http://carnegieendowment.org/syriaincrisis/?fa=61941

This September, the long-besieged Abu al-Dhuhour Airbase was captured by al-Qaeda’s Nusra Front after a two-year siege. The Saudi jihadi preacher Abdullah al-Moheisini, who is now an influential figure in rebel-ruled Idlib City, then held a videotaped speech calling on Sunni families to learn from what was about to happen and stop sending their sons to Assad’s army. The Nusra Front later released pictures of some fifty prisoners lined up on the airstrip and executed, blood drying on sun-drenched concrete.

These massacres are not simply wanton cruelty. They are designed to induce fear, limit recruitment, and sap the morale of isolated SAA garrisons. Assad’s enemies want to teach his supporters that once trapped, their only choice is to either buy their survival by surrendering territory or to die in the most nightmarish fashion. But in Kweiris, Assad undid the lesson of Abu al-Dhuhour, showing his troops that with Russia on the battlefield, they can fight and survive.

THE ROAD TO RAQQA

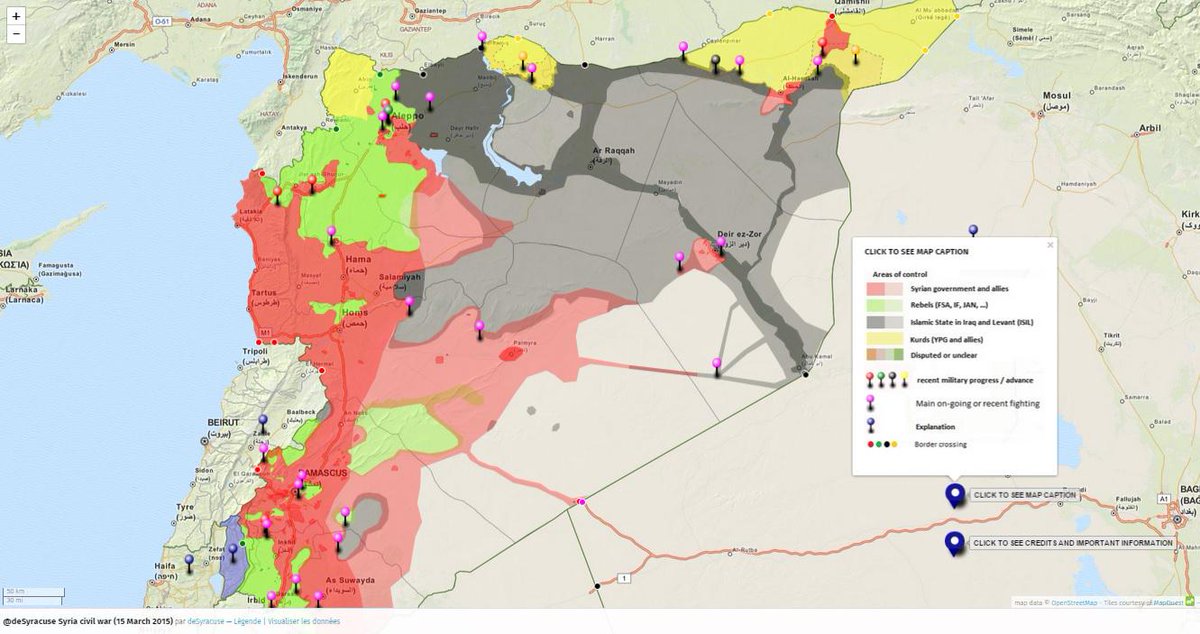

Last, and perhaps most importantly, there is a way in which the Kweiris battle matters to the larger struggle against the Islamic State—because by capturing the airbase, Assad threatens communications between the Islamic State’s so called capital in Raqqa and its largest military front in Aleppo.

The Islamic State’s administration in the eastern Aleppo area is centered in the two rural centers of al-Bab and Manbij. Although there is no longer an open border crossing at Jarabulous, on the western shore of the Euphrates, the area still serves as the Islamic State’s sole remaining point of access to Turkey, through which foreign fighters and smuggled goods arrive to the Islamic State. The region also includes Dabiq, a tiny town near the frontline that plays an outsized religious and political significance due to its role in the armageddon of Islamic eschatology. Last but not least, eastern Aleppo holds forth a promise of enormous material gain if the jihadis should manage to break through rebel defenses in the Marea-Azaz area north of Aleppo, or cut the above-mentioned supply line that runs through Sfeira down to Assad-held territory in Hama.

From eastern Syria and the Iraqi border, the east-west Highway 4 runs to Raqqa and then on toward Aleppo. Once in Raqqa, you could formerly take one of two routes to get to the frontlines around Aleppo.

The northern route feeds into the M4 Highway from Hasakah and crosses the Euphrates near Manbij, but it was cut by U.S.-backed Kurdish forces bursting out of Kobane this spring. In May, the Islamic State blew up the last remaining bridge over the Euphrates in the Jarabulous area, in an attempt to seal the frontline and use the river as natural protection from the Kurds. From that point on, the northern route is no longer an option.

The southern route, on which you continue west from Raqqa along Highway 4, was always the main connection to Aleppo. It never crosses the Euphrates and therefore cannot be cut by bridge bombings. Unfortunately for the Islamic State, the M4 then hits Kweiris Airbase. Although we must presume that this particular stretch of the road has been out of commission for a while due to the heavy fighting, this final stretch of the road has now been taken by the Syrian Arab Army.

To be clear, this does not mean that the Islamic State can no longer ferry troops between Raqqa and Aleppo. It can. Highway 4 has three northern offshoots toward Manbij and al-Bab and either one of them will do just fine to get troops into this region. But if Assad’s troops decide to press on from Kweiris, they are now within realistic striking distance of the closest one, which springs from the intersection at Deir Hafer to provide direct access to the Islamic State’s regional administrative center in al-Bab. The more pressure that is put on the road network in this area, the more it will impede and endanger Islamic State logistics.

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN?

Now, let’s not get ahead of ourselves. The battles in this area have flowed back and forth. According to a Syrian military source speaking to Reuters, the army is still working to secure the area. In other words, the Islamic State could still retake Kweiris or Assad might voluntarily decide to pull out once the base’s defenders have been evacuated.

But if neither of those things happen, and the Assad-Putin alliance continues to press forward east of Aleppo, it will create a very interesting situation. Politically speaking, Kweiris will then have earned Assad and Russia a small but far from insignificant victory in the struggle against the Islamic State. Militarily speaking, it might complicate the jihadis’ operations in the eastern Aleppo countryside, which could in turn help U.S.-backed anti-Assad rebels north of Aleppo, around Marea, to turn the tables on the jihadi group.

The interlinked nature of the battles against the Islamic State in the Aleppo region is not something that either Assad or the rebels will be eager to recognize, since their ultimate goal is to eradicate the other. Neither will the United States want to publicly credit Russia with any advances against the jihadis. But in the long run, should such an unspoken interdependence really develop, it could create some really interesting American-Russian and regime-rebel synergies in northern Syria.

And that is, of course, exactly what Russia is looking for.