As mentioned earlier the Regional Security Outlook 2018 by the Australia based Council For Security Cooperation In The Asia Pacific carries a bunch of articles on the Belt and Road Initiative / One Bridge One Road aka BRI / OBOR by authors from India, Indonesia, Japan, Russia, US besides the PRC.

The Indian authored article by Hemant Krishan Singh and Arun Sahgal follows:

DIFFUSION OF SOFT POWER OR PURSUIT OF HEGEMONY?

AN INDIAN PERSPECTIVE

Hemant Krishan Singh and Arun Sahgal

A number of inter-related factors largely determine how the world perceives China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). First, according to Miles’ Law, where you stand depends on where you sit Thus, the security and economic perceptions of nations impacted by the BRI differ based on where each nation “sits”, its historical experience, and its own specific interests. Second, votaries of the post-1991 liberal economic order, linking “end of history” scenarios of perpetual peace with globalisation and economic interdependence, are more likely to hold benign views of the BRI. Those recognising the inevitable reprise of geopolitical competition in an era marked by a major flux in global power equations, between the West and Asia and within Asia, tend to be more sceptical. It follows that nations in West Europe, for instance, who are no longer invested in emerging Asia’s power balances, appear to embrace the BRI for its presumed business potential from which they can benefit. So, to varying degrees, do countries in the Asia Pacific and elsewhere, who are heavily “dependent” on China trade and finance. Other Asian nations who seek greater accommodation and balancing of major and emerging power interests, thereby bolstering multipolarity, a rules-based security architecture and respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, are far less sanguine about the purpose and regional impact of the BRI. That is where India “sits”.

This article provides the authors’ perspective on how India views the BRI. It is not intended to detail the various elements of the BRI, but only to deconstruct the broader strategic dimensions of the initiative, as well as to examine BRI segments that impact India. Finally, we outline India’s official response and corresponding policies towards regional connectivity. To understand the BRI, it is useful to begin by recalling a few distinctive characteristics of China’s external economic policies and the nature of its domestic economy. To begin with, as a non-free market economy, China subordinates market forces and trade relations to suit its mercantilist and national interests; the Communist Party of China (CPC) enjoys enormous power to orchestrate outcomes in the Chinese economy. Not surprisingly, China has derived asymmetric gains from the liberal economic order, which it now professes to champion. Second, maintaining the goodwill of the Chinese government is a critical precondition for the successful pursuit of trade and economic relations with China. Foreign partners have to willingly compromise their democratic values and free market principles to ensure access to China’s attractive market and finance. Failing to attach importance to China’s core interests and major concerns can swiftly attract orchestrated reprisals and painful boycotts. Japan, the Philippines, and more recently South Korea can testify to this reality. These elements, among others, have ensured China’s unprecedented and unconstrained rise to great power status. China has now become too big to fault.

With such a track record, it would be truly remarkable if the BRI represents a change of course towards an altruistic “win-win” regional development initiative, as the BRI is often projected. This is all the more so as Xi Jinping pursues nationalist “rejuvenation” and China’s geopolitical behaviour is marked by unilateral assertions of “historical” rights which are the principal cause of regional tensions in Asia today.

Now let us turn to the BRI itself. Its humbler origins appear to lie in pressures on the CPC leadership to develop China’s western provinces and, even more importantly, to counter the impact of China’s economic slowdown. The BRI has thereafter evolved into a mega project and grand strategy to integrate China’s markets, gain access to resources, utilise excess domestic capacity, strengthen China’s periphery, secure military access and enlist “all-weather friends”. The BRI is a unilaterally conceived national initiative designed to align the economic and strategic landscape from Eurasia to East Asia, Southeast Asia to South Asia, to China’s singular advantage. It most certainly is not a multilaterally structured or negotiated initiative. Significantly, all strands of the BRI have a backward linkage to China alone in terms of economic benefit.

It is well recognised that the BRI lacks a formal institutional structure and that there is lack of transparency about BRI decision making. Essentially, the initiative is propelled by bilateral agreements between China and enlisted countries under which Chinese companies gain preferential access to low/medium cost economies that need capital to upgrade their infrastructure. Investment decisions, generally announced as outcomes of highlevel visits by China’s leaders, emanate from collusive political understandings with national elites, flowing from which projects are awarded to major Chinese companies without competitive bidding. The average rate of interest of Chinese loans for the BRI is significantly higher than multilateral financing from institutions such as the ADB.

Overall, these elements reflect China’s revisionist pursuit of preferential, non-competitive and exclusionary arrangements that propel its ambitions to create economic dependencies, gain political influence and eventually impose hegemonic power.

Finally, the BRI is closely linked to China’s core security objectives that include enhancing its strategic periphery through the consolidation of relations with immediate neighbours. The different strands of BRI’s continental (Silk Road Economic Belt) and oceanic (Maritime Silk Road) corridors enable China to wield military power by creating arteries for force projection.

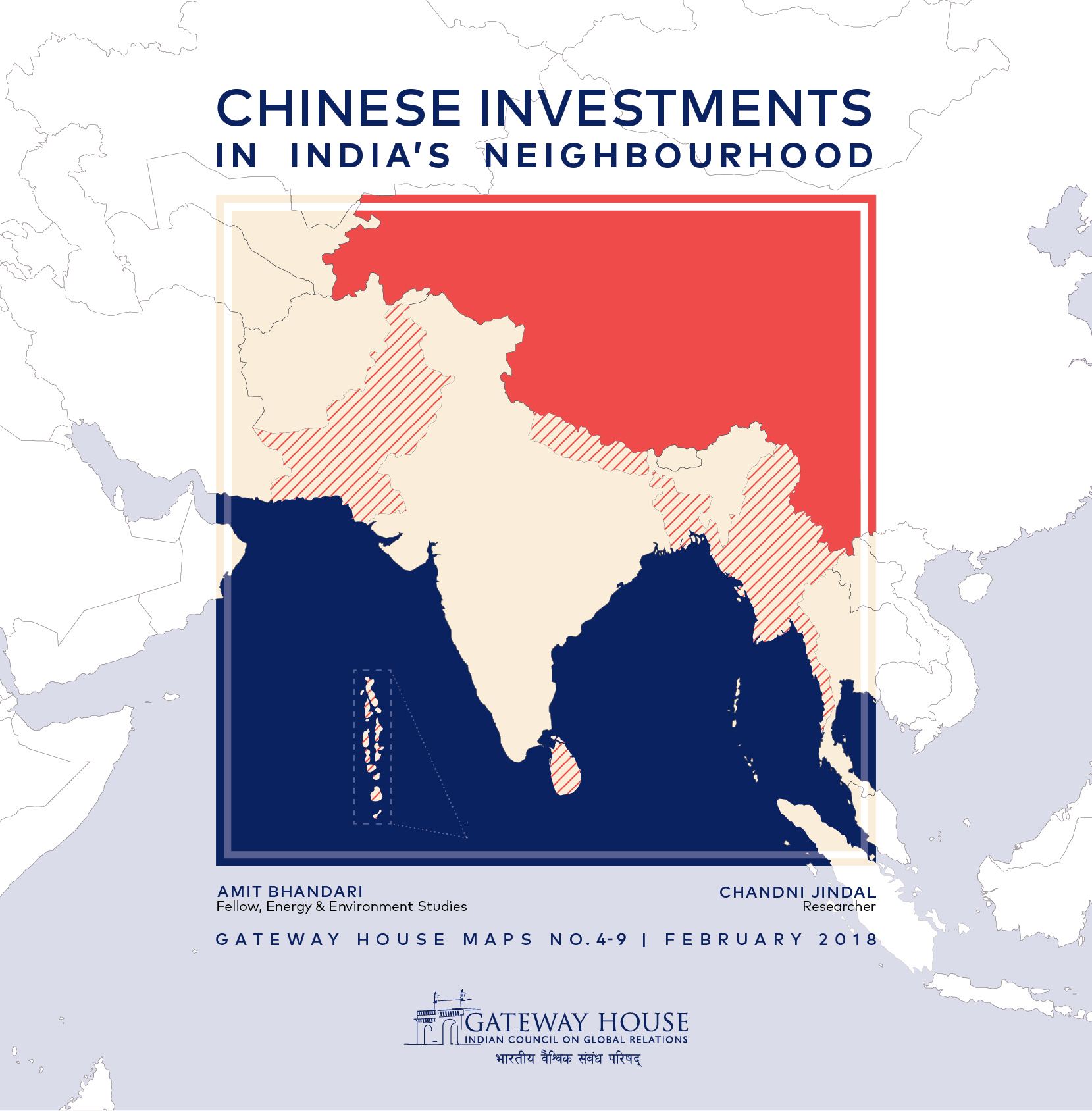

For the geo-strategist, the BRI combines Mahan’s recipe for global domination through control of the seas with Mackinder’s prescription that such domination requires control of the “heartland”. The BRI is the economic face of a grand strategy to leverage China’s soft and hard power to gain hegemony over Mackinder’s “world island”. It is also part and parcel of China’s “revitalisation” dream and the creation of a world order with “Chinese characteristics.” Now let us turn our attention to aspects of the BRI which impact India. To begin with, it is noteworthy that no element of the BRI seeks to provide direct connectivity between China and India, even though BRI segments include terrestrial components to the west (CPEC) and the east (BCIM) of India, while the MSR encircles India in the maritime domain of the Indian Ocean where India is dominant because of its geographical location. There could be two main reasons for this. The India-China boundary is not settled and China appears inclined to keep the dispute alive as coercive leverage. Second, provisioning of major connectivity, even in small pockets where the boundary is in fact mutually accepted, such as the Indian state of Sikkim, carries the potential for democratic India’s soft power to trickle back into restive and subjugated Tibet. Given Tibet’s remoteness and meagre population, the focus of China’s connectivity infrastructure inside Tibet is largely related to its security interests and defence posture.

CPEC is unquestionably the centrepiece of the BRI, carrying the promise of some $62 billion in loans and grants, of which $14 billion has already been committed. While power plants comprise a major component of CPEC, it is in fact a broadbased initiative to boost Pakistan’s domestic economy, create maritime equities adjacent to the Persian Gulf and provide strategic linkage to the restive Xinjiang province. According to a report published in the major Pakistani paper Dawn in May 2017, the CPEC master plan calls for “a deep and broadbased penetration of most sectors of Pakistan’s economy as well as its society by Chinese enterprises and culture.” CPEC is thus designed to secure a major stake in Pakistan’s transportation, communications and energy infrastructure; trade and commerce; agriculture; media; and defence (China is already Pakistan’s largest supplier of military hardware). Whether CPEC will be a “game changer” that re-orients a de-globalising Pakistan towards developmental pursuits and away from its Islamist predilections, or “game over” for that country, remains to be seen. Thus far, elements among the Pakistani elites appear to be enthused, while the general public remains largely unmoved and the military holds the key. The stakes are steadily rising as China gets increasingly involved with the domestic affairs of Pakistan. India has already made it clear, officially, that the CPEC violates India’s territorial sovereignty in Jammu & Kashmir. China’s growing military presence in Pakistan occupied Kashmir is a cause of considerable security concern for India. In terms of regional transit and connectivity, India’s historic access routes to its natural hinterland in Central Asia and West Asia have been disrupted by Pakistan since 1947. There is no indication of any Chinese efforts to press their “iron brother” Pakistan to grant India normal trade and transit rights across Pakistani territory. The CPEC delivers strategic depth for China in Pakistan but only continued access denial and strategic containment for India.

To India’s east, the BCIM corridor makes even less economic sense, as it would provide one-sided advantages to China in terms of market access to Myanmar, Bangladesh and India as well as strategic access to the Bay of Bengal. Besides, the corridor would pass through India’s security sensitive Northeast, where China lays territorial claim to large parts of Arunachal Pradesh. Apart from India’s concerns about BCIM, Myanmar too is wary about such instruments of Chinese penetration.

MSR, the maritime component of the BRI, is substantially linked to bolstering China’s security presence in the Indian Ocean. This includes China’s unprecedented naval expansion, increased naval deployments in the Indian Ocean, operationalisation of its first overseas base at Djibouti (with Gwadar more than likely destined to be the second) and creation of a host of logistic support facilities in the form of MSR ports surrounding India. China is undertaking a massive expansion of PLAN amphibious capability, increasing the size of its marine corps fivefold to 100,000 personnel, and modifying its laws to permit deployment of security personnel abroad. There is very good reason for India to closely monitor MSR inroads in the Indian Ocean.

Despite enormous Chinese pressure and warnings of adverse consequences, India declined to attend the BRI Forum held in Beijing on May 14-16, 2017. In an official statement made on May 13, 2017 India announced that connectivity initiatives must be based on “universally recognised international norms, good governance, rule of law, openness, transparency and equality;” must follow the principles of financial responsibility as well as environmental sustainability; and must be pursued in a manner that respects sovereignty and territorial integrity. The statement went on to remind Beijing that “… we have been urging China to engage in meaningful dialogue on its connectivity initiative, ‘One Belt, One Road’ which was later renamed as ‘Belt and Road Initiative’. We are awaiting a positive response from the Chinese side”. That this response has not been forthcoming for the past two years speaks for itself. From the overall Indian perspective, the fact is that with an obstructionist Pakistan to India’s west and a disputed boundary with China to its north and east, the BRI holds little promise.

Taking into account these geopolitical realities, India is shaping its own approach towards its strategic neighbourhood, based on the conviction that both historically and geographically, India is well placed to champion the “connectivity” cause as a pivotal power of Asia. India’s reference to universally recognised norms and respect for sovereignty of regional states draws direct linkages between initiatives for physical connectivity and the quest for regional peace and stability. India’s official discourse rejects any connotation that its connectivity vision is premised on geopolitical competition. It follows that for Indian policymakers, connectivity initiatives must be collaborative rather than exclusionary.

Accordingly, India’s own connectivity outreach is being structured through rules based, demand and consensus driven, bilateral or multilateral frameworks such as BBIN and BIMSTEC, or the newly launched Asia-Africa Growth Corridor (AAGC). With the closer alignment of India’s Act East Policy and Japan’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy, Japan has emerged as India’s preferred partner for translating their shared vision for Indo-Pacific connectivity into reality.

Conclusion

The BRI is an integral part of China’s grand strategy to enhance strategic influence and reach; BRI projects are essentially “China First” initiatives with backward connections to China. The BRI has no India-China component.

India’s interests are best served by its unimpeded maritime access to the Indian Ocean and the extension of ongoing programmes for domestic connectivity and port infrastructure development, to eastward connectivity between India’s northeast and South-East Asia. The announcement of the Japan-India Act East Forum to drive this process forward on September 14, 2017 is the latest pointer in that direction.

Hemant Krishan Singh,Director General, Delhi Policy Group

Arun Sahgal, Senior Fellow, Delhi Policy Group.

From here:

CSCAP Regional Security Outlook 2018