Re: Indian Urban Development and Public Policy Discussion

Posted: 07 Feb 2015 12:36

Bus Rapid Transit: A Tale of Three Cities

Delhi vs Pune vs Ahmedabad compared

Delhi vs Pune vs Ahmedabad compared

Consortium of Indian Defence Websites

https://forums.bharat-rakshak.com/

Interesting debates on the matter:In fact, a new initiative to upzone Mumbai, India is probably the most important urban-policy development in the world today. It should fairly dramatically increase living standards in one of the biggest cities on the planet and possibly do a great deal to drive economic growth forward throughout India.

Zoning news from the third world isn't the kind of thing most people in the west are going to pay attention to. But as India is both the world's largest democracy and has the world's largest concentration of poor people, its success or failure in generating rising living standards is a huge deal. And getting urban planning right is a huge piece of that.

One important measurement in the urban-planning world is what Americans call Floor Area Ratio (FAR) and what Indians call Floor Space Index (FSI). FAR/FSI measures the ratio of built-out floor space to land area. In a suburban area full of one-floor buildings, large lawns, and generous parking lots you would expect FAR to be well below 1. In midtown Manhattan, which is full of very tall buildings, FARs get as high as 15.

Mumbai currently has a regulatory ceiling of 1.33 FAR for the central city and 1 for more outlying areas. In the United States, a 1.33 FAR would probably be a neighborhood full of three story row-houses. In other words, a kind of low-density residential urbanism.

But making this the maximum allowed building density in a low-income city of 12 million people has created a very different situation: Mumbai's infamous hyper-crowded slums, as seen in Katherine Boo's Beyond the Beautiful Forevers. Alain Berteaud points out that contrary to what you might guess, "a lot of slum dwellers are gainfully employed and are not poor in terms of their relative income. Rather, they are the victims of a number of misguided land use policies and of a lack of government investments in infrastructure."

By Indian standards, in other words, Mumbai has good opportunities for jobs and incomes. So people have flooded into the city. But the city has not allowed for remotely adequate levels of new construction. Consequently, by 2009 the average Mumbai resident had just 48 square feet of residential space at his disposal compared to about 365 square feet in Shanghai.

The proposed change

Greater Mumbai's governing authority is proposing a sweeping change to the permitted FARs in the area. Under the plan, Mumbai would be divided into five zones with an FAR of 8 allowed in the very densest areas and FARs in the 5-6 range in places well-served by mass transit. Fifty-eight percent of the city's land area would remain below 3.5, but even that could mean significant increases in the amount of building allowed in many areas.

New construction should have four major economic impacts:

Existing Mumbai residents should be able to obtain more living space for themselves, allowing for higher real living standards even in the absence of wage increases.

It should become more feasible for more Indians to relocate to Mumbai and its relatively robust economy, increasing wages and productivity nationwide.

The new construction itself will generate jobs.

With more space at their disposal, Mumbai residents can accumulate more consumer goods, increasing demand for higher-end products.

The proposed change doesn't come directly from the central Indian government, but does reflect priorities of the still-relatively-new prime minister Narendra Modi. As leader of the Indian state of Gujarat he increased density in several cities and often linked new building permits to infrastructure funding.

Even a city as large as Mumbai contains only a relatively small fraction of India's vast population. But it is in many respects the country's most economically dynamic metropolis, so its decisions have big national implications. And if the change goes through and is seen to pay off, it could inspire further reforms across the country that give urban Indians the opportunity for better homes and better lives.

Collectively, Port Trust land sprawls across 752.24 hectares or roughly one-eighth the size of the island city, Mumbai’s southern core, once the limits of the old city of Bombay. Most of the docklands unfold along a 14-km waterfront, laced with road and rail.

The plan–integrated with Mumbai’s upcoming 2014-2034 Development Plan–proposes the eastern seaboard be revitalised on the values of what it calls “intelligent urbanism”, the catchwords being open, green and connected.

‘Open’ for new public uses, such as recreation, culture, tourism and community amenities. ‘Connected’ through multiple transportation modes: walkways, cycle tracks, metro, ferries and bus rapid transit. ‘Green’, to ensure environmentally sustainable land use.

The plan calls for 30% of docklands to be set aside for open spaces, another 30% for transport and infrastructure and 40% for mixed-use development for businesses, the fishing industry, office and retail markets and a finance centre.

According to a study conducted by the Ministry of Urban Development in 2008, only 20% of trips are undertaken by personal modes of transport in Indian cities with populations of over 80 lakh. The remaining 80% are undertaken by public transport, walking, cycling, and intermediate modes of public transportation (IPT) such as auto-rickshaws, taxis and cycle-rickshaws. The mode share of personal vehicles in three of the four ‘metros’ is less than 20%, Chennai being the outlier in that group with a 30% personal vehicle mode share. { I had always thought Chennai's vehicle usage was lower than this, considering the number of people who take buses and trains in the city. But a large number of suburban commuters drive to the local railway station to take a train to work. I don't know how that is counted. } Bangalore and Hyderabad, both Tier 1 cities, also have personal vehicle mode shares of under 30%. If we were to now superimpose investments on urban road projects on the same chart, we’d find that an overwhelmingly large proportion of investments have been cornered by projects aimed at helping personal modes of transport (the 30% crowd). For a country where car users are a minority, it is hugely ironical that pedestrians, cyclists and public transport users, the majority, often end up getting the short end of the stick in getting their mobility needs addressed probably because they aren’t vocal enough.

Irony keeps coming under the car in India like it did in Delhi when car users filed a lawsuit against the Delhi BRT. { And the Delhi AAP govt wants to shut this system down, instead of making some improvements and attract more ridership. Another irony the author didn't call out.} Barely had irony recovered from this accident that Kolkata decided to ban cycles (11% mode share) on its roads to ‘ease congestion’, a euphemism for giving undue advantage to car users (8% mode share).

If we were to look around us, we’d be hard pressed to find footpaths and cycle tracks. It is because over the years, our cities have used discretionary powers to benefit their preferred group, i.e., automobile users solely because the latter are more vocal about their needs.

{ I can attest to this. In the '90s, when the DMK govt and Stalin as Mayor of Chennai built a bunch of flyovers, a lot of footpaths were done away with in order to widen the roads. Chennai wasn't very pedestrian friendly to begin with, but it went from bad to worse in the '90s. Only now is the trend sort of reversing, though there are miles to go before one can walk, to paraphrase Tennyson. The pic below is still quite common in the city. }

Even roads that have footpaths prove their existence merely as a technicality such as the one on the right. If you’re a pedestrian though, a discontinuous footpath, even if it is paved, is as uncomfortable and frustrating as a discontinuous road is for vehicle users.

If you were a commuter in this area shown in the photo and were asked to make a decision on your choice of travel mode, what would you choose, being a pedestrian or being in your vehicle? It is a no brainer isn’t it? If we were to repeat this exercise for every commuter in the same area, we’d find that a large majority of commuters would be more inclined towards using private vehicles and hence would contribute towards increasing the load on our already overburdened roads.

When faced with such situations, our cities have either taken out or reduced the widths of footpaths to widen roads as part of their vehicle-oriented projects. True to their nature, vehicle oriented projects have done what they invariably do, nudge people to move away from City centers, a phenomenon known as urban sprawl. Remember the overzealous builder trying to sell his new project 20 km from the main city by talking about that famed 80m DP road that’s about to come up in the area? Rings a bell?

This has been happening across all our big cities, people are spreading out and it is evident from the same MoUD study.

The average trip lengths in our cities has been increasing, an indication that we’re driving more and longer than before. Between 1994 and 2007, the average trip length in Tier I cities increased by 30% and is expected to increase by approximately 43% between 2011 and 2031.

Longer trip lengths have an inverse relationship with walking and cycling, and a direct relation with congestion. They create a vicious cycle of more investments in vehicle-centric projects and reduction in walk and cycle trips. This is primarily why we find our cities clogged today despite having much wider roads than what we had a decade ago. More widening is akin to loosening our belts to cure obesity.

But there is growing hope, based on recent trends, that our cities are making the right moves. Several municipalities and metropolitan development authorities are increasingly taking a more progressive approach while allocating valuable tax rupees on urban infrastructure projects. Some of the credit for this change must go to India’s National Urban Transport Policy (NUTP) which unequivocally makes it clear that transportation projects should take into account the needs of all modes and all users, not just personal vehicles as has been the practice so far.

The Corporation of Chennai (CoC) has taken a lead in this regard and it should be lauded for adopting a policy aimed at creating pedestrian and cyclist friendly infrastructure for its citizens. The policy document states that the CoC aims to make Chennai:

“a city with a general sense of well-being through the development of quality and dignified environment where people are encouraged to walk and cycle; equitable allocation of public space and infrastructure; and access to opportunities and mobility for all residents”. (emphasis mine).

What CoC aims to do is ensure that its roads follow the policy popularly known as ‘Complete Streets’. As the name suggests, Complete Streets are those that are designed to serve all user groups, including people with disabilities, pedestrians, cyclists, public transport, and vehicular traffic. The overall objective of the ‘Complete Streets’ policy, which is gradually becoming a global movement of sorts, is to provide equitable mobility for all and eliminate traditional discrimination against certain user groups.

In its policy document, the CoC has set itself some targets against which it will measure itself going forward. These targets include

[*] Increasing the mode share of pedestrians and cyclists from 30% in 2007 to 40%;

[*] Reducing the number of pedestrian and cyclist fatalities to 0 per year, popularly known as the ‘Vision Zero’ and adopted by several public agencies around the world;

[*] Ensuring that 80% of streets have footpaths;

[*] Ensuring that 80% of streets with widths of 30m of more have unobstructed and continuous cycle tracks;

[*] Increasing the mode share of public transport from 30% in 2007 to 60%; and

[*] Reducing vehicle kilometres travelled by personal modes of transport, i.e., reduce trip lengths and mode share of personal modes of transport.[/list]

To achieve these targets, the CoC has outlined a set of proven strategies in its policy document. These include, among other things, following the ‘Complete Streets’ design policy for all its road projects, and favouring at-grade pedestrian facilities instead of overhead crossings and pedestrian subways. It also proposes to implement BRT corridors with dedicated bus lanes, create more ‘eyes on the street’ by setting up dedicated vending spaces along pedestrian routes, and creation of pedestrian zones throughout the city. { I am not sure if it is related to this project, but the past 2 years have seen a serious upgrade of interior streets in the city, with defined width, reflectors, street signs etc. It gave a good impression of uniformity for the city, considering the metro is administered by a combination of municipal corporation, municipalities, town panchayats, and so on, and the smaller local bodies adopted the corporation's template to upgrade their roads as well. So it was good spinoff by setting an example. }

The best part of this initiative is the creation of a ‘Chennai Street Design Manual’. By creating this document, the CoC has perhaps become the first municipal body in India to have its own set of design standards and guidelines, something that has been woefully missing in Indian cities.

The result of this policy can now be seen on ground with the completion of several revitalisation projects such as, but not limited to, Halls Road, Police Commissioner’s Office Road, Pantheon Road, and MG Road. It is indeed heartening to see an Indian municipal corporation ‘walking’ the talk, hope others follow suit. { Has anyone seen the ground implementation at these roads? There was an article on The Hindu last week saying some footpaths are broken soon after construction. Quality and implementation is always the problem! }

To prevent open defecation, the civic body in the city today introduced a novel concept of rewarding people to use the public toilets.

The civic body will identify people who defecate in open and will encourage them to use corporation-run toilets by rewarding them with an incentive of one rupee, Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation in-charge Health officer Bhavik Joshi said.

"Standing Committee of AMC decided to reward those people, who will use civic body public toilets instead of open defecation. They will be given an incentive of Re one for using the lavatory facilities," he said.

According to Joshi, AMC has already identified around 1,200 such people in various parts of the city and this list will be revised at regular intervals.

There are 120 places in the city, where activities of open defecation were registered, he said, adding that AMC will provide lavatory facilities in all those areas.

The project will get started by next week, the officer said.

srin wrote:That's what you term as a $hit-load of money

Sorry. I frequent the "finished" section on Cunningham road and the worksmanship is plainly Kakkoose.for Theo sir, finally a footpath in blr with std workmanship, materials, sloping and a buried duct for all cables.

this is the new pedestrian friendly St Marks rd bluru - the revolution has began! death to the feudals! shiver tokyo shiver!

Yes. This TenderSure thing is on at Cunningham Road, Vittal Mallya Road, in front of St Josephs' College/ St Marks Road from what I see, maybe other places as well.Singha wrote:cunningham road? isn't that far to the north behind the police commissioners office? st marks road is only between residency road cash pharmacy to koshy's/hard rock cafe in MG road

Yes it is. I travel there on a regular basis. The whole plan was poorly planned. The footpaths are just too wide. The road in front of Vitttal Mallya hospital used to see traffic jams everyday. Now things are just worse. And if I recollect correctly, BWSSB dug up a portion of St. Marks road saying they 'forgot to connect the old and new pipes', after the completion of the TenderSure work.vina wrote:Yes. This TenderSure thing is on at Cunningham Road, Vittal Mallya Road, in front of St Josephs' College/ St Marks Road from what I see, maybe other places as well.Singha wrote:cunningham road? isn't that far to the north behind the police commissioners office? st marks road is only between residency road cash pharmacy to koshy's/hard rock cafe in MG road

IF this Cunnigham road work is any indication, it is Kakkoose.

Vast majority of travel in India takes place by walk. If anything the foot paths need to be even wider and cars must be eliminated from these streets. At these population densities you cannot have a personal vehicle based city.hsrada wrote:The footpaths are just too wide.

1) Wide foot paths are good? Not always. When they are placed on a road where there are people only two times a day (when the nearby St. Joseph's school starts and gets over), when the wide foot paths cause perpetual traffic jams - they are unnecessary.Theo_Fidel wrote: Vast majority of travel in India takes place by walk. If anything the foot paths need to be even wider and cars must be eliminated from these streets. At these population densities you cannot have a personal vehicle based city.

-----------------------------------------

Personally I’m on the fence about Hawkers. I think as we get richer this problem will naturally disappear.

I don’t think the foot paths are causing the traffic jam. So what happens without foot paths when the school is open? People are dodging thru traffic and regularly getting run over. There is more vehicle traffic than the road can handle and this business of commuting through the heart of our cities and squeezing more and more traffic thru is not sustainable. Eliminating the foot traffic today may get you a little more vehicle through put today at the cost of even worse gridlock later. Real hell is coming.hsrada wrote:1) Wide foot paths are good? Not always. When they are placed on a road where there are people only two times a day (when the nearby St. Joseph's school starts and gets over), when the wide foot paths cause perpetual traffic jams - they are unnecessary.

Saar, the bolded part is a good enough reason to have wide footpaths. I echo Theo saar - what will the kids do if the footpaths are narrow? Walk on the road?hsrada wrote:[1) Wide foot paths are good? Not always. When they are placed on a road where there are people only two times a day (when the nearby St. Joseph's school starts and gets over), when the wide foot paths cause perpetual traffic jams - they are unnecessary.

I don't think this is proven at all. So far all we have is anecdotal info about how it 'looks' too wide and may not be fully occupied all the time. Can some one post a picture of this sidewalk with some measurements so we can be a bit more informed. We should not revisit design on the basis of opinion. Someone has spent a lot of time designing based on metrics, they should be paid to remeasure and modify based on data. Thanx.Suraj wrote:t doesn't mean those changes - in this case the footpath widening - is at fault.

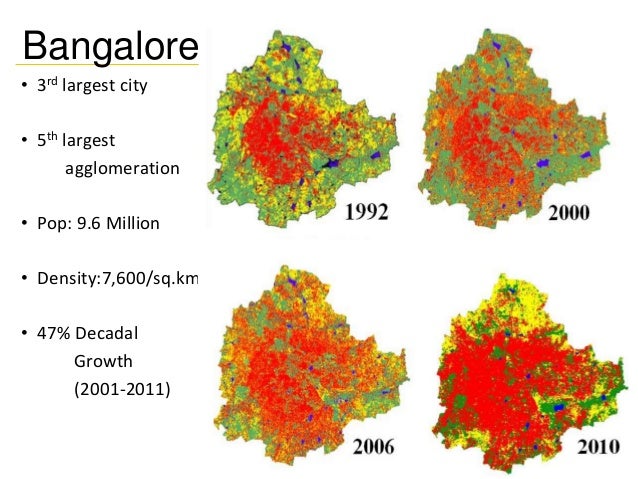

It's going to happen if we dont get our act together. Problem is most state gov could care less.SaiK wrote:we should never grow like this:

china: https://pbs.twimg.com/media/BtzP9o0IYAA-BgF.jpg:large

Traffic Jams in India is largely due to poor driving habits of Indian Drivers, just as most of the accidents. They are a nuisance in terms of driving behavior and civic sense and a threat to life of other road users. Most dangerous of species on Road in India.Picklu wrote: However, the traffic jam there is very very true. Again check the traffic update from google maps if you do not believe.