A Mach 14 Waverider glide vehicle, which takes its name from its ability to generate high lift and ride on its own shock waves. This shape is representative of the type of systems the United States is developing today

A Mach 14 Waverider glide vehicle, which takes its name from its ability to generate high lift and ride on its own shock waves. This shape is representative of the type of systems the United States is developing today.

CreditCreditDan Winters for The New York Times

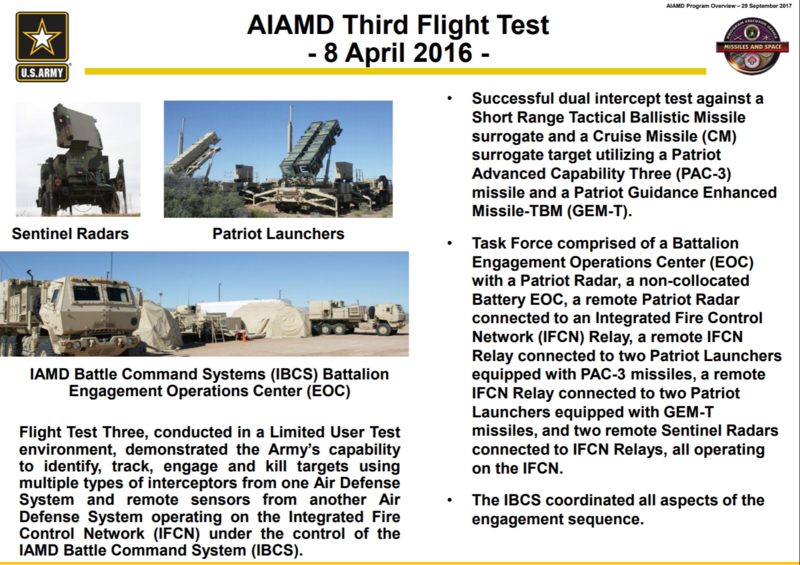

On March 6, 2018, the grand ballroom at the Sphinx Club in Washington was packed with aerospace-industry executives waiting to hear from Michael D. Griffin. Weeks earlier, Secretary of Defense James Mattis named the 69-year-old Maryland native the Pentagon’s under secretary for research and engineering, a job that comes with an annual budget of more than $17 billion. The dark-suited attendees at the McAleese/Credit Suisse Defense Programs Conference were eager to learn what type of work he would favor.

The audience was already familiar with Griffin, an unabashed defender of American military and political supremacy who has bragged about being labeled an “unreconstructed cold warrior.” With five master’s degrees and a doctorate in aerospace engineering, he was the chief technology officer for President Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative (popularly known as Star Wars), which was supposed to shield the United States against a potential Russian attack by ballistic missiles looping over the North Pole. Over the course of his career that followed, he wrote a book on space vehicle design, ran a technology incubator funded by the C.I.A., directed NASA for four years and was employed as a senior executive at a handful of aerospace firms.

Griffin was known as a scientific optimist who regularly called for “disruptive innovation” and who prized speed above all. He had repeatedly complained about the Pentagon’s sluggish bureaucracy, which he saw as mired in legacy thinking. “This is a country that produced an atom bomb under the stress of wartime in three years from the day we decided to do it,” he told a congressional panel last year. “This is a country that can do anything we need to do that physics allows. We just need to get on with it.”

In recent decades, Griffin’s predecessors had prioritized broad research into topics such as human-computer interaction, space communication and undersea warfare. But Griffin signaled an important shift, one that would have major financial consequences for the executives in attendance. “I’m sorry for everybody out there who champions some other high priority, some technical thing; it’s not that I disagree with those,” he told the room. “But there has to be a first, and hypersonics is my first.”

Griffin was referring to a revolutionary new type of weapon, one that would have the unprecedented ability to maneuver and then to strike almost any target in the world within a matter of minutes. Capable of traveling at more than 15 times the speed of sound, hypersonic missiles arrive at their targets in a blinding, destructive flash, before any sonic booms or other meaningful warning. So far, there are no surefire defenses. Fast, effective, precise and unstoppable — these are rare but highly desired characteristics on the modern battlefield. And the missiles are being developed not only by the United States but also by China, Russia and other countries.

Griffin is now the chief evangelist in Washington for hypersonics, and so far he has run into few political or financial roadblocks. Lawmakers have supported a significant expansion of federal spending to accelerate the delivery of what they call a “game-changing technology,” a buzz phrase often repeated in discussions on hypersonics. America needs to act quickly, says James Inhofe, the Republican senator from Oklahoma who is chairman of the Armed Services Committee, or else the nation might fall behind Russia and China. Democratic leaders in the House and Senate are largely in agreement, though recently they’ve pressed the Pentagon for more information. (The Senate Armed Services Committee ranking member Jack Reed, a Democrat from Rhode Island, and House Chairman Adam Smith, the Democratic representative for Washington’s ninth district, told me it might make sense to question the weapons’ global impact or talk with Russia about the risks they create, but the priority in Washington right now is to get our versions built.)

Interior of the high-velocity wind tunnel in White Oak, Md., where scientists are testing hypersonic missile prototypes

Interior of the high-velocity wind tunnel in White Oak, Md., where scientists are testing hypersonic missile prototypes.

CreditDan Winters for The New York Times

In 2018, Congress expressed its consensus in a law requiring that an American hypersonic weapon be operational by October 2022. This year, the Trump administration’s proposed defense budget included $2.6 billion for hypersonics, and national security industry experts project that the annual budget will reach $5 billion by the middle of the next decade. The immediate aim is to create two deployable systems within three years. Key funding is likely to be approved this summer.

The enthusiasm has spread to military contractors, especially after the Pentagon awarded the largest one, Lockheed Martin, more than $1.4 billion in 2018 to build missile prototypes that can be launched by Air Force fighter jets and B-52 bombers. These programs were just the beginning of what the acting defense secretary, Patrick M. Shanahan, described in December as the Trump administration’s goal of “industrializing” hypersonic missile production. Several months later, he and Griffin created a new Space Development Agency of some 225 people, tasked with putting a network of sensors in low-earth orbit that would track incoming hypersonic missiles and direct American hypersonic attacks. This isn’t the network’s only purpose, but it will have “a war-fighting capability, should it come to that,” Griffin said in March.

Development of hypersonics is moving so quickly, however, that it threatens to outpace any real discussion about the potential perils of such weapons, including how they may disrupt efforts to avoid accidental conflict, especially during crises. There are currently no international agreements on how or when hypersonic missiles can be used, nor are there any plans between any countries to start those discussions. Instead, the rush to possess weapons of incredible speed and maneuverability has pushed the United States into a new arms race with Russia and China — one that could, some experts worry, upend existing norms of deterrence and renew Cold War-era tensions.

Although hypersonic missiles can in theory carry nuclear warheads, those being developed by the United States will only be equipped with small conventional explosives. With a length between just five and 10 feet, weighing about 500 pounds and encased in materials like ceramic and carbon fiber composites or nickel-chromium superalloys, the missiles function like nearly invisible power drills that smash holes in their targets, to catastrophic effect. After their launch — whether from the ground, from airplanes or from submarines — they are pulled by gravity as they descend from a powered ascent, or propelled by highly advanced engines. The missiles’ kinetic energy at the time of impact, at speeds of at least 1,150 miles per hour, makes them powerful enough to penetrate any building material or armored plating with the force of three to four tons of TNT.

They could be aimed, in theory, at Russian nuclear-armed ballistic missiles being carried on trucks or rails. Or the Chinese could use their own versions of these missiles to target American bombers and other aircraft at bases in Japan or Guam. Or the missiles could attack vital land- or sea-based radars anywhere, or military headquarters in Asian ports or near European cities. The weapons could even suddenly pierce the steel decks of one of America’s 11 multibillion-dollar aircraft carriers, instantly stopping flight operations, a vulnerability that might eventually render the floating behemoths obsolete. Hypersonic missiles are also ideal for waging a decapitation strike — assassinating a country’s top military or political officials. “Instant leader-killers,” a former Obama administration White House official, who asked not to be named, said in an interview.

Within the next decade, these new weapons could undertake a task long imagined for nuclear arms: a first strike against another nation’s government or arsenals, interrupting key chains of communication and disabling some of its retaliatory forces, all without the radioactive fallout and special condemnation that might accompany the detonation of nuclear warheads. That’s why a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine report said in 2016 that hypersonics aren’t “simply evolutionary threats” to the United States but could in the hands of enemies “challenge this nation’s tenets of global vigilance, reach and power.”

The arrival of such fast weaponry will dangerously compress the time during which military officials and their political leaders — in any country — can figure out the nature of an attack and make reasoned decisions about the wisdom and scope of defensive steps or retaliation. And the threat that hypersonics pose to retaliatory weapons creates what scholars call “use it or lose it” pressures on countries to strike first during a crisis. Experts say that the missiles could upend the grim psychology of Mutual Assured Destruction, the bedrock military doctrine of the nuclear age that argued globe-altering wars would be deterred if the potential combatants always felt certain of their opponents’ devastating response.

And yet decision makers seem to be ignoring these risks. Unlike with previous leaps in military technology — such as the creation of chemical and biological weapons and ballistic missiles with multiple nuclear warheads — that ignited international debate and eventually were controlled through superpower treaty negotiations, officials in Washington, Moscow and Beijing haven’t seriously considered any sort of accord limiting the development or deployment of hypersonic technology. In the United States, the State Department’s arms-control bureau has an office devoted to emerging security challenges, but hypersonic missiles aren’t one of its core concerns. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s deputies say they primarily support making the military’s arsenal more robust, an unusual stance for a department tasked with finding diplomatic solutions to global problems.

This position worries arms-control experts like Thomas M. Countryman, a career diplomat for 35 years and former assistant secretary of state in the Obama administration. “This is not the first case of a new technology proceeding through research, development and deployment far faster than the policy apparatus can keep up,” says Countryman, who is now chairman of the Arms Control Association. He cites examples of similarly “destabilizing technologies” in the 1960s and 1970s, when billions of dollars in frenzied spending on nuclear and chemical arms was unaccompanied by discussion of how the resulting dangers could be minimized. Countryman wants to see limitations placed on the number of hypersonic missiles that a country can build or on the type of warheads that they can carry. He and others worry that failing to regulate these weapons at the international level could have irreversible consequences.

“It is possible,” the United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs said in a February report, that “in response [to] the deployment of hypersonic weapons,” nations fearing the destruction of their retaliatory-strike capability might either decide to use nuclear weapons under a wider set of conditions or simply place “nuclear forces on higher alert levels” as a matter of routine. The report lamented that these “ramifications remain largely unexamined and almost wholly undiscussed.”

So why haven’t the potential risks of this revolution attracted more attention? One reason is that for years the big powers have cared mostly about numerical measures of power — who has more warheads, bombers and missiles — and negotiations have focused heavily on those metrics. Only occasionally has their conversation widened to include the issue of strategic stability, a topic that encompasses whether specific weaponry poses risks of inadvertent war.

An aerospace engineer for the military for more than three decades, Daniel Marren runs one of the world’s fastest wind tunnels — and thanks to hypersonics research, his lab is in high demand. But finding it takes some time: When I arrived at the Air Force’s White Oak testing facility, just north of Silver Spring, Md., the private security guards only vaguely gestured toward some World War II-era military research buildings down the road, at the edge of the Food and Drug Administration’s main campus. The low-slung structure that houses Marren’s tunnel looks as if it could pass for an aged elementary school, except that it has a seven-story silver sphere sticking out of its east side, like a World’s Fair exhibit in the spot where an auditorium should be. The tunnel itself, some 40 feet in length and five feet in diameter, looks like a water main; it narrows at one end before emptying into the silver sphere. A column of costly high-tech sensors is grafted onto the piping where a thick window has been cut into its midsection.

Marren seemed both thrilled and harried by the rising tempo at his laboratory in recent months. A jovial 55-year-old who speaks carefully but excitedly about his work, he showed me a red brick structure on the property with some broken windows. It was built, he said, to house the first of nine wind tunnels that have operated at the test site, one that was painstakingly recovered in 1948 from Peenemünde, the coastal German village where Wernher von Braun worked on the V-2 rocket used to kill thousands of Londoners in World War II. American military researchers had a hard time figuring out how to reassemble and operate it, so they recruited some German scientists stateside.

As we entered the control room of the building that houses the active tunnel, Marren mentioned casually that the roof was specially designed to blow off easily if anything goes explosively awry. Any debris would head skyward, and the engineers, analysts and visiting Air Force generals monitoring the wind tests could survive behind the control room’s reinforced-concrete walls.

Inside the main room, Marren — dressed in a technologist’s polo shirt — explained that during the tests, the tunnel is first rolled into place on a trolley over steel rails in the floor. Then an enormous electric burner is ignited beneath it, heating the air inside to more than 3,000 degrees, hot enough to melt steel. The air is then punched by pressures 1,000 times greater than normal at one end of the tunnel and sucked at the other end by a vacuum deliberately created in the enormous sphere.

That sends the air roaring down the tunnel at up to 18 times the speed of sound — fast enough to traverse more than 30 football fields in the time it takes to blink. Smack in the middle of the tunnel during a test, attached to a pole capable of changing its angle in fractions of a second, is a scale model of the hypersonics prototype. That is, instead of testing the missiles by flying them through the air outdoors, the tunnel effectively makes the air fly past them at the same incredible pace.

For the tests, the models are coated with a paint that absorbs ultraviolet laser light as it warms, marking the spots on their ceramic skin where frictional heat may threaten the structure of the missile; engineers will then need to tweak the designs either to resist that heat or shunt it elsewhere. The aim, Marren explains, is to see what will happen when the missiles plow through the earth’s dense atmosphere on their way to their targets.

It’s challenging work, replicating the stresses these missiles would endure while whizzing by at 30 times the speed of a civilian airliner, miles above the clouds. Their sleek, synthetic skin expands and deforms and kicks off a plasma like the ionized gas formed by superheated stars, as they smash the air and try to shed all that intense heat. The tests are fleeting, lasting 15 seconds at most, which require the sensors to record their data in thousandths of a nanosecond. That’s the best any such test facility can do, according to Marren, and it partly accounts for the difficulty that defense researchers have had in producing hypersonics, even after about $2 billion-worth of federal investment before this year.

Nonetheless, Marren, who has worked at the tunnel since 1984, is optimistic that researchers will be able to deliver a working missile soon. He and his team are operating at full capacity, with hundreds of test runs scheduled this year to measure the ability of various prototype missiles to withstand the punishing friction and heat of such rapid flight. “We have been prepared for this moment for some time, and it’s great to lean forward,” Marren says. The faster that weapons systems can operate, he adds, the better.

Last year, the nation was confronted with a brief reminder of how Cold War-era nuclear panic played out, after a state employee in Hawaii mistakenly sent out an emergency alert declaring that a “ballistic missile threat” was “inbound.” The message didn’t specify what kind of missile — and, in fact, the United States Army Space and Missile Defense Command at two sites in Alaska and California may have some capability to shoot down a few incoming ballistic missiles — but panicked Hawaii residents didn’t feel protected. They reacted by careening cars into one another on highways, pushing their children into storm drains for protection and phoning their loved ones to say goodbye — until a second message, 38 minutes later, acknowledged it was an error.

Hypersonics pose a different threat from ballistic missiles, according to those who have studied and worked on them, because they could be maneuvered in ways that confound existing methods of defense and detection. Not to mention, unlike most ballistic missiles, they would arrive in under 15 minutes — less time than anyone in Hawaii or elsewhere would need to meaningfully react.

How fast is that, really? An object moving through the air produces an audible shock wave — a sonic boom — when it reaches about 760 miles per hour. This speed of sound is also called Mach 1, after the Austrian physicist Ernst Mach. When a projectile flies faster than Mach’s number, it travels at supersonic speed — a speed faster than sound. Mach 2 is twice the speed of sound; Mach 3 is three times the speed of sound, and so on. When a projectile reaches a speed faster than Mach 5, it’s said to travel at hypersonic speed.

One of the two main hypersonic prototypes now under development in the United States is meant to fly at speeds between Mach 15 and Mach 20, or more than 11,400 miles per hour. This means that when fired by the U.S. submarines or bombers stationed at Guam, they could in theory hit China’s important inland missile bases, like Delingha, in less than 15 minutes. President Vladimir Putin has likewise claimed that one of Russia’s new hypersonic missiles will travel at Mach 10, while the other will travel at Mach 20. If true, that would mean a Russian aircraft or ship firing one of them near Bermuda could strike the Pentagon, some 800 miles away, in five minutes. China, meanwhile, has flight-tested its own hypersonic missiles at speeds fast enough to reach Guam from the Chinese coastline within minutes.

One concept now being pursued by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency uses a conventional missile launched from air platforms to loft a smaller, hypersonic glider on its journey, even before the missile reaches its apex. The glider then flies unpowered toward its target. The deadly projectile might ricochet downward, nose tilted up, on layers of atmosphere — the mesosphere, then the stratosphere and troposphere — like an oblate stone on water, in smaller and shallower skips, or it might be directed to pass smoothly through these layers. In either instance, the friction of the lower atmosphere would finally slow it enough to allow a steering system to maneuver it precisely toward its target. The weapon, known as Tactical Boost Glide, is scheduled to be dropped from military planes during testing next year.

Under an alternative approach, a hypersonic missile would fly mostly horizontally under the power of a “scramjet,” a highly advanced, fanless engine that uses shock waves created by its speed to compress incoming air in a short funnel and ignite it while passing by (in roughly one two-thousandths of a second, according to some accounts). With its skin heated by friction to as much as 5,400 degrees, its engine walls would be protected from burning up by routing the fuel through them, an idea pioneered by the German designers of the V-2 rocket.

The unusual trajectories of these missiles would allow them to approach their targets at roughly 12 to 50 miles above the earth’s surface. That’s below the altitude at which ballistic missile interceptors — such as the costly American Aegis ship-based system and the Thaad ground-based system — are now designed to typically operate, yet above the altitude that simpler air defense missiles, like the Patriot system, can reach.

Officials will have trouble even knowing where a strike would land. Although the missiles’ launch would probably be picked up by infrared-sensing satellites in its first few moments of flight, Griffin says they would be roughly 10 to 20 times harder to detect than incoming ballistic missiles as they near their targets. They would zoom along in the defensive void, maneuvering unpredictably, and then, in just a few final seconds of blindingly fast, mile-per-second flight, dive and strike a target such as an aircraft carrier from an altitude of 100,000 feet.

During their flight, the perimeter of their potential landing zone could be about as big as Rhode Island. Officials might sound a general alarm, but they’d be clueless about exactly where the missiles were headed. “We don’t have any defense that could deny the employment of such a weapon against us,” Gen. John E. Hyten, commander of United States Strategic Command, told the Senate Armed Services Committee in March 2018. The Pentagon is just now studying what a hypersonic attack might look like and imagining how a defensive system might be created; it has no architecture for it, and no firm sense of the costs.

Developing these new weapons hasn’t been easy. A 2012 test was terminated when the skin peeled off a hypersonic prototype, and another self-destructed when it lost control. A third hypersonic test vehicle was deliberately destroyed when its boosting missile failed in 2014. Officials at Darpa acknowledge they are still struggling with the composite ceramics they need to protect the missiles’ electronics from intense heating; the Pentagon decided last July to ladle an extra $34.5 million into this effort this year.

The task of conducting realistic flight tests also poses a challenge. The military’s principal land-based site for open-air prototype flights — a 3,200-acre site stretching across multiple counties in New Mexico — isn’t big enough to accommodate hypersonic weapons. So fresh testing corridors are being negotiated in Utah that will require a new regional political agreement about the noise of trailing sonic booms. Scientists still aren’t sure how to accumulate all the data they need, given the speed of the flights. The open-air flight tests can cost up to $100 million.

The most recent open-air hypersonic-weapon test was completed by the Army and the Navy in October 2017, using a 36,000-pound missile to launch a glider from a rocky beach on the western shores of Kauai, Hawaii, toward Kwajalein Atoll, 2,300 miles to the southwest. The 9 p.m. flight created a trailing sonic boom over the Pacific, which topped out at an estimated 175 decibels, well above the threshold of causing physical pain. The effort cost $160 million, or 6 percent of the total hypersonics budget proposed for 2020.

In March 2018, Vladimir Putin, in the first of several speeches designed to rekindle American anxieties about a foreign missile threat, boasted that Russia had two operational hypersonic weapons: the Kinzhal, a fast, air-launched missile capable of striking targets up to 1,200 miles away; and the Avangard, designed to be attached to a new Sarmat intercontinental ballistic missile before maneuvering toward its targets. Russian media have claimed that nuclear warheads for the weapons are already being produced and that the Sarmat missile itself has been flight-tested roughly 3,000 miles across Siberia. (Russia has also said it is working on a third hypersonic missile system, designed to be launched from submarines.) American experts aren’t buying all of Putin’s claims. “Their test record is more like ours,” said an engineer working on the American program. “It’s had a small number of flight-test successes.” But Pentagon officials are convinced that Moscow’s weapons will soon be a real threat.

The exterior of the wind tunnel. At 40 feet long and five feet in diameter, the tunnel replicates the forces missiles would endure at hypersonic speeds

The exterior of the wind tunnel. At 40 feet long and five feet in diameter, the tunnel replicates the forces missiles would endure at hypersonic speeds.

CreditDan Winters for The New York Times

Analysts say the Chinese are even further along than the Russians, partly because Beijing has sought to create hypersonic missiles with shorter ranges that don’t have to endure high temperatures as long. Many of their tests have involved a glide vehicle. Last August, a contractor for the Chinese space program claimed that it successfully flight-tested a gliding hypersonic missile for slightly more than six minutes. It supposedly reached a speed exceeding Mach 5 before landing in its target zone. Other Chinese hypersonic missile tests have reached speeds almost twice as fast.

And it’s not just Russia, China and the United States that are interested in fast-flying military power drills. France and India have active hypersonics development programs, and each is working in partnership with Russia, according to a 2017 report by the Rand Corp., a nonpartisan research organization. Australia, Japan and the European Union have either civilian or military hypersonics research underway, the report said, partly because they are still tantalized by the prospect of making super-speedy airplanes large enough to carry passengers across the globe in mere hours. But Japan’s immediate effort is aimed at making a weapon that will be ready for testing by 2025.

This is not the first time the United States or others have ignored risks while rushing toward a new, apparently magical solution to a military threat or shortcoming. During the Cold War, America and Russia competed fiercely to threaten each other’s vital assets with bombers that took hours to cross oceans and with ballistic missiles that could reach their targets in 30 minutes. Ultimately, each side accumulated more than 31,000 warheads (even though the detonations of just 100 weapons would have sparked a severe global famine and stripped away significant protections against ultraviolet radiation). Eventually the fever broke, partly because of the Soviet Union’s dissolution, and the two nations reduced their arsenals through negotiations to about 6,500 nuclear warheads apiece.

Since then, cycles of intense arms racing have restarted whenever one side has felt acutely disadvantaged or spied a potential exit from what the political scientist Robert Jervis once described as the “overwhelming nature” of nuclear destruction, a circumstance that we’ve been involuntarily and resentfully hostage to for the past 70 years.

Trump officials in particular have resisted policies that support Mutual Assured Destruction, the idea that shared risk can lead to stability and peace. John Bolton, the national security adviser, was a key architect in 2002 of America’s withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty with Russia, which limited both nations’ ability to try to block ballistic missiles. He asserted that freeing the United States of those restrictions would enhance American security, and if the rest of the world was static, his prediction might have come true. But Russia started its hypersonics program to ensure it could get around any American ballistic missile defenses. “Nobody wanted to listen to us” about the strategic dangers of abandoning the treaty, Putin said last year with an aggressive flourish as he displayed videos and animations of his nation’s hypersonic missiles. “So listen now.”

But not much listening is going on in either country. In January, the Trump administration released an updated missile-defense strategy that explicitly calls for limiting mutual vulnerability by defeating enemy “offensive missiles prior to launch.” The administration also continues to eschew any new limits on its own missiles, arguing that past agreements lulled America into a dangerous post-Cold War “holiday,” as a senior State Department official described it.

The current administration’s lack of interest in regulating hypersonics isn’t that different from its predecessor’s. Around 2010, President Obama privately “made it clear that he wanted better options to hold North Korean missiles” at risk, a former senior adviser said, and some military officials said hypersonic weapons might be suitable for this. About that same time, the most recent nuclear arms reduction agreement with Russia deliberately excluded any constraints on hypersonic weapons. Then, three years ago, a New York-based group called the Lawyers Committee on Nuclear Policy, acting in conjunction with other nonprofits committed to disarmament, called on the president to head off a hypersonic competition and its anticipated drain on future federal budgets by exploring a joint moratorium with China and Russia on testing. The idea was never taken up.

The Obama administration’s inaction helped open the door to the 21st-century hypersonic contest America finds itself in today. “We always do these things in isolation, without thinking about what it means for the big powers — for Russia and China — who are batshit paranoid” about a potential quick, pre-emptive American attack, the adviser said, expressing regret about how the issue was handled during Obama’s tenure.

While it might not be too late to change course, history shows that stopping an arms race is much harder than igniting one. And Washington at the moment is still principally focused on “putting a weapon on a target,” as a longtime congressional staff member put it, rather than the reaction this capability inspires in an adversary. Griffin even projects an eventual American victory in this race: In April 2018, he said the best answer to the Chinese and Russian hypersonic programs is “to hold their assets at risk with systems similar to but better than what they have fielded.” Invoking the mantra of military scientists throughout time, Griffin added that the country must “see their hand and raise them one.” The world will soon find out what happens now that the military superpowers have decided to go all in.