https://theupheaval.substack.com/p/the- ... onvergence

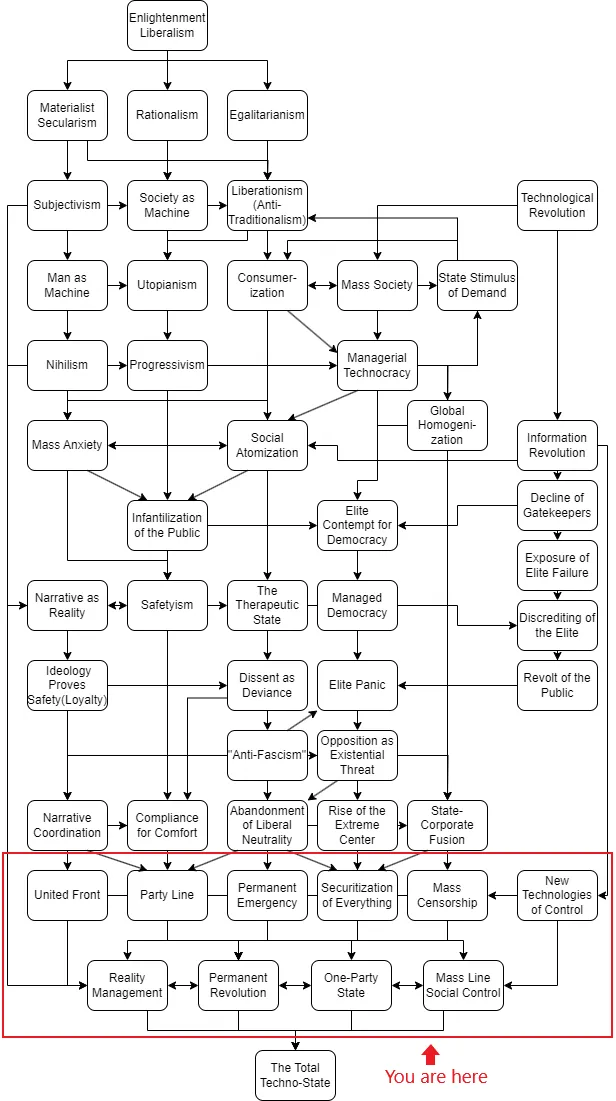

This is the simple and easy narrative of our present moment. In some ways it is accurate: a geopolitical competition really is in the process of boiling over into open confrontation. But it’s also fundamentally shallow and misleading: when it comes to the most fundamental political questions, China and the United States are not diverging but converging to become more alike.

This elite obsession with control is accelerated by a belief in “scientific management,” or the ability to understand, organize, and run all the complex systems of society like a machine, through scientific principles and technologies. The expert knowledge of how to do so is considered the unique and proprietary possession of the elite vanguard.

Ideologically, this elite is deeply materialist, and openly hostile to organized religion, which inhibits and resists state control. They view human beings themselves as machines to be programmed, and, believing the common man to be an unpredictable creature too stupid, irrational, and violent to rule himself, they endeavor to steadily condition and replace him with a better model through engineering, whether social or biological.

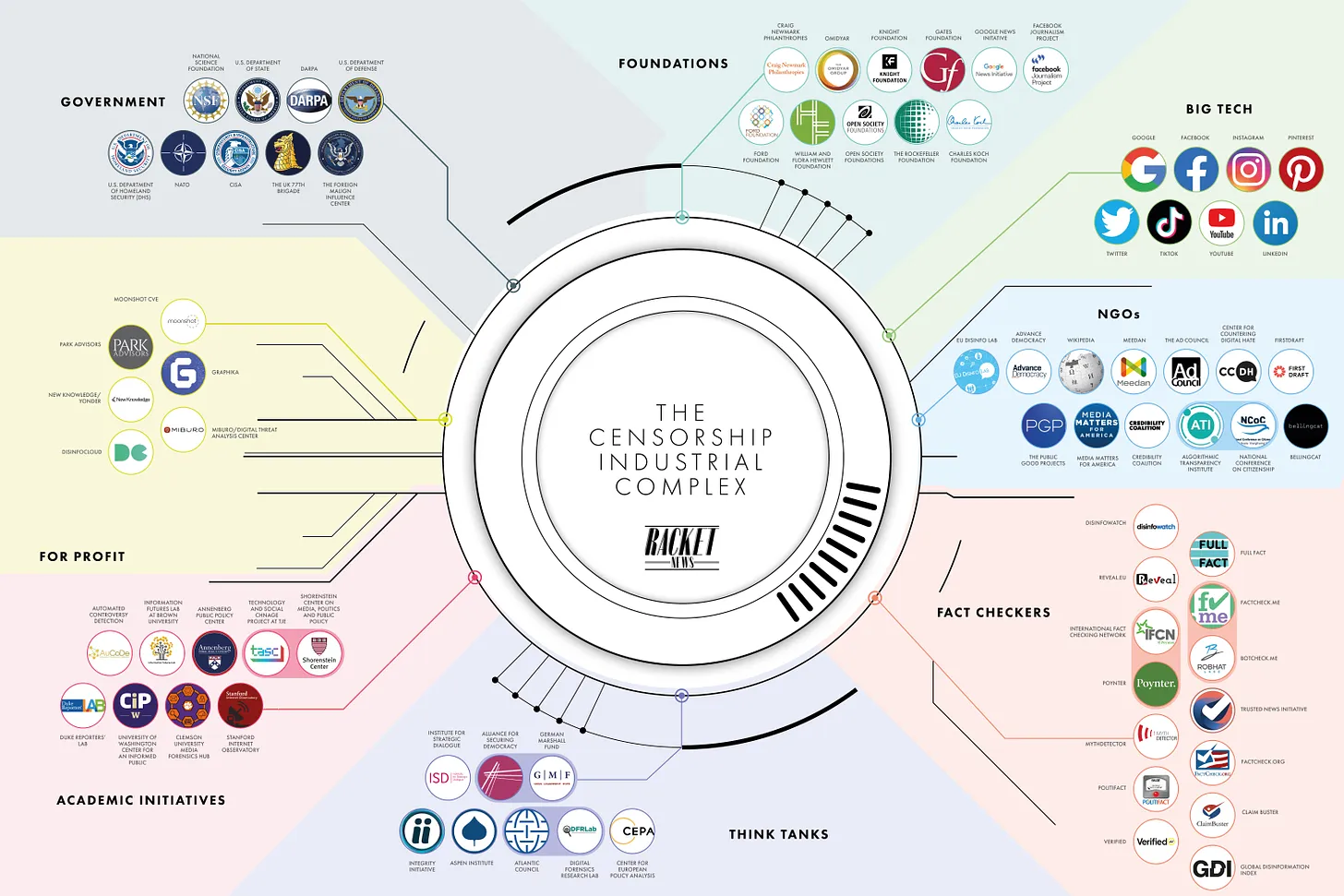

Complex systems of surveillance, propaganda, and coercion are implemented to help firmly nudge (or shove) the common man into line. Communities and cultural traditions that resist this project are dismantled. Harmfully contrary ideas are systematically censored, lest they lead to dangerous exposure. Governing power has been steadily elevated, centralized, and distributed to a technocratic bureaucracy unconstrained by any accountability to the public.

The relentless political messaging and ideological narrative has come to suffuse every sphere of life, and dissent is policed. Culture is largely stagnant. Uprooted, corralled, and hounded, the people are atomized, and social trust is very low. Reality itself often feels obscured and uncertain. Demoralized, some gratefully accept any security offered by the state as a blessing. At the same time, many citizens automatically assume everything the regime says is a lie. Officialdom in general is a Kafkaesque tragi-comedy of the absurd, something only to be stoically endured by normal people. Yet year by year the pressure to conform only continues to be ratcheted higher…

And yet, I’m going to argue that commonalities are indeed growing, and that this is no illusion, coincidence, or conspiracy, but the product of the same deep systemic forces and underlying ideological roots. To claim that we’re the same as China, or even just that we’re turning into China (as I’ve admittedly implied with the title) would really just be political clickbait.

The reality is more complicated, but no less unsettling: both China and the West, in their own ways and at their own pace, but for the same reasons, are converging from different directions on the same point – the same not-yet-fully-realized system of totalizing techno-administrative governance. Though they remain different, theirs is no longer a difference of kind, only of degree. China is just already a bit further down the path towards the same future.

But how should we describe this form of government that has already begun to wrap its tentacles around the world today, including here in the United States? Many of us recognize by now that whatever it is we now live under, it sure isn’t “liberal democracy.” So what is it? To begin answering that, and to really explain the China Convergence, we’re going to need to start with a crash course on the rise and nature of the technocratic managerial regime in the West.

Part I: The Managerial Regime

Rapidly accelerating in the 20th century, the managerial revolution soon began to instigate another transformation of society in the West: it gave birth to a new managerial elite. A new social class had arisen out of the growing scale and complexity of mass organizations as those organizations began to find that, in order to function, they had to rely on large numbers of people who possessed the necessary highly technical and specialized cognitive skills and knowledge, including new techniques of organizational planning and management at scale. Such people became the professional managerial class, which quickly expanded to meet the growing demand for their services.

This did not mean, however, that the expansion of the new managerial order faced no resistance at all from the old order that it strangled. That previous order, which has been referred to by scholars of the managerial revolution as the bourgeois order, was represented not so much by the grande bourgeoisie (wealthy landed aristocrats and early capitalist industrialists) but by the petite bourgeoisie, or what could be described as the independent middle class.[2] The entrepreneurial small business owner, the multi-generational family shop owners, the small-scale farmer or landlord; the community religious or private educator; even the relatively well-to-do local doctor: these and others like them formed the backbone of a large social and economic class that found itself existentially at odds with the interests of the managerial revolution.

The animosity of this class struggle was accentuated by the particularly antagonistic ideology that coalesced as a unifying force for the managerial elite. While this managerial ideology, in its various flavors, presents itself in the lofty language of moral values, philosophical principles, and social goods, it just so happens to rationalize and justify the continual expansion of managerial control into all areas of state, economy, and culture, while elevating the managerial class to a position of not only utilitarian but moral superiority over the rest of society – and in particular over the middle and working classes. This helps serve as a rationale for the managerial elite’s legitimacy to rule, as well as an invaluable means to differentiate, unify, and coordinate the various branches of that elite.

But, in contrast to what was originally predicted by Marxists, these bourgeoisie came to be mortally threatened not from below by the laboring, landless proletariat, but from above, by the new order of the managerial elite and their expanding legions of paper-pushing professional revolutionaries. The clash between these classes, as the managerial order steadily encroached on, dismantled, and subsumed more and more of the middle class bourgeois order and its traditional culture, and the increasingly desperate backlash this process generated from its remnants, would come to define much of the political drama of the West. That drama continues in various forms to this day.

The animosity of this class struggle was accentuated by the particularly antagonistic ideology that coalesced as a unifying force for the managerial elite. While this managerial ideology, in its various flavors, presents itself in the lofty language of moral values, philosophical principles, and social goods, it just so happens to rationalize and justify the continual expansion of managerial control into all areas of state, economy, and culture, while elevating the managerial class to a position of not only utilitarian but moral superiority over the rest of society – and in particular over the middle and working classes. This helps serve as a rationale for the managerial elite’s legitimacy to rule, as well as an invaluable means to differentiate, unify, and coordinate the various branches of that elite.

Managerial ideology, a relatively straightforward descendant of the Enlightenment liberal-modernist project, is a formula that consists of several core beliefs, or what could be called core managerial values. At least in the West, these can be distilled into:

1. Technocratic Scientism: The belief that everything, including society and human nature, can and should be fully understood and controlled through scientific and technical means. In this view everything consists of systems, which operate, as in a machine, on the basis of scientific laws that can be rationally derived through reason. Humans and their behavior are the product of the systems in which they are embedded.

2. Utopianism: The belief that a perfect society is possible – in this case through the perfect application of perfect scientific and technical knowledge. The machine can ultimately be tuned to run flawlessly. At that point all will be completely provided for and therefore completely equal, and man himself will be entirely rational, fully free, and perfectly productive.

This state of perfection is the telos, or pre-destined end point, of human development (through science, physical and social). This creates the idea of progress, or of moving closer to this final end. Consequently history has a teleology: it bends towards utopia. This also means the future is necessarily always better than the past, as it is closer to utopia. History now takes on moral valence; to “go backwards” is immoral. Indeed even actively conserving the status quo is immoral; governance is only moral in so far as it affects change, thus moving us ever forwards, towards utopia.

3. Meliorism: The belief that all the flaws and conflicts of human society, and of human beings themselves, are problems that can and should be directly ameliorated by sufficient managerial technique. Poverty, war, disease, criminality, ignorance, suffering, unhappiness, death… none are examples of the human condition that will always be with us, but are all problems to be solved.

It is the role of the managerial elite to identify and solve such problems by applying their expert knowledge to improve human institutions and relationships, as well as the natural world. In the end there are no tradeoffs, only solutions.

4. Liberationism: The belief that individuals and society are held back from progress by the rules, restraints, relational bonds, historical communities, inherited traditions, and limiting institutions of the past, all of which are the chains of false authority from which we must be liberated so as to move forwards.

Old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits must all be dismantled in order to ameliorate human problems, as old systems and ways of life are necessarily ignorant, flawed, and oppressive. Newer – and therefore superior – scientific knowledge can re-design, from the ground up, new systems and ways of life that will function more efficiently and morally.

5. Hedonistic Materialism: The belief that complete human happiness and well-being fundamentally consists of and is achievable through the fulfillment of a sufficient number of material needs and psychological desires. The presence of any unfulfilled desire or discomfort indicates the systemic inefficiency of an un-provided good that can and should be met in order to move the human being closer to a perfected state.

Scientific management can and should therefore to the greatest extent possible maximize the fulfillment of desires. For the individual, consumption that alleviates desire is a moral act. In contrast, repression (including self-repression) of desires and their fulfillment stands in the way of human progress, and is immoral, signaling a need for managerial liberation.

6. Homogenizing Cosmopolitan Universalism: The belief that:

a) all human beings are fundamentally interchangeable and members of a single universal community;

b) that the systemic “best practices” discovered by scientific management are universally applicable in all places and for all people in all times, and that therefore the same optimal system should rationally prevail everywhere;

c) that, while perhaps quaint and entertaining, any non-superficial particularity or diversity of place, culture, custom, nation, or government structure anywhere is evidence of an inefficient failure to successfully converge on the ideal system; and

d) that any form of localism, particularism, or federalism is therefore not only inefficient and backwards but an obstacle to human progress and so is dangerous and immoral. Progress will always naturally entail centralization and homogenization.

7. Abstraction and Dematerialization: The belief, or more often the instinct, that abstract and virtual things are better than physical things, because the less tied to the messy physical world humans and their activities are, the more liberated and capable of pure intellectual rationality and uninhibited morality they will become.

Practically, dematerialization, such as through digitalization or financialization, is a potent solvent that can help burn away the repressive barriers created by attachments to the particularities of place and people, replacing them with the fluidity and universality of the cosmopolitan. Dematerialization makes property more easily tradable, and can more effectively produce homogenization and fulfill desires at scale. Indeed in theory dematerialization could allow almost everything to take on and be managed at vastly greater, even infinite, mass and scale, holding out the hope of total efficiency: a state of pure frictionlessness, in which change (progress) will be effortless and limitless. Finally, dematerialization also most broadly represents an ideological belief that it is the world that should conform to abstract theory, not theory that must conform to the world.

This managerial system developed into several overlapping, interlinked sectors that can be roughly divided into and categorized as: the managerial state, the managerial economy, the managerial intelligentsia, the managerial mass media, and managerial philanthropy. Each of these five sectors features its own slightly unique species of managerial elite, each with its own roles and interests. But each commonly acts out of its own interest to reinforce and protect the interests of the other sectors, and the system as a whole. All of the sectors are bound together by a shared interest in the expansion of technical and mass organizations, the proliferation of managers, and the marginalization of non-managerial elements.

The managerial state, characterized by its proliferating administrative bureaucracies and thirst for centralized technocratic control, has a strong incentive to launch utopian and meliorist schemes to “liberate” and reorganize more and more portions of society (the theoretical bases for which are pumped out by the managerial intelligentsia), necessitating entire new layers of bureaucratic management (and whole new categories of “experts”).

Meanwhile the managerial corporation also has a great deal to gain from the project of mass homogenization, which allows for greater scale and efficiencies (a Walmart in every town, a Starbucks on every corner, Netflix and Amazon accessible on the iPhone in every pocket) by breaking down the differentiations of the old order. The state, which fears and despises above all else the local control justified by differentiation, is happy to assist. The managerial economy also gains directly from the stimulation of greater consumer demand produced by the liberation of the masses from the repressive norms of the old bourgeois moral code and the encouragement of hedonistic alternatives – as thought up by the intelligentsia, advertised by the mass media, and legally facilitated by the state.

Mass media, too, has an interest in homogenization, allowing the entertainments and narratives it sells to scale and reach a larger and more uniform audience. Mass media, already an outgrowth of journalism’s integration with the mass corporation, also has an incentive to integrate itself with both the intelligentsia and the state in order to gain privileged access to information; the intelligentsia meanwhile relies of the media to affirm their prestige, while naturally the state has an incentive to fuse with the media to effectively distribute the chosen information and narratives it wants to reach the masses.

As the old bottom-up network of extended families, social associations, religious congregations, neighborhood charities, and other institutions of grass-roots bourgeois community life are broken down by the managerial system, managerial philanthropy – funded by the wealth produced by the managerial economy and offering the elite a means to transform that wealth into social power tax free – is eager to fill the void with a crude simulacrum, offering top-down philanthropic initiatives, managerial non-profit grifts, and astroturfed activist movements in their place.

These inevitably work to spread managerial ideology and the utopian social engineering campaigns of the state, further disrupting the bourgeois order. The breakdown of that order then inevitably only produces more social problems, which in turn provide new opportunities for managerial philanthropy to offer “solutions.”

The ideological pronouncements of the intelligentsia, transmitted to the public as revealed truth (e.g. “the Science”) by the managerial mass media, serve to normalize and justify the schemes of the state, which in turn gratefully supports the intelligentsia with public money and programs of mass public education, which funnel demand into the intelligentsia’s institutions and also help to fund the research and development of new technologies and organizational techniques that can further expand managerial control.

This served a straightforward purpose. Political theorists since Aristotle have recognized that “a numerous middle class which stands between the rich and the poor” is the natural bedrock of any stable republican system of government, resisting both domination by a plutocratic oligarchy and tyrannical revolutionary demands by the poorest. By eliminating this class, which had been the powerbase of his Nationalist rivals, Mao paved the way for his intelligentsia-led Marxist-Leninist revolution to dismantle every remaining vestige of republican government, replace the old elite with a new one, and take total control of Chinese society.

And yet – if you’ve been following along so far – China, with its vast techno-bureaucratic socialist state, is still recognizably a managerial regime. More precisely, China is a hard managerial regime.

Ever since the political philosopher James Burnham published his seminal book The Managerial Revolution in 1941, theorists of the managerial regime have noted strong underlying similarities between all of the major modern state systems that emerged in the 20th century, including the system of liberal-progressive administration as represented at the time by FDR’s America, the fascist system pioneered by Mussolini, and the communist system that first appeared in Russia and then spread to China and elsewhere. The thrust of all of these systems was fundamentally managerial in character. And yet each also immediately displayed some, uh, quite different behavior. This difference can, however, be largely explained if we distinguish between what the political theorist Sam Francis classified as soft and hard managerial regimes.

The character of the soft managerial regime is that described in the previous section. In contrast, a hard managerial regime differs somewhat in its mix of values. Hard managerial regimes tend to reject two of the seven values of the (soft) managerial ideology described above, discarding hedonism and cosmopolitanism (though homogenization and centralization remain a priority). Instead they tend to emphasize managing the unity of the collective (e.g. the volk, or “the people”) and the value that individual loyalty, strength, and self-sacrifice provides to that collective.[4]

Most importantly, hard and soft managerial regimes differ in their approach to control. Hard managerial regimes default to the use of force, and are adept at using the threat of force to coerce stability and obedience. The state also tends to play a much more open role in the direction of the economy and society in hard systems, establishing state-owned corporations and taking direct control of mass media, for example, in addition to maintaining large security services. This can, however, reduce popular trust in the state and its organs.

In contrast, soft managerial regimes are largely inept and uncomfortable with the open use of force, and much prefer to instead maintain control through narrative management, manipulation, and hegemonic control of culture and ideas. The managerial state also downplays its power by outsourcing certain roles to other sectors of the managerial regime, which claim to be independent. Indeed they are independent, in the sense that they are not directly controlled by the state and can do what they want – but, being managerial institutions, staffed by managerial elites, and therefore stakeholders in the managerial imperative, they nonetheless operate in almost complete sync with the state. Such diffusion helps effectively conceal the scale, unity, and power of the soft managerial regime, as well as deflect and defuse any accountability. This softer approach to maintaining managerial regime dominance may lead to more day-to-day disorder (e.g. crime), but is no less politically stable than the hard variety (and arguably has to date proved more stable).

Part II: Making the Demos Safe for Democracy

After the uprising of the 17th June

The Secretary of the Writers Union

Had leaflets distributed in the Stalinallee

Stating that the people

Had forfeited the confidence of the government

And could win it back only

By redoubled efforts. Would it not be easier

In that case for the government

To dissolve the people

And elect another?

– Bertolt Brecht, “The Solution” (1953)

“In the great debate of the past two decades about freedom versus control of the network, China was largely right and the United States was largely wrong.” So declared neoconservative lawyer and former Bush administration Assistant Attorney General Jack Goldsmith in a high-profile 2020 essay on democracy and the future of free speech for The Atlantic magazine. “Significant monitoring and speech control are inevitable components of a mature and flourishing internet, and governments must play a large role in these practices to ensure that the internet is compatible with a society’s norms and values,” he explained. “The private sector’s collaboration with the government in these efforts, are a historic and very public experiment about how our constitutional culture will adjust to our digital future.”

Back in the year 2000, President Bill Clinton had mocked the Chinese government’s early attempts to censor free speech on the internet, suggesting that doing so would be “like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall.” By the time Goldsmith’s take was published in the flagship salon of the American ruling class two decades later, such scorn had been roundly replaced by open admiration. Beginning immediately after the 2016 election of Donald Trump, and then accelerating exponentially in 2020, America’s elite class began regularly arguing, as did The New York Times Emily Bazelon, that the country was “in the midst of an information crisis” producing “catastrophic” risks of harm, and that actually, “Free speech threatens democracy as much as it also provides for its flourishing.” The American people would have to accept their free speech rights being curtailed for their own good.

Thousands of American intellectuals became “disinformation” experts overnight. In coordination with these academics and NGOs, mass media leapt to set up “fact checking” operations to arbitrarily declare what was and was not true, selling the public a tall-tale of foreign meddling and dark tides of online “hate” that conveniently justified having their burgeoning independent competition deplatformed from the internet.

The advent of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 was then seized upon as a reason to double-down on this attack on the public. As Jacob Siegel recently documented in a magisterial account of the origins of the “war on disinformation,” the managerial state quickly re-oriented all the tools, techniques, and swollen bureaucratic automatons it had developed to fight the “Global War on Terror” in order to begin waging a counterinsurgency campaign against its own citizens.

Something had changed in the calculus of America’s elites. Traditionally at least vaguely liberal, their seemingly abrupt U-turn on the value of free speech and deliberative democracy represents a paradigmatic example of a process enacting a final replacement of old order classical liberalism with an open embrace of total technocratic managerialism – one that we will explore in more detail soon. But what exactly prompted this sudden shift?

Former CIA analyst Martin Gurri has coined the term “revolt of the public” to describe the ongoing phenomenon in which, around the world, the authority and legitimacy of elite institutions has collapsed as the digital revolution has undermined traditional elite gatekeepers’ ability to fully control access to information and monopolize public narratives. This decline of hierarchical gatekeepers (such as legacy media) has helped to expose elite personal, institutional, and policy failures, as well as widespread corruption and the broader reality that the managerial system itself functions with little-to-no real public input or accountability. This has helped fuel public frustration and anger with the endemic and mounting problems of the status quo, mobilizing insurgent political movements to present democratic challenges to the establishment.

But, for the managerial elite, the character of this revolt is even more threatening than Gurri’s summation implies. In the West, this underdog public rebellion is not only directed against the ruling managerial technocracy, but, critically, has been conducted by precisely the managerial elite’s historic class enemies: the remnants of the old bourgeois middle class.

For the managerial elite this was the apparition of a terrifying nightmare. They thought they’d broken and cast down the old order forever. Now it seemed to be trying to climb out of the grave of history, where it belonged, to take its revenge and drag them all back to the dark ages before enlightened managerial rule had brought the word of progress to the world. The prospect of real power returning to the hands of their traditional enemies appeared to be a mortal threat to the future of the managerial class.

Across the West, the managerial elite therefore immediately went into a frenzy over the danger allegedly presented by “populism” and launched their own revolt, declaring a Schmittian state of exception in which all the standard rules and norms of democratic politics could be suspended in order to respond to this existential “crisis.” In fact, some began to question whether democracy itself might have to be suspended in order to save it.

“It’s Time for the Elites to Rise Up Against the Ignorant Masses,” New York Time Magazine journalist James Traub thundered with an iconic 2016 piece in Foreign Policy magazine. This quickly became a view openly and proudly embraced among the managerial elite, who no longer hesitated to express their frustration with democracy and its voters. (“Did I say ‘ignorant’? Yes, I did. It is necessary to say that people are deluded and that the task of leadership is to un-delude them,” Traub declared.) “Too Much Democracy is Killing Democracy,” is how a 2019 article published by neocon rag The Bulwark put it, arguing for Western nations to take their “bitter technocratic medicine” and establish “a political, social, and cultural compact that makes participation by many unnecessary.”

This elite revolt against democracy cannot be fully understood as a reaction only to proximate events, however – no matter how outrageously orange and crude their apparition. Rather, the populist revolts that emerged in 2016 sparked such an intense, openly anti-democratic reaction because they played directly into a much deeper complex of managerial anxieties, dreams, and obsessions that has roots stretching back more than a century.

Democracy and “Democracy”

It was 1887 and Woodrow Wilson thought America had a problem: too much democracy. What it needed instead was the “science of administration.” “The democratic state has yet to be equipped for carrying those enormous burdens of administration which the needs of this industrial and trading age are so fast accumulating,” the then-young professor of political science wrote in what would become his most influential academic work, “The Study of Administration.”

Deeply influenced by Social Darwinism and eugenics,[5] vocal in his contempt for the idea of being “bound to the doctrines held by the signers of the Declaration of Independence” (“a lot of nonsense… about the inalienable rights of the individual”), and especially impatient with the Constitution’s insistence on the idea of “checks and balances,” Wilson believed the American state needed to evolve or die. For too long it had been “saddled with the habits” of constitutionalism and deliberative politics; now the complexity of the world was growing too great for such antiquated principles, which were “no longer of more immediate practical moment than questions of administration.”

Asserting the urgent need for “comparative studies in government,” he urged America’s leadership class to look around the world and see that, “Administration is everywhere putting its hands to new undertakings,” and, “The idea of the state and the consequent ideal of its duty are undergoing noteworthy change.” America had to change too. “Seeing every day new things which the state ought to do, the next thing is to see clearly how it ought to do them,” he wrote. Simple as.

But what did Wilson mean by “administration” anyway? “Administration lies outside the proper sphere of politics,” he wrote. “Administrative questions are not political questions.” By this he meant that all the affairs of the modern state, all the “new things the state ought to do,” should be placed above any vulgar interference from the political – that is, above any democratic debate, choice, or accountability – and instead turned over to an elevated class of educated men whose full-time “profession” would be governing the rabble. What Wilson explicitly proposed was rule by the “universal class” described by Hegel: an all-knowing, all-beneficent class of expert “civil servants,” who, using their big brains and operating on universal principles derived from Reason, could uniquely determine and act in the universal interest of society with far more accuracy than the ignorant, unrefined masses.

For Wilson, the Prussian system represented the best possible model for maximizing the march of progress. Parliamentary yet authoritarian, it combined the most enlightened economic and social advances of the time – the first welfare state, mass education programs, and a state-led Kulturkampf (“Culture War”) against the Catholic Church and all the backwards forces of reaction – with political certainty, stability, and efficiency. Most importantly, it had developed a professional bureaucracy (i.e. an “administration”) of managers handed the power and leeway to guide the country’s development along rational, “scientific” lines. Wilson would, two decades later, have the opportunity to begin imposing something like this model on America.

Campaigning in part on a promise to employ the power of government on behalf of what he advertised as the “New Freedom” of universal social justice, Wilson wormed his way into power in 1912 as the first and fortunately only political science professor ever elected President of the United States.[6] He fittingly rode to office on the back of the new American Progressive Movement, which had eagerly modeled itself on the then fashionable Progressive Party of Germany. An innovative political alliance, the new party had cunningly brought Germany’s corporate power-players together with state bureaucrats and academic intelligentsia (together nicknamed the Kathedersozialisten, or “socialists of the endowed chair”), uniting them to push forward the kind of top-down social and economic reforms they all stood to benefit from. Wilson’s hope for America to look to the German model for inspiration was thus fulfilled.

Over the course of his presidency (1913-1921), and seizing in particular on the opportunity provided by the crisis of WWI, Wilson would oversee the first great centralizing wave of America’s managerial revolution, establishing much of the initial basis for the country’s modern administrative bureaucracy, including imposing the first federal income tax and creating the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Trade Commission, and the Department of Labor.[7]

He also ruled as perhaps the most authoritarian executive in American history, criminalizing speech through his Espionage and Sedition acts, implementing mass censorship through the Post Office, setting up a dedicated propaganda ministry (The Committee on Public Information), and using his Attorney General to widely prosecute and jail his political opponents. More dissidents were arrested or jailed in two years of war under Wilson than in Italy under Mussolini during the entirety of the 1920s.

But Wilson’s most important legacy was to begin the process to “organize democracy” in America just as he’d dreamed of doing as an academic: a “universal class” of managers would henceforth determine and govern on behalf of the people’s true will; democracy would no longer to be messy, but made steadily more managed, predictable, and scientific. From this point forward the definition of democracy itself would begin to change: “democracy” no longer meant self-government by the demos – the people – exercised through voting and elections; instead it would come to mean the institutions, processes, and progressive objectives of the managerial civil service itself. In turn, actual democracy became “populism.” Protecting the sanctity of “democracy” now required protecting the managerial state from the demos by making governance less democratic.

Today this vision of “managed democracy” (also known as “guided democracy”), is a form of government much lusted after by elites around the world, having succeeded (in its more benevolent incarnations) in establishing orderly regimes in countries like Singapore and Germany, where the people still get to vote but real opposition to the steamroller of the state’s agenda isn’t tolerated. In such a system the people are offered the satisfaction of their views having been “listened” to by their political-administrative class, but said views can always be noted and dispensed with if they are a danger to “democracy” and its interests. Here Wilson’s old question of how “to make public opinion efficient without suffering it to be meddlesome” seems to have found a solution.