy to accept India’s NSG membership in exchange for India subordinating her foreign policy to toeing P.R.China’s line:

Presuming Fu Xiaoqiang is parroting the Communist line, P.R.China seems happy to accept India’s NSG membership in exchange for India subordinating her foreign policy to toeing P.R.China’s line:

Beijing could support India’s NSG accession path if it plays by rulesAs long as all NSG members reach a consensus over how a non-NPT member could join the NSG, and India promises to comply with stipulations over the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons while sticking to its policy of independence and self-reliance, China could support New Delhi's path toward the club.

-

RKumar

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

I disagree with your above sentence. We might be visiting our land controlled by Sino but doing "normal patrols" few kilometres deep in Tibet via AP route .... na na. I am highly doubtful with our current military preparedness. Because of our Dharmic values, we don't try to snatch others valuables/land. But this is not we can expect to get back in return.SSridhar wrote:For all you know, that may be happening too.

I completely agree with your comments.SSridhar wrote:It is for China to publicize such 'intrusions', but they may choose not to do so for various reasons. On its own, India would not talk about that because, after all, it is on its territory !

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

IOW, They want surrity about Vietnam and Other Naams in China's neighborhood.arun wrote:Fu Xiaoqiang a “research fellow with the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations” writing in the P.R. China Government Controlled paper Global Times on India’s Nuclear Supplier Group aka NSG membership. Presuming Fu Xiaoqiang is parroting the Communist line, P.R.China seems happy to accept India’s NSG membership in exchange for India subordinating her foreign policy to toeing P.R.China’s line:Beijing could support India’s NSG accession path if it plays by rulesAs long as all NSG members reach a consensus over how a non-NPT member could join the NSG, and India promises to comply with stipulations over the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons while sticking to its policy of independence and self-reliance, China could support New Delhi's path toward the club.

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

Except you did try to snatch those lands, in '62, and just like now, the people of India were unaware of it and were caught off guard when the Chinese responded in kind.RKumar wrote:I disagree with your above sentence. We might be visiting our land controlled by Sino but doing "normal patrols" few kilometres deep in Tibet via AP route .... na na. I am highly doubtful with our current military preparedness. Because of our Dharmic values, we don't try to snatch others valuables/land. But this is not we can expect to get back in return.SSridhar wrote:For all you know, that may be happening too.

I completely agree with your comments.SSridhar wrote:It is for China to publicize such 'intrusions', but they may choose not to do so for various reasons. On its own, India would not talk about that because, after all, it is on its territory !

-

RKumar

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

1) Which land are you talking about? Historically, India had no border with China till 1958-59 till China forcefully occupied a peaceful nation Tibet. And due to world's as well as India's stupidity no one protested against China's action.DavidD wrote:Except you did try to snatch those lands, in '62, and just like now, the people of India were unaware of it and were caught off guard when the Chinese responded in kind.

2) We never tried to snatch any land. But world should support the Tibet to get freedom from China.

3) We have to take back our land which is forcefully occupied by Pak, China.

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

DavidD, can you substantiate your claim?DavidD wrote:Except you did try to snatch those lands, in '62, and just like now, the people of India were unaware of it and were caught off guard when the Chinese responded in kind.

-

sanjaykumar

- BRF Oldie

- Posts: 6110

- Joined: 16 Oct 2005 05:51

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

Wha? These Chinese are demonstrably robotised, denied information by their own great firewall of China, sponsored to parrot the party's position. Read something other than Global Times, or do you get sent to Turkestan (without a pistol) for that?

-

BharadwajV

- BRFite

- Posts: 116

- Joined: 11 Aug 2016 06:14

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

Looks like someone got their history books from the

-

sanjaykumar

- BRF Oldie

- Posts: 6110

- Joined: 16 Oct 2005 05:51

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

More likely they get their information from the back of a box of tea.

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

X-post from India Foreign policy thread.

India to export missile systems to 'certain' friendly nations: Manohar Parrikar - PTI

India to export missile systems to 'certain' friendly nations: Manohar Parrikar - PTI

Government has decided in principle to allow export of missile systems to 'certain' countries who have friendly relationship with India, Defence Minister Manohar Parrikar said on Friday.

"The government had taken a very conscious decision about 4-5 months ago that 10 per cent of the missile capacity will be permitted to be exported if producers manage to get export orders subject to parameters set by the Union government and external affairs ministry," he told reporters here.

Policy of export was always existing earlier, but the problem was lack of spare capacity after meeting requirement of the country's armed forces, he said, adding that the production capacity for various missile systems like ' Akash ' had been been improved now.

"In-principle decision has been taken to allow exports to certain countries who are in friendly relationship with us... if they manage to export, then we would enhance the capacity by 10 per cent so that the forces are not deprived," he said.

Parrikar, here [Bengaluru] for the inaugural flight of indigenous basic trainer aircraft Hindustan Turbo Trainer-40 (HTT-40), was responding to a question on export policy.

On possible export of BrahMos missiles to Vietnam, which he had visited earlier this month, he said the southeast Asian country had expressed interest and a group would be set up to discuss about their requirement.

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

China snatches lands. China grabs what belongs to others. Communist China does not know geography. It does not know history. Worst! it takes the world to be same as the robotized Chinese it lords over. It could have been a friendly neighbor to India but the company China keeps tells its own story, no?DavidD wrote: ...

Except you did try to snatch those lands, in '62, and just like now, the people of India were unaware of it and were caught off guard when the Chinese responded in kind.

China has 02 friends only - One is NoKo and for someone to call NoKo friendly is a statement about that "someone".

Here is another friend of NoKo

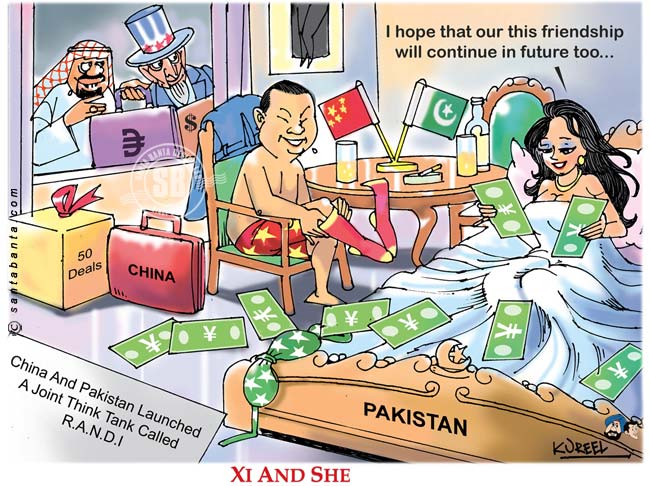

Then there is the other friend of China - Tallel, sweetel, deepel, highel, stlongel - PAKISTAN! It really is a friendship which defines the Chinese mindset of identifying with what it thinks is good - exploit, grab, snatch. It starts as in the left cartoon and will end as in right cartoon. China snatches land just like Hitler snatched land for greater Lebensraum. It tried with India in 1962 and met its match. China can only exploit Pakistan and NoKo like states.

Here David for yours eyes to 2C

Re: Managing Chinese Threat (09-08-2014)

Silk Road to (economic) heaven - Talmiz Ahmed, Former Indian Ambassador to KSA

This was originally published in The Wire, IndiaNew Delhi is concerned about the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor project (CPEC), part of the new ‘Silk Road’, but it need not despair as India is an important part of the existing multi-polar Asia architecture.

The signing of the Chabahar port development agreement and the tripartite pact on a trade and transit corridor linking India, Afghanistan and Iran during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s recent visit to Iran has re-opened the discussion in New Delhi about what position it should adopt on the Chinese-sponsored logistics project, One Belt, One Road (OBOR).

Some background to this would be useful.

In September 2013, during a visit to Kazakhstan, China’s president, Xi Jinping, announced a Chinese initiative — the setting up of connectivities across the landmass of Eurasia and the waters of the Indian Ocean that would collectively be known as the OBOR. He anchored this vision in the old ‘Silk Road,’ which in his view had originated with the encounters of imperial envoy Zhang Qian (200-113 BC) with Central Asian civilisations over two millennia earlier.

Since then, the OBOR has become the most important element in Chinese economic and political diplomacy, as its leaders, officials and academics attempt to fine-tune their thinking and get more supporters — governments, officials and the corporate – on board for this dramatic enterprise that has the potential to fundamentally transform the world’s communications, and its economic and political landscape.

The old Silk Road

The old Silk Road had a vibrant life of over three millennia, linking Asia with Europe and emerging as the principal conduit for the movement of global trade, merchants, preachers, professionals and intellectuals. It was marked by hundreds of market towns: Xian, Chengdu, Kunming and Kashgar in China; Khotan, Samarkhand and Bokhara in Central Asia; Taxila, Persepolis, Bagram, Kandahar and Merv in India and Iran, and Tyre and Antioch in the Mediterranean.

The sea routes linked the ports of Northeast, Southeast and South Asia with the Arabian Peninsula, and then through the West Asian caravan routes, and the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea routes, went westwards to the Mesopotamian and Egyptian empires and culminated in Greece and Rome.

The impact of these connections was both material and civilisational: China and India, as the US academic Craig Lockard has noted, “were the great pre-modern centres of world manufacturing, producing iron, steel, silk, cotton and ceramics for world markets”. Beyond commerce, over the centuries these land and sea routes also facilitated the movement of religious and civilisational concepts – beliefs and practices of Zoroastrianism, Nestorian Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam interacted with each other through these time-honoured links and shaped the civilisations of Mesopotamia, Persia, India and China and imbued western culture with these ancient Asian reflections and belief-systems.

The new Silk Road connections

The old Silk Road ceased to have much regional importance from the 15th century onwards on account of political and military disruptions across Eurasia, and the discovery of sea routes from the West to Asian markets. These sea routes in time led to western military and political control of the high seas, including the Indian Ocean, as also of almost all of the Asian lands, which now came under British, French or Dutch control. Thus, the main economic links of Asian countries were now with European states, with the centuries-old intra-Asian commercial and civilisational connectivities now consigned to the margins of their day-to-day experience.

This scenario of western political and economic domination of Asia began to change after the end of the Cold War. First, from the 1990s, Asian countries such as China and India began to achieve high growth rates and emerge as major economic powers. Second, these high growth rates in Asia generated a substantial increase in demand for energy resources, particularly for oil and gas. These were available in plenty in West Asia, leading to a shift in energy supplies from west to east. This surge in energy demand also meant that the West Asian producers came to enjoy extraordinary inflows of financial resources for domestic infrastructure and welfare development, and to invest in world markets.

The third factor that served to change the global power equation was the emergence of the Central Asian republics as sovereign states and their ability to play an independent role in the global energy and geopolitical scenario. These developments together brought an end to Western hegemony over Asia and for the first time in two hundred years gave Asian countries the opportunity to re-establish age-old connectivity with each other.

These new connections were in the areas of energy, trade and investment, and were shaped at a time of great economic resurgence across Asia. Thus, a decade before Xi’s announcement of the OBOR, a thriving “Silk Road” connectivity had already come to link the Asian countries and constitute their most important economic relationship. The OBOR thus proposes giving a physical shape to the existing rich and substantial ties.

The OBOR routings

Reflecting at the land and sea routes of the old Silk Road linkages, the OBOR has land and sea dimensions that converge at certain points, which together constitute an extraordinary seamless connectivity that embraces all of Eurasia and the Indian Ocean littoral. The Eurasian land connection, known as the “New Silk Road Economic Belt” or simply the “Belt,” is made up of railways, highways, oil and gas pipelines, and major energy projects.

Beginning at Xian, the legendary starting point of the old Silk Road, the OBOR will have two routings: one, across China to Kazakhstan and then Moscow, and the other through Mongolia and southern Russia to Moscow. Both routes will merge and then go on to European cities — Budapest, Hamburg and Rotterdam. The southern route will branch into one that will cross Iran and Turkey, and end at Budapest. It will have another branch from the Pakistani port of Gwadar to the Chinese city of Kashgar in the western province of Xinjiang.

The sea route, known as the “Maritime Silk Road” or simply the “Road,” made up of ports and coastal development, begins from China’s eastern ports and goes on to Southeast Asia, South Asia, East Africa and then on to West Asia and the Mediterranean, embracing Greece and Venice and ending at Rotterdam. Both routes, again recalling the old Silk Road, will have a series of loops and branches, with the two main routes also meeting at important junctions, such as Gwadar, Istanbul, Rotterdam and Hamburg.

According to Korean scholar Jae Ho Chung, when completed, the OBOR will include 60 countries, with two-thirds of the world’s population, 55 percent of the global GDP and 75per cent of global energy reserves. It will consist of 900 infrastructure projects, valued at about 1.3 trillion US dollars. Much of the funding is expected to come from Chinese banks, financial institutions and special funds. The Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post has described the OBOR as “the most significant and far-reaching project the nation has ever put forward”.

Promoting the OBOR

The OBOR initiative has captured world attention for the sheer range and audacity of the concept, the extraordinary ambition that lies at its base and the significant resources — technological, human, financial and political — that will need to be garnered globally to realise the vision. Since the first announcement, Chinese officials and commentators have debated the project, fleshed out several loose ends and sought to bring as many countries as possible on board as partners.

These have included a series of engagements with policymakers in countries on the OBOR routes. The OBOR was of course initiated in Central Asia and China has obtained the support of these republics with promises of massive investment for regional development. Xi has said China will support the construction of 4000 kilometres of railways and 10,000 kilometres of highways in Central Asia, with nearly 16 billion US dollars of Chinese funding.

The next most important interaction China has had on the OBOR is with Russia. China has benefited from Russian estrangement from the West following the events in Ukraine – and the consequent abandoning of the Russian “Greater Europe” project that would have linked Vladivostok with Lisbon – and developed energy, financial, technological and defence ties with Moscow. This has led to Russian acceptance of China’s presence in Central Asia and the merging of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s Eurasian Economic Union project with the OBOR.

In October 2013, Xi reached out to the ASEAN countries and sought to bring them within the fold of the maritime route by invoking 14th century Chinese mariner Zheng He (1371-1433/35), who explored South and Southeast Asia, and proposing the building of a close-knit China-ASEAN community. Following this, Xi met a Gulf Cooperation Council delegation in January 2014 and attempted to make West Asia a partner in the OBOR as well.

The drivers of the OBOR

In promoting the OBOR, China is being driven by domestic and foreign considerations. The urge to achieve development in all of China’s 31 provinces is a major factor and all provinces have already affirmed their active participation in different aspects of the enterprise. The western province of Qinghai has indicated that it will build a rail, highway and aviation network to link the provinces and countries along the OBOR; Guangdong province along the coast will execute some major infrastructure projects, such as a power plant in Vietnam and an oil refinery in Myanmar.

The realisation of the OBOR will of course see the western province of Xinjiang playing a major role – its cities of Urumqi, Kashgar and Khorgos will be at the centre of many of the proposed routes. OBOR-related projects will also provide an outlet for China to use its overcapacity in steel, cement and construction materials, as also its surplus financial reserves.

Chinese scholar Tingyi Wang of Tsinghua University has explained that while the OBOR is prompted by China’s interests in energy, security and promotion of economic ties, it is actually driven by the vision of a “greater Eurasian idea” that calls for “strengthening economic and cultural integration” across this whole swathe of territory and building “a new type of international relations underpinned by win-win cooperation”. Wang summarises the Chinese strategy as “to guarantee its interests in this region and at the same time cooperate with the other powers”.

Former Indian Foreign Secretary Shyam Saran sees the OBOR not just as economic initiative but one that has clear political and security implications; it is for Saran “a carving out by China of a continental-marine geo-strategic realm”.

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

The one aspect of the OBOR that has caused the greatest concern in India, both in regard to its land and maritime implications, is the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Finalised in April 2015 on the basis of 51 agreements, the CPEC consists of a series of highway, railway and energy projects, emanating from the newly developed port of Gwadar on the Arabian Sea, all of which taken together will be valued at 46 billion US dollars. These projects will generate 700,000 jobs in Pakistan and, when completed, add 2-2.5 per cent to the country’s GDP. The CPEC has been described as a “flagship project” for the OBOR.

Gwadar will be developed as a deep-water port capable of handling 300-400 million tonnes of cargo per year. A new 1100-kilometres motorway from Karachi to Lahore will be completed, while the Karakoram Highway from Rawalpindi to the Chinese border will be re-constructed. Railway lines across the country will be thoroughly upgraded and expanded, with the road and railway network reaching Kashgar in Xinjiang. Oil and gas pipelines will be constructed, including a gas pipeline from Gwadar to Nawabshah, carrying gas from Iran. Most of the money will be spent on energy projects – about 10,400 MW of electricity will be developed between 2018-20, besides renewable energy, coal and liquefied natural gas projects. An 800-kilometres optic fibre link to boost telecommunications in the Gilgit-Baltistan region is already under construction. These projects will promote national economic development through industrial parks and special economic zones.

Washington-based Council on Foreign Relations described CPEC as “part development scheme, part strategic gambit” in a recent report. By investing heavily in Pakistan’s development, particularly in its backward regions, China is clearly addressing its own concerns relating to security problems whose roots are in Pakistan. The most important of these is the threat from the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), made up of Chinese-dissident Uighur militant groups that have taken sanctuary in the Pakistan-Afghanistan border areas and are said to be linked to al-Qaeda and the Taliban. The ETIM aims its violence at targets in China and also at Chinese interests in Pakistan.