Howitzers, Rockets, & Missiles

Howitzers, Rockets, & Missiles

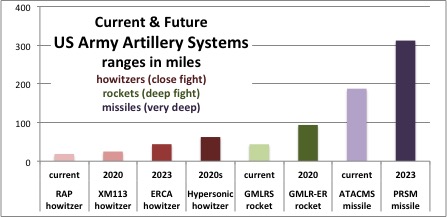

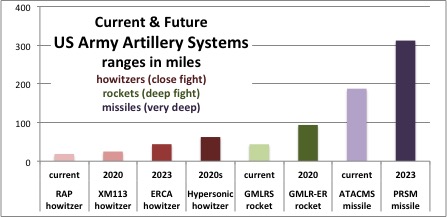

Different kinds of combat call for different weapons. Rather than invest in a single Long-Range Precision Fires system to rule them all, the Army is modernizing three,some under existing programs of record and some under Brig. Gen. Maranian’s CFT:

155 cannon, the cheapest option, for the close fight against the enemy’s frontline forces;

guided rockets for the deep fight against enemy reinforcements and supply lines; and

missiles, the most expensive munitions, for very deep or even strategic strikes against targets in the enemy rear and homeland.

Cannon shells have advanced dramatically in recent decades, with precision-guided Excalibur rounds and Rocket Assisted Projectiles to boost range. The current RAP fired from the current 155 mm howitzer can hit targets about 30 km (19 miles) away.

Even before Chief of Staff Milley made Long Range Precision Fires his No. 1 priority, the Army was working on Extended Range Cannon Artillery. ERCA has two aspects. First, the service is developing a new rocket-boosted shell, the XM113, with a 40 km range when fired from current cannon. The XM113 is now in testing, Maranian said: “We’ll see that in the hands of soldiers in about two to two-and-a-half years.”

Second, ERCA is lengthening the barrel of the howitzer by almost 50 percent (from 39 calibers to 58). The longer barrel is a harder to manufacture and more awkward to maneuver, but it lets the propellant push the shell longer, building up speed. The extended barrel should enter service in 2023, Maranian said, and combining the new ammunition with the new barrel and a new propellant, “we foresee being able to get that howitzer out to 70 km.”

The metallurgy of the new barrel should be robust enough to fire even more advanced munitions like hypersonic and ramjet rounds that enter service beyond 2023, Maranian said, although he doesn’t have a date yet. Experimentation will begin “within the next couple of years,” he said, but he thinks hypersonic cannon shells could reach out to 100 km (63 miles).At that range, Maranian said, cannon can take on targets that today require more expensive rockets. So what do the rockets do? Well, they get longer-ranged too. That means, in turn, that means rockets take over missions from the most expensive missiles, so those have to gain range as well.

The current precision rocket — the Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System, or GMLRS — fires about 70 km (44 miles). That’s roughly the same range as the upgraded ERCA cannon and shorter than hypersonics.

So the Army is working on GMLRS Extended Range that will roughly double that, Maranian said, to about 150 km.

Then there’s the artillery’s longest-range system, the Army Tactical Missile System. (This is a “semi-ballistic” missile, not a true ballistic missile). ATACMS in its current form can hit targets about 300 km (188 miles) away. For the last few years, the Army has been developing a replacement that’s both half the size — allowing two in a HIMARS launcher or four in an MLRS — and longer-ranged. Officially, the new missile could go right up to the INF treaty limit of 499 km, although if the treaty collapses expect that number to go higher.

The ATACMS replacement was originally called Long Range Precision Firepower. But when the Chief of Staff designated “Long Range Precision Firepower” as his No. 1 modernization priority, he had a much wider range of weapons in mind — namely, the whole portfolio of advanced artillery Maranian’s discussing. So the weapon formerly known as LRPF will soon be formally renamed PRSM, the Precision Strike Missile.

Lockheed Martin and Raytheon will test-fly their PRSM prototypes next year, in 2019. The winner’s weapon should achieve Initial Operational Capability in 2023 — and then get upgraded over time. The initial PRSM will only be able to hit stationary targets on land, but the Army is working on seekers that would let it track and kill moving targets on both land and sea, including enemy warships — a particularly useful capability for Army batteries on islands in the Pacific. Other warheads under study would home in on radio and radar signals or loiter over the battlefield like drones, collecting intelligence and beaming it back.In the longer run, Maranian said, the Army is looking at even more exotic technologies such as railguns — now being pioneered by the Navy — which use electromagnetism to launch projectiles at about Mach 7. And there are other projects moving along in parallel, like an automatic loader for the M109 Paladin howitzer to increase its rate of fire. Human loaders manage four rounds in the first minute, then one a minute thereafter as they tire, but the autoloader technology could offer 6-10 a minute as long as ammo is left.

All this investment in new technology is a marked contrast from the previous 20 years, when the artillery suffered two major program cancellations — the Crusader howitzer and then the howitzer variant of the Future Combat Systems. One of the Army’s most neglected branches is now the chief cornerstone of its approach to future war.