To get a better perspective on the ongoing instability in Manipur, turn your attention to catastrophic crises in Myanmar

Ritual incantation of ‘Meitei majoritarianism’ won’t take us closer to the truth, or provide a lasting solution

Sreemoy Talukdar

July 21, 2023

To get a better perspective on the ongoing instability in Manipur, turn your attention to catastrophic crises in Myanmar

People from Manipur participate in candle light vigil demanding peace and to raise concern over the current conflicts in Manipur, at Mukundapur in Kolkata on 17 June, 2023. PTI

External affairs minister S Jaishankar recently returned from a week-long trip to Indonesia and Thailand. In Jakarta, Jaishankar took part in a clutch of meetings with his East Asian counterparts under ASEAN-India, East Asia Summit and ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) frameworks.

He also took time out to meet Chinese state councillor and foreign minister Wang Yi, US secretary of state Antony Blinken, Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov and European Union’s foreign policy chief Josep Borrell. While these meetings and pull-asides expectedly dominated the headlines, it is the second leg of Jaishankar’s trip that went under-noticed but demands greater attention.

In Bangkok, advancing India’s Neighbourhood First and Act East policies, Jaishankar co-chaired the Mekong Ganga Cooperation (MGC) meeting and attended the BIMSTEC foreign ministers’ retreat. Founded in 2000, the MCG framework brings together India, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, and Myanmar — a pariah nation in high-level ASEAN summits owing to the junta’s lack of progress on the ‘five-point peace plan’.

Myanmar military’s 2021 coup d’état has completely upended regional diplomacy, turned the Southeast Asian nation into a restive state beset with violent crackdown on anti-junta protestors, ethnic rivalry and civil war, and has brought a simmering crisis bang on India’s doorstep, affecting the sensitive northeastern states.

As we shall presently see, the catastrophic incidents in Myanmar, coupled with America-led West’s grave and repeated policy failures, have not only complicated India’s dynamics with Naypyitaw, but have also led to a complex chain of events leading to an explosion of ethnic violence in Manipur that New Delhi is struggling to control.

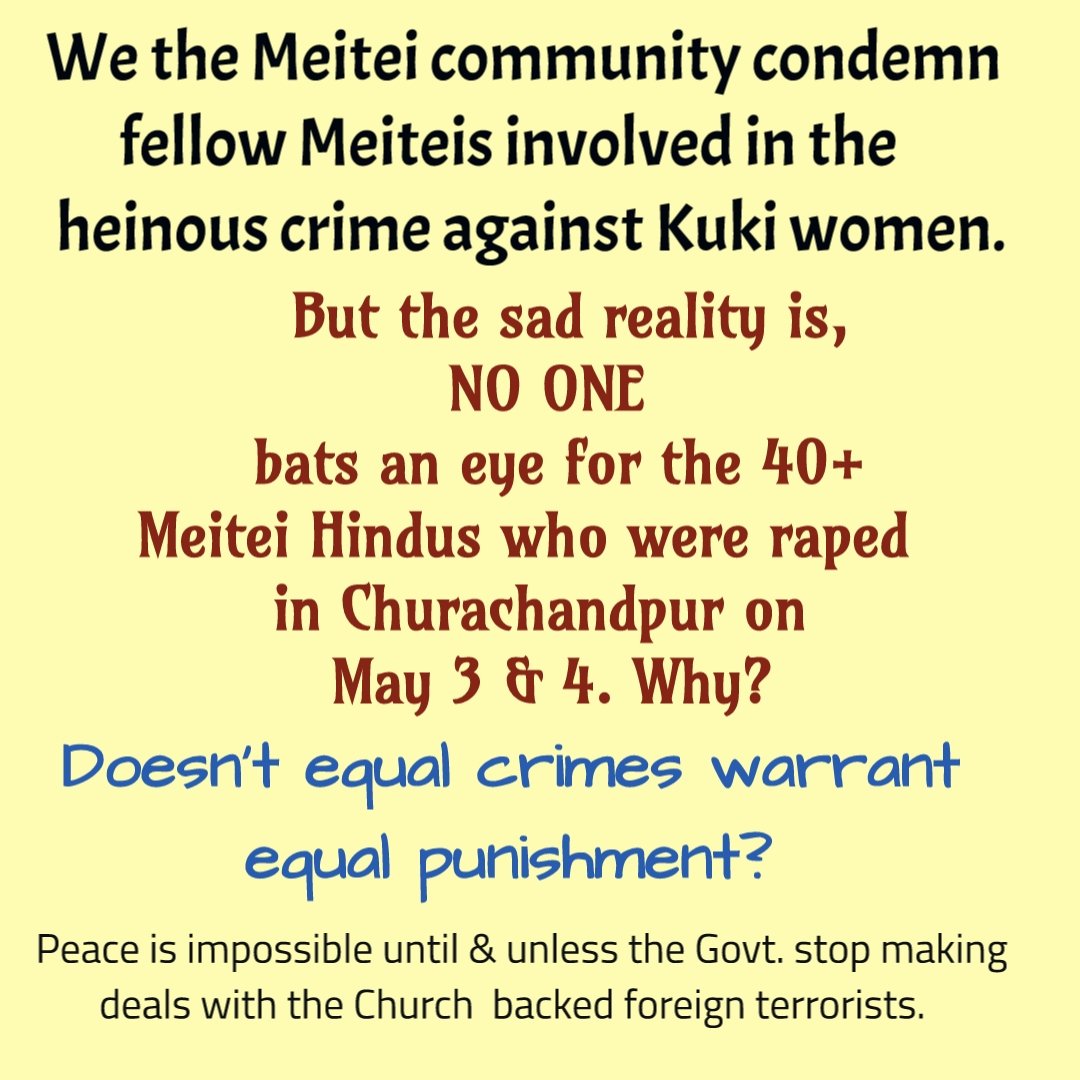

If the Kuki and Meitei communities are pitted against each other in an orgy of retributive violence since May, then the administration must share the lion’s share of the blame. It is equally true that confirmation bias has become normalised in media commentaries. Contrary to popular discourse, the Manipur crisis isn’t one-dimensional, nor are the painful developments occurring in medias res.

(in medias res (Classical Latin: [ɪn ˈmɛdɪ.aːs ˈreːs], lit. "into the middle of things"))

To get a better perspective on the factors destabilizing the key northeastern state — eschewing the blind-men-and-elephant syndrome — we need to turn our attention to the multifaceted crises unfolding in dysfunctional Myanmar, the military-ruled, conflict-torn nation that shares a 1,700km-long frontier with four Indian states, including a 400km unfenced, permeable border with Manipur.

ASEAN may deny Myanmar a seat at the table. India doesn’t have that luxury. It wasn’t a surprise to note Jaishankar take time out in Bangkok to meet the foreign minister from Myanmar’s military-led government, U Than Swe, on the sidelines of the MCG summit on Sunday.

During the scarce bilateral, Jaishankar raised several critical issues with his counterpart, including the India-Myanmar-Thailand trilateral highway, the stalled project that India is finding “very difficult” to execute, “the humanitarian situation in Myanmar”, on which the minister “proposed people-centric initiatives aimed to address the pressing challenges”. As Jaishankar noted on Twitter, “India supports the democratic transition process in Myanmar and highlights the need for return of peace and stability. We will closely coordinate our policy with ASEAN in this regard.”

During his meeting with Than Swe, Jaishankar also “underlined the importance of ensuring peace and stability in our border areas.” In language that is unusually strong for a former career diplomat known to be frugal and judicious with words, the minister said India’s border areas have been “seriously disturbed recently and any actions that aggravate the situation should be avoided”.

The minister’s words reflect India’s anxiety over the turn of events in Myanmar that have added to the instability in Manipur. Underlining the complexity of the issues involved, Jaishankar said he also “flagged concerns about human and drug trafficking” and “urged stronger cooperation among relevant parties for the early return of trafficked victims.”

To put this in perspective, Jaishankar’s meeting with Than Swe followed India’s defence secretary’s recent two-day official visit to Myanmar, during which Giridhar Aramane called on key figures in the ruling junta’s State Administrative Council (SAC). His engagements included meetings with the military regime chief, Gen Min Aung Hlaing, defence minister Gen (Retd.) Mya Tun Oo, commander-in-chief, Myanmar Navy, Admiral Moe Aung and chief of defence industries Lt Gen Khan Myint Than.

In a press statement released on 1 July, India’s defence ministry said: “the two sides discussed issues related to maintenance of tranquillity in the border areas, illegal trans-border movements and transnational crimes such as drug trafficking and smuggling. Both sides reaffirmed their commitment to ensure that their respective territories would not be allowed to be used for any activities inimical to the other.”

Two questions arise. One, why is trans-border movement in focus? Two, with Manipur burning, why are Indian ministers and high-ranking officials engaging with Myanmar?

We get an inkling of the answers and a sense of India’s urgency when we note that Aramane was accompanied by a delegation of officials from the ministries of defence, external affairs and armed forces, and as Indian Express reports, “support to the valley based insurgent groups, the inflow of arms to rioters and tacit external support compounding the lawlessness in the state were also on the agenda for discussions.” The newspaper further reports, quoting sources, that “the timing of the visit is significant with increasing narcotics smuggling and drug trafficking from Myanmar since ethnic clashes broke out in Manipur in May.”

The destabilizing factor of armed insurgents from Myanmar — many of whom have kinship ties with transnational ethnic communities straddling India and its immediate neighbours — slipping into the northeastern states through the porous border and adding to the complexity of Kuki-Meitei clashes and exacerbating the ongoing conflict in Manipur, has been under-reported.

To escape the crackdown by Myanmar’s military regime, ethnic Kuki-Chin people have entered India by thousands since the coup in 2021. According to figures from UNHCR, the refugee agency of the United Nations, the ongoing civil war in Myanmar has displaced 1,827,000 people since February 2021, among which over 53000, mostly from the conflict-ridden Chin state and Sagaing region of Myanmar — the hotbed of armed resistance against the junta — have entered India’s northeastern states of Mizoram and Manipur till the month of May 2023.

The volatile situation in Myanmar has created a breeding ground for a spate of armed insurgent groups operating in the grey zone between the porous India-Myanmar frontier. While groups such as PDF (People’s Defense Forces), the armed wing of Myanmar’s shadow National Unity Government, primarily carry out hit-and-run attacks against the military junta, some also act against India’s interests.

What has complicated the situation further for India is that the Myanmar military, desperate to tackle the anti-junta forces and ethnic armed organizations, has reportedly reached an understanding with some anti-India insurgency groups “to assist junta forces in their operations against PDFs in the so-called ‘liberated zones’ such as Chin State and Sagaing Region.”

As Washington DC-based think tank USIP observes in a report, “far from denying territory to Indian rebels, the junta is offering them sanctuary in Myanmar in return for fighting the pro-democracy People’s Defense Forces and ethnic revolutionary organizations (EROs) in Sagaing Region” and rebel groups such as The People’s Liberation Army of Manipur, in turn, are using “Myanmar territory as a staging ground for attacks in India.”

If the conflict has spilled over onto India’s borders, a part of the blame must also go to the US-led West whose policy failures have a direct bearing on India’s national security. The West’s economic sanctions on the Southeast Asian nation may have done little to force the ruling military junta into restoring democracy, but it has made life miserable for citizens, opened the door wide for China to increase its influence and created the perfect atmosphere for intensification of political dislocation and civil war in Myanmar.

America’s policy failures have worsened the Myanmar crisis in two ways. One, wave after wave of debilitating sanctions (the US has imposed 20 rounds targeting key figures of the military junta, defence ministry, business entities, state-owned enterprises and brokers while the European Union and the UK have imposed six separate rounds) have triggered a meltdown in Myanmar’s economy. Investors have been spooked away, unemployment rates have shot up while the currency has suffered a collapse.

As the Diplomat notes in a report, “nearly 40 percent of the total working-age population (in Myanmar) are out of work, while almost half of households reported a decrease in incomes over the past year, compared to just 15 percent reporting the reverse. The World Bank also cited a survey from May that found 48 percent of farming households worry about not having enough food to eat, up from about 26 percent the year before.”

The military junta, that has been targeted by American sanctions regime for decades until Barack Obama reversed the course, has shaken off the restrictions with ease, but the punitive measures have left the US with no leverage over the Tatmadaw.

In the absence of any concurrent engagement mechanisms, as geostrategist Brahma Chellaney writes in The Strategist, American “interventions are likely to plunge Myanmar into greater disorder and poverty without advancing US interests. Even in the unlikely event that the disparate groups behind the armed insurrection manage to overthrow the junta, Myanmar would not re-emerge as a democracy. Rather, it would become a Libya-style failed state and a bane to regional security. It would also remain a proxy battleground between Western powers and China and Russia.”

The second policy failure of the American state is its stated decision to back the armed insurgents operating within Myanmar that are seeking to overthrow the regime. The BURMA Act “authorizes the appropriation of funds for FY 2023 to 2027 for various forms of assistance, including ‘programs to strengthen federalism in and among ethnic states in Burma, including for non-lethal assistance for Ethnic Armed Organizations in Burma’.”

In retaliation, the regime has stepped up its brutalities in Myanmar’s Chin state and the northwestern Sagaing regions, both bordering India and offering the stiffest armed resistance to the military regime. The junta, in a massive airstrike on the resistance movement outside Pazigyi village in Sagaing region on 11 April, killed more than 100 people, including children, using deadly ‘enhanced blast’ munitions, also known as ‘vacuum bomb’.

The brutal attack forced many of the ethnic Kuki-Chin people to flee to India. Reuters reported last month, quoting Indian security officials and civil society groups that three Indian states of Mizoram, Manipur and Nagaland are currently sheltering around 16,000 people from Myanmar, “with the number expected to rise in coming months”, and leaving officials worried “that the region could become a staging post for pro-democracy activists and stoke instability.”

The influx of refugees, including armed militants, has added to the volatility in Manipur where anger has started rising over illegal infiltration and its possible effect over employment and land rights in a state where ethnic tribal groups are shaped along political and geographical divides.

According to a report in Economic Times, the violence in Manipur that has resulted in widespread arson, death, displacement and atrocities on women, is linked to militant outfits operating in Manipur that are based in Myanmar. The report quotes a senior government official, as saying, “Just see the scale of violence and mobilisations. Gun-toting people were seen killing people. If militants were not involved, the situation cannot have aggravated to such an extent.”

According to a report in the Diplomat, “In the last week of April, a random identification drive by the Manipur government as part of the population commission’s work (the commission was set up last year to track illegal immigration) identified 1,147 undocumented Myanmar nationals in 13 locations in Tengnoupal district, 881 persons in three locations in Chandel district, and 154 persons in Churachandpur district”. The report further quotes a government official, as saying, “Chandel, Tengnoupal, and Churachandpur are Kuki-dominated districts along the Myanmar border.”

During a press conference on 1 June from Imphal, post his visit to the strife-torn state, Union home minister Amit Shah said biometrics of people coming from across the border are being recorded and “for a permanent solution” to the instability in Manipur, “we have set up wired fencing across 10 kilometers of the Manipur-Myanmar border on a trial basis, work tender has been invited for fencing on another 80 kilometers, and a survey for fencing the rest of the Manipur-Myanmar border is being initiated.”

This complex web of issues behind the ethnic clashes in Manipur will remain incomplete without exploring the drug angle, a reference that has repeatedly cropped up during high-level interactions between India and Myanmar.

In his piece for The Diplomat mentioned earlier, Snigdhendu Bhattacharya quotes JNU professor Bhagat Oinam, a Meitei by ethnicity, as saying, that while Kuki-Chin ingress has happened in Manipur over decades, “what has happened over the past few years is an explosion in poppy cultivation in Manipur’s Kuki-dominated districts backed by drug cartels and insurgent groups with a cross-border network, resulting in huge loss of forest cover”, a problem that aggravated since the 2021 coup when the influx intensified due to persecution of the Kuki-Chin community by the military regime. “A section of these illegal immigrants is being used by the drug and weapon cartels in Manipur,” said the professor, according to the report.

While the Kuki groups have dismissed these allegations as insidious narratives, studies have pointed out how Myanmar has become the “largest producer of illegal drugs within the infamous Golden Triangle—a tri-junction at the Myanmar, Laos and Thailand borders” that makes its way to India through the porous border.

Supply of drugs from the Golden Triangle remains a problem. In recent times, however, poppy cultivation has proliferated in the hilly areas of Manipur. According to a report in Economic Times, “narcotics trade is playing a significant role in Manipur violence” and the drug cartels are utilizing large chunks of the hilly districts for “quality poppy cultivation”.

As Manipur shifts its status from a transit route for drugs to major producer fuelled by armed refugees from Myanmar, a report by the Netherlands-based Transnational Institute, released in December 2021, observes how “opium cultivation in Manipur seems to be more integrated within the regional drug economy and connected to other actors, notably from Myanmar.”

It is evident that while a knotty vortex of issues has contributed to the instability in Manipur, ritual incantation of “Meitei majoritarianism” to explain the unrest amounts to little more than a projection of the left-liberal ideological bias. Unless a holistic approach is adopted by the Indian state that looks at the Manipur issue in all its multifaceted complexities, a permanent solution will elude us.

Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views.