Re: Levant crisis - III

Posted: 24 Jul 2017 21:02

one of tiger forces temporary bases in the desert. the green city buses are ferrying people from bases in the west to the front

Consortium of Indian Defence Websites

https://forums.bharat-rakshak.com/

or they have read what happened to Gen. B...ev, the first Caliph of the Chechen rebels. In this case, fire gun at wrong time at wrong ppl - get missile by return trajectory.long string used to trigger it, the piece is in shaky state so taking no chances which direction it will fire - front or back.

As said often before,"it's (still) all about oil!"Secret Russian-Kurdish-Syrian military cooperation is happening in Syria’s eastern desert

In the first of a series from Syria, Robert Fisk says that new connections, however tenuous, demonstrate that all sides are determined to avoid military confrontation between Moscow and Washington

Robert Fisk Resafeh, eastern Syria @indyvoices 23 hours ago

A Syrian soldier in front of a sign on the main road from Homs, ‘welcoming’ visitors to the Isis ‘Caliphate-Province of Raqqa’ Nelofer Pazira

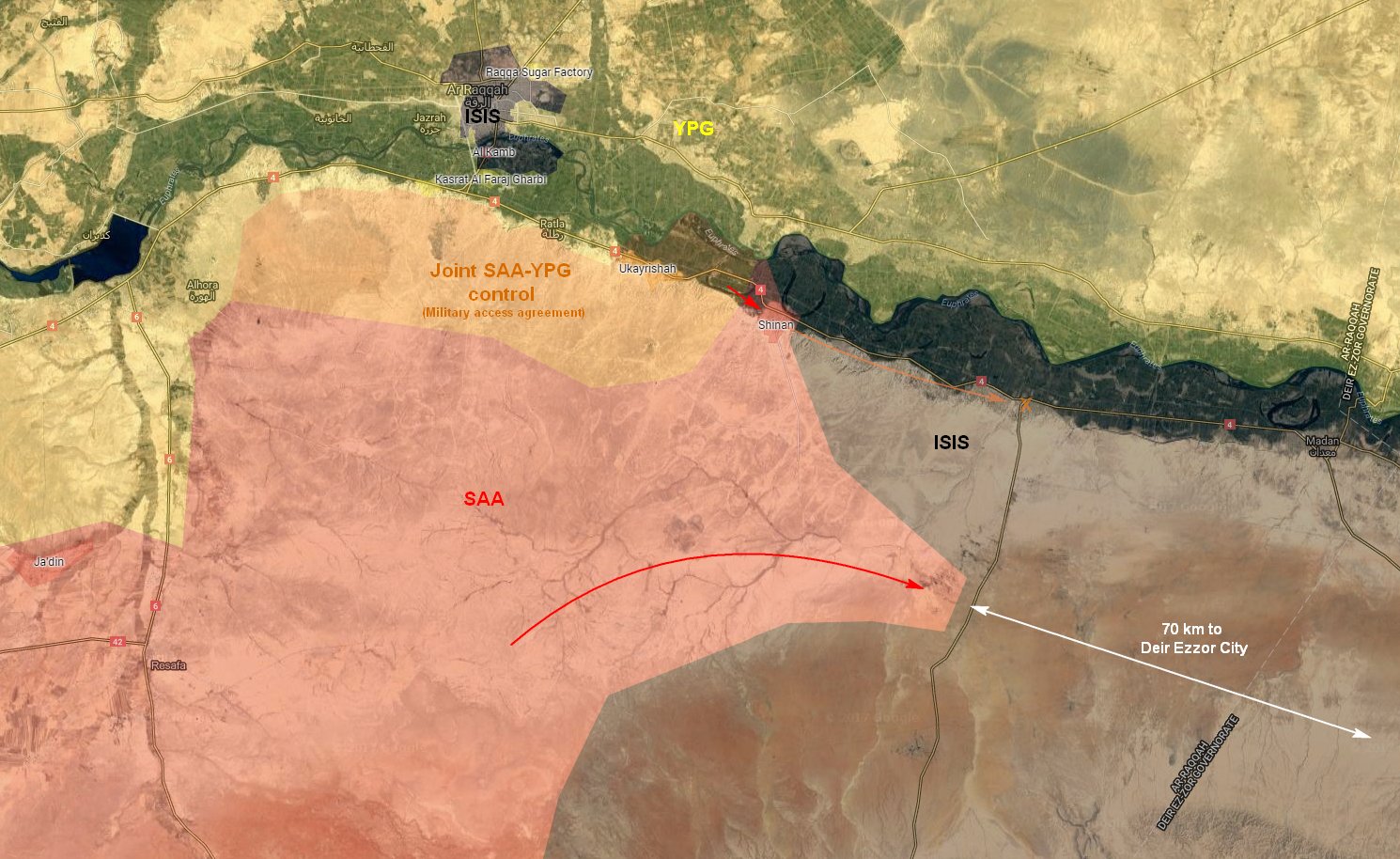

After a sweeping Syrian military advance to the edge of the besieged Isis “capital” of Raqqa, the Russians, the Syrian army and Kurds of the YPG militia – theoretically allied to the US – have set up a secret “coordination” centre in the desert of eastern Syria to prevent “mistakes” between the Russian-backed and American-supported forces now facing each other across the Euphrates river.

The proof could be found this week in a desert village of mud-walled huts and stifling heat – it was 48 degrees – where I sat on the floor of an ill-painted villa with a Russian air force colonel in camouflage uniform, a young officer of the Kurdish militia – with a YPG (Kurdish People’s Militia) patch on his sleeve – and a group of Syrian officers and local Syrian tribal militiamen.

Their presence showed clearly that despite belligerent Western – especially American – claims that Syrian forces are interfering with the “Allied” campaign against Isis, both sides are in reality going to enormous lengths to avoid confrontation. Russian Colonel Yevgeni, thin and close-shaven with a dark moustache, smiled politely but refused to talk to me – The Independent being the first western news media to visit the tiny village near Resafeh – but his young Kurdish opposite number, who asked me not to disclose his name, insisted that “all of us are fighting in one campaign against Daesh [Isis], and that is why we have this centre – and to avoid mistakes”. Colonel Yevgeni nodded approvingly at this description but maintained his silence – a wise man, I thought – for he must be the easternmost Russian officer in Syria, only a few miles from the Euphrates river.

The 24-year-old Kurdish YPG representative, a veteran of the Isis siege of Kobani on the Turkish border, said that just over two weeks ago – after the latest Syrian offensive took Isis forces west of Raqqa by surprise – a Russian air strike had mistakenly targeted a Kurdish position. “That is why we set up our centre here 10 days ago,” he said. “We talk everyday and we already have another centre at Afrin to coordinate the campaign. We have to make one force that fights together.” The presence of these men at this remote desert outpost shows just how seriously Moscow views the strategy of the Syrian war and the need to monitor the largely Kurdish “Syrian Democratic Forces” who are already inside Raqqa with the support of US air strikes.

The SDF – which has nothing democratic about it except perhaps its pay scales – is regarded with deep suspicion by the Turks, who will be enraged to learn of the Syrian-Kurdish cooperation, even though both Ankara and Damascus are both ferociously opposed to the creation of a future Kurdish state. But, however tenuous the new YPG-Russian-Syrian connections may be, they demonstrate that all sides are determined to avoid any military confrontation between Moscow and Washington.

There was more than a whiff of TE Lawrence about the self-confidence of these few men amid the dust and sand which covered most of us the moment we stepped outside their office. Around us on the desert floor lay hundreds of bombed or abandoned Isis oil “wells” – amateurishly built iron barrels and concrete platforms from which Isis extracted the oil to finance their caliphate, which once stretched from here all the way to Mosul. The YPG officer insisted that the location of the Russian-Syrian-Kurdish centre had no connection to the vast Syrian oil fields around us, but evidence of recent Russian and American attacks on the Isis constructions was everywhere.

Burned-out oil tankers, trucks and even some exploded Syrian tanks – presumably victims of Isis – lay across the desert. One trail of tankers – much like those angrily described by Vladimir Putin almost two years ago, taking oil exports to sell in Turkey – stood carbonised beside the road. Even a lorry carrying potatoes had been blitzed apart. There was no sign of bodies but the Syrian army had with some sense of irony left the original black and white Isis sign standing on the main road from Homs, “welcoming” visitors to the Isis “Caliphate-Province of Raqqa”.

Syria’s forward units of Russian-made tanks and infantry armour now cluster not far from the Roman and Umayad city of Resafeh, whose massive walls and stone towers still stand – untouched by Isis’s two years of culturecide, perhaps because their carvings display no human or animal images. Thousands of camels were being herded past the great and crumbling city of the ancient Calipha Umaya bin Hisham Abdul-Malik in a smog of dust which drifted over military hardware and soldiers alike. Resafeh was the Roman city of Sergiopolis, named after a Christian Roman centurion who was tortured and put to death for his religion – not unlike Isis’s own Christian victims in the deserts here three years ago.

The highway east from Homs was expected to have been the route of the Syrian attack this month. Hence the vast earth “berms” and defensive sand walls erected by Isis along the length of the road. But for Isis, the now-infamous Syrian army tactic of assaulting its enemies from the rear and flank drove the caliphate from hundreds of square miles of land west of the Euphrates.

General Saleh, the one-legged commander of the Syrian division on the Euphrates – who has adapted this policy many times, along with his fellow officer and friend, Colonel “Tiger” Suheil – says that his forces could, if he wished, be in the centre of Raqqa within five hours “if we decided to do that”. He described how his men had first driven al-Qaeda and Isis from the Sheikh Najjar industrial city outside Aleppo back to the Assad lake, how they had protected the water supply to the city at great loss to their own forces, how they had moved east from the Koyeress airbase to capture Deir Hafer and Meskane and other towns in the Aleppo countryside – and then suddenly surged south east, south of the Euphrates towards Raqqa.

“Our forces are now seven miles from the Euphrates between Raqqa and Deir ez-Zour, 14 miles from the centre of Raqqa and 10 miles from the old Thabqa airbase,” the general almost shouted. “How many Daesh did we kill? I don’t care. I am not interested. Daesh, Nusrah, al-Qaeda, they are all terrorists. Their deaths do not matter. It’s war.”

But, I suggested to General Saleh – because I had been studying my sand-blasted maps and had listened to many a military lecture in Damascus of late – surely his next target would be not Raqqa (already partly invested by American-backed forces) but the huge surrounded Syrian garrison city of Deir ez-Zour with its thousands of trapped civilians.

“Our President has said we will recover every square inch of Syria,” the general replied, repeating the mantra of all Syrian officers of the regime. “Why do you say Deir ez-Zour?” Because, I said, that would release the 10,000 Syrian soldiers in the city to fight on the war front. There was just a hint of a grin on the officer’s face, but then it faded. In fact, I don’t think the Syrians will get involved with the American-supported force fighting for Raqqa – that, after all, was the point of the little “coordination” centre I saw in the desert – but I do believe the Syrian army are heading for Deir ez-Zour. As for the general, of course, he was saying nothing about this. Nor, obviously, did he believe in body counts.

There is, in reality, another intriguing tactic being deployed by the Syrian administration. The local Rif Raqqa governor – “rif” indicates the countryside around a city, not to be confused with the town itself – is now setting up headquarters near General Saleh’s caravan. It’s a real campaign caravan, by the way, which rocks when you step aboard, his office and bedroom combined in one small room, his black walking stick by the bed-head. The local governor, however, is scarcely a mile away, planning the restoration of water and electricity supplies, the financing of public works and relief for refugees.

When I left the area, 29 families – cartloads of children and black-shrouded women and upturned sofas – had just arrived in Rasafeh from Deir ez-Zour to seek the Raqqa governor’s assistance. Another 50 had arrived the previous day. It seemed perfectly obvious that if the Syrian army lets America’s largely Kurdish friends occupy Raqqa, it is going to help the Syrian government civilian administration take over the city by the force of bureaucracy. How would that be for a bloodless victory?

But military self-confidence is often the handmaiden of misadventure. The highway that forms the tip of the Homs-Aleppo triangle has now been extended 60 miles to Resafeh, and General Saleh makes no secret that Isis and its fellow cultists return across the desert after dark to attack his soldiers. These men – many of whom are teenagers – are billeted in tent encampments beside the road, protected by tanks and anti-aircraft guns. And their battles are constant, Isis still placing IED bombs beside the highway today. When I later travelled across the desert to Homs, I followed for some time a truck carrying a 155mm artillery piece so overused that its barrel had split apart.

Yet already, Syrian engineers are restoring electricity capacity from the desert generating stations which have only recently been hideouts for Isis leaders, a power system intimately connected to the Syrian oil fields, slowly being recovered from the Isis enemy, which remain – modest though they are in comparison with the great Gulf, Iraqi and Iranian oil resources – Syria’s “pearl in the desert”. Who controls these wealth machines – how their product will be shared now it has been freed from the Isis mafia – will determine part of Syria’s future political history.

Democratic member of Congress from Hawaii, Tulsi Gabbard, who traveled to Syria and met Bashar al-Assad earlier this year, told FNC's Tucker Carlson on Monday night what she has learned about the origins of the war in Syria.

"This isn't a matter of giving weapons to people, but they end up falling into the wrong hands. We are directly arming militants who are working under the command of al-Qaeda, all in this effort to overthrow the Syrian government," Gabbard explained. "We have been providing direct and indirect support to al-Qaeda, the very group which attacked us on 9/11, that we are supposedly continuing to fight against and trying to defeat."

Al Qaeda was created in the 1980s through a CIA program which funnnelled money and weapons through Pakistani intel services to the Afghan mujahadeen called Operation Cyclone, in order to to combat Russian forces in Afghanistan.

"The thing that should make everyone feel sick is that people would rather support, directly and indirectly, al-Qaeda, than actually give up their regime change goals," Gabbard added.

Earlier this month, President Trump ended a CIA program shipping money, supplies, and weapons to rebel groups in the mideast in order to combat Russian forces in Iraq and Syria, according to the Washington Post.

TRANSCRIPT

REP. TULSI GABBARD: For the benefit of your viewers, let's talk about what this CIA program actually was. It has been widely reported that for years now, the CIA was provding arms, intelligence, money, and other types of support to these armed militants who were working hand in hand, and who are working hand in hand, and oftentimes under the command of al-Qaeda in Syria.

This isn't a matter of giving weapons to people, but they end up falling into the wrong hands. We are directly arming militants who are working under the command of al-Qaeda, all in this effort to overthrow the Syrian government.

TUCKER CARLSON: That is groteque. Why would anyone defend this?

GABBARD: It is this addiction to regime change. And this idea that somehow this is what must be done, without actually looking at the facts. We have been providing direct and indirect support to al-Qaeda, the very group which attacked us on 9/11, that we are supposedly continuing to fight against and trying to defeat.

The thing that should make everyone feel sick is that people would rather support, directly and indirectly, al-Qaeda, than actually give up their regime change goals.

View from abroad: Turkey’s increasing isolation

Irfan HusainUpdated July 24, 2017

AS Turkey’s President Erdogan extends his purge, thousands have been locked up and await trial for their alleged role in last year’s attempted coup. Ten of them are German citizens who face terrorism charges. In today’s Turkey, any suspected links to the Gulenist movement are equated with terrorism. Thus, schoolteachers, university professors, civil servants, judges and prosecutors — apart from tens of thousands of police and military personnel — have been suspended, sacked or jailed.

This state of affairs is being watched with growing disbelief and dismay by Turkey’s friends and allies around the world. The recent arrest of Peter Steudtner, a human rights activist, has triggered a wave of anger in Germany. The country’s finance minister warned travellers to Turkey that their safety could not be guaranteed. The foreign minister, Sigmar Gabriel, termed Steudtner’s arrest “absurd”, and went on to say: “German citizens are no longer safe from arbitrary arrests”.

Two mass circulation dailies have stopped ads promoting foreign investment that carried the slogan: “Come to Turkey. Discover your own story.” The government has warned that it is now reviewing its policy towards Turkey.

Considering that some three million German tourists visit Turkey every year, a significant decline in this number will seriously dent the economy at a time it is already reeling from the fallout of the Syrian civil war. The Turkish lira has halved in value over the last five years, and inflation is at 8pc while inflation has risen to 10.5pc. Germany has announced a review of requests for arms sales; in 2016, it exported nearly 84 million euros worth of military hardware to Turkey.

Erdogan has lashed back, saying such tactics would not force Turkey to change its views. He went on to demand why Germany was giving asylum to army officers accused of Gulenist sympathies, and allowing the Kurdish separatist outfit, the PKK, to operate freely on its soil.

This acrimony has been steadily building up in the aftermath of Erdogan’s growing hubris following his narrow and controversial victory in the referendum to practically grant himself dictatorial powers. As he has cracked down on his political opponents, he has permitted his own animosity against Germany to shape his government’s attitude towards its most important European ally. He was frustrated when the Germans refused to allow him to hold rallies in Germany to address the many Turks who live there, asking for their support in the referendum.

With the talks for admission to the European Union in the doldrums, Erdogan feels he has little to lose by lashing out against the Germans, despite the presence of three million Turks who work and live in Germany. The EU — and Germany in particular — depends on Turkey to block the westward journey of Syrian asylum-seekers. Nearly a million of these unfortunate refugees reached Germany until the EU reached an agreement with Turkey.

It is not Germany alone that has incurred Erdogan’s wrath: the United States, too, has been targeted by the Turkish president in his diatribes. When he visited Washington recently, he was accompanied by a contingent of armed guards. These plain-clothed agents beat up a number of protesters on camera, and the FBI has issued warrants for their arrest, even though they are now back in Turkey. Video clips played on American TV channels and downloaded from the internet caused outrage in the United States.

More importantly, Erdogan is furious with Washington for allowing Syrian Kurds to play a leading role in the battle to oust the militant Islamic State group from Raqqa. He fears that an emboldened YPG, or The People’s Protection Units, will seek an independent enclave close to the Turkish border. Turkey has long regarded the YPG to be an adjunct of its own separatist Kurdish group, the PKK, and has launched a vicious crackdown on Kurdish-majority areas in south- eastern Turkey.

And now Turkey has angered Saudi Arabia by its support of Qatar in its dispute with the kingdom and the United Arab Emirates. By sending in food supplies to the beleaguered state, and by posting troops at its small base, Turkey has broken ranks with the Sunni states bent on punishing Qatar for its independent policies. The fact that the crisis appears to have been triggered by the UAE hacking an official Qatari website seems to carry little weight with leaders who are determined to reveal their immaturity to the world.

So how isolated internationally is Turkey as a result of these aggressive words and moves? Currently it has drawn close to Russia whose leader, Vladimir Putin, views Turkey’s estrangement from Europe and America as a chink opening up in the Western alliance. Iran, too, is a major trading partner with $4 billion in goods exchanged annually.

The recent rally for the return to the rule of law that began with a march from Ankara to a massive demonstration in Istanbul shows that Erdogan is not the popular figure he would like to be. The margin of victory in the referendum, despite the massive state resources that boosted the ‘Yes’ campaign, was just around one per cent, and this too was contested by many observers.

Erdogan and his supporters have branded their opponents ‘traitors’, thereby deepening the polarisation that has taken root in the country.

The divide is between secular, educated and westernised urban Turks and conservatives who are highly nationalistic, and see Turkey as an exceptional state. For them, Erdogan is a symbol of Turkish rebirth and return to greatness. But the government’s recent decision to remove Darwinian evolution from school curricula shows the backward direction of Turkey’s current trajectory

As Syria's army – with Russia's help – advances through the desert, Isis propaganda comes across the radio waves

Two officers tell me a creepy story, which might – given the nature of the Isis mind – have some pathetic truth. Several suicide bombers, they say, were found with women’s underclothes in their pockets, for the virgins they would meet in paradise

Robert Fisk Jebel al-Satih, eastern Syria

Pointing to Deir ez-Zour: the desert front line in the east of the country Nelofer Pazira

This is the third instalment in Robert Fisk’s series from Syria

For 60 miles across the vast desert of eastern Syria, far beyond the trashed Roman ruins of Palmyra, the army of Syria is moving through the hot grey sands towards the besieged garrison city of Deir ez-Zour. For 60 miles, tanks and heavy artillery – and brand new Russian Army multiple missile launchers – line the narrow, melting highway through the oilfields, pale tents flourishing in the dry wadis of distant hills which belonged to Isis only a month ago, gun batteries thumping amid the sand dunes.

We’ve been through this before, of course: Syrian army advances that turned sour in northern Syria, the long siege of eastern Aleppo, Isis retreats that transformed themselves into new and savage suicide attacks out of the desert and into Palmyra. But the Russian army foot patrols in the wrecked modern city of Palmyra – I even saw Russian Army Chechen troops in the city, a vital Muslim component to Moscow’s military alliance with Damascus – suggest that this time the Syrian army has its enemies on the run.

So enormous is the landscape – harsh, lined with green desert grass and baked sand hills – and so intense is the 47-degree heat, that images do greater credit to this desert war than dry essays on the strategy of an army that plans to free 10,000 of its soldiers still holding out further east, surrounded by Isis for three years in the ancient city of Deir ez-Zour, along with 400,000 civilians in two pockets of land in the valley of the Euphrates.

Sixty miles beyond Palmyra I travelled eastwards, the only western journalist to reach this far front line in a convoy of Syrian vehicles until we stopped just five miles short of the crossroad town of al-Sukhnah.

“Sukhnah” means heat. It is the right name. Isis is still there. The desert mirages turn empty sand beds into waterless rivers, but the Syrian encampments and the 122- and 130mm guns are real enough. So are the tanks heading east: some loaded with infantry, thrashing up the tarmac, truckloads of green-painted ammunition boxes crammed on top, soldiers clinging to the tailboards.

The wreckage of war – a bombed-out Isis truck, a shattered army lorry, carbonised buses pushed off the road – is everywhere. A bearded Syrian officer – many of them have grown these big bushy Isis-style beards over the past two years, perhaps to mock their enemies – shouts that the gun line have been ordered to fire, and then the desert shakes ever so slightly and long lines of sand streak in front of the artillery.

They look like those big wheeled guns on the old silent Somme newsreels and they are almost as quiet in the desert. The fine dust absorbs the thumping detonations.

When we stop at a military post beside the highway, a sergeant emerges holding two tiny drones, just shot down at a height of 350 feet by a soldier with a Kalashnikov, the machine stinking of burned plastic. A beady camera glass hangs from one wire, the little rotors still rotating at the touch of a finger.

Isis, through the heat haze, is watching us through these sinister little lenses. Someone with a fully working brain in al-Suknah, ready to retreat no doubt, is looking for targets.

Only when we pass the batteries of Russian army BM-30 SMERTCH “Whirlwind” multiple rocket launchers, their Russian crews beside them, magenta and blue camouflage amid the sand, does a Syrian officer ask us not to take pictures. No problem with Syria’s weapons. We can shoot photographs of as many guns as we like, as many mortar batteries, although they appear dwarfed by the immensity of the landscape.

There’s an operational battle map in General Mohamed Khadour’s air-conditioned headquarters. It shows a black patch for al-Sukhnah, and just to the left a grim series of blood-red circles. These are the gun lines. And Khadour, the senior army commander for this huge area of desert and remote cities – tall, head shaped like a bullet, thinning hair, face darkened by the sun; a 58-year-old graduate of the Aleppo military college with an infantry training degree – coldly reads off a set of coordinates to open fire.

Beside him on a sofa leans a heavy black six-chamber 46mm rocket gun that his men captured up north in Hassakeh – “RPG-6, GLV-HEF [stock number] 4348” for those who can trace its foreign manufacturers – and the general looks contemptuously at it.

“However many weapons they got from the West, Isis is finished,” he says. “They are like a banana that has fallen out of its skin. Only the skin is left.”

Read more

Al-Qaeda claims it is ‘fighting alongside’ US-backed forces in Yemen

Isis and al-Qaeda are little more than glorified drug cartels

Isis will become ‘al-Qaeda on steroids’ after defeat, official warns

I’m not so sure about this. There’s a small truck park in Palmyra filled with the big black iron suicide trucks that Isis manufactured in its caliphate, identical to the massive killer cars captured by the Iraqi army in distant Mosul, far to to the east. General Khadour reports that in one month his soldiers have faced seven suicide trucks and 20 individual Isis suicide fighters, all of whom had blown themselves to pieces.

And I ask the same old question I put to everyone who fights Isis: who are they really? And I get the same reply from the general. “Animals,” he says. “But even animals are not evil.”

Curiously, the brain inside the Isis “animal” does not interest these soldiers. They regard the al-Nusrah / al-Qaeda fighters as far better trained – and with far more sophisticated Western weapons and anti-aircraft missiles – than Isis. For Nusrah, still fighting on in Idlib province, they have a curiosity rather than respect. But for Isis, they have contempt.

There is a creepy story which two officers tell me, which might – given the nature of the Isis mind – have some pathetic truth. Several suicide bombers, they say, were found with women’s underclothes in their pockets – for the virgins they would meet in paradise.

20170725-134625-1.jpg

Syrian artillery in the desert outside the Isis-held town of al-Sukhnah (Nelofer Pazira)

Some generals only speculate on dates – a sound precaution in the Syrian war – but General Khadour does not hesitate to tell me that he will reach and “liberate” Deir ez-Zour by the end of August, just 30 days away. Why not? He was head of the security and military headquarters in the eastern region of Syria – including the surrounded city – until he was flown north to fight Isis and Nusrah around Hassakeh. He will, no doubt, resume his duties there when his army breaks the siege.

“I and General Mohamed Sbeh here,” he says – Sbeh, Khadour’s subordinate officer, sits, rotund and narrow-eyed, listening like a fox to his left – “told the people of Deir ez-Zour we would come back for them, and we shall. That is what I am doing. We have got a third of the way. We have just 130 kilometres to reach Deir ez-Zour.”

An Isis radio station went on the air a few days ago and many of the soldiers heard it. “They said they were still winning and our soldiers in the desert heard it,” General Khadour said. “Isis said: ‘We have captured a major in the army and destroyed a tank of the regime and killed a lot of ‘pigs’ [soldiers].’ We all laughed. It was a lie. We have no one captured; we have not lost a tank. We are winning.”

But the Syrians are of course taking casualties. On a small hill captured only 24 hours earlier, General Sbeh told me he had two soldiers “martyred”, one of them an officer, and others wounded. But he said that Isis was now retreating to Mayadeen, along with some of their families.

These Syrian officers are dismissive of American power – their army has certainly advanced in the desert faster than the US-supported and largely Kurdish “Syrian Democratic Forces” east of the Euphrates when they approached Raqqa – and dismissively list the American airbases on Syrian soil.

“We know their bases are outside Hasakeh, and at Al-Ermeilan, Al-Shedadeh and Ein al-Arab [Kobani] and other places – but these are temporary,” Khadour says. “They cannot stay there.

The general says he will never retire – like many soldiers, I suspect he likes fighting too much – and he says he will never give up till the end of his life. We first met in Aleppo five years ago when he was defending the middle-class Saef al-Dawla district. “We did not know whom we were fighting then,” he says.

“They had no tactics and we had much to learn. Then they would start getting sophisticated equipment from the West and we had to adopt our tactics. Now we are fighting in the desert.”

And therein runs a tale. For the Syrian Army was trained – always – to fight Israel on the Golan Heights, to go to war in cooler climates, to head south. But now it is fighting its way east in arid lands that resemble those of the Iran-Iraq war – indeed, of the Second World War in Egypt and Libya – and it has become a desert army.

Khadour ponders this for some time and then looks across the destroyed modern metropolis of Palmyra. In Roman antiquity, Queen Zenobia ruled this ancient city, infuriating the empire with her arrogance and independence. No civilian has returned to Palmyra. The general gazes across the smashed hotels and villas and shops and laughs mirthlessly. “Why did Zenobia ever come here?” he asks

Idlib and Deir-Azzor are both striking for holding out in a sea of hostiles for so many years. Deir-Azzor even more so, as it's been so thoroughly cut off and far away from friendly lines for that entire time. The (failed) seige of Deir-Azzor ranks right up there in military history alongside Rorke's Drift, Tobruk, Stalingrad, Bastogne and Khe San.Singha wrote:russians have done this with a great economy of force and cost vs the usual khanish show

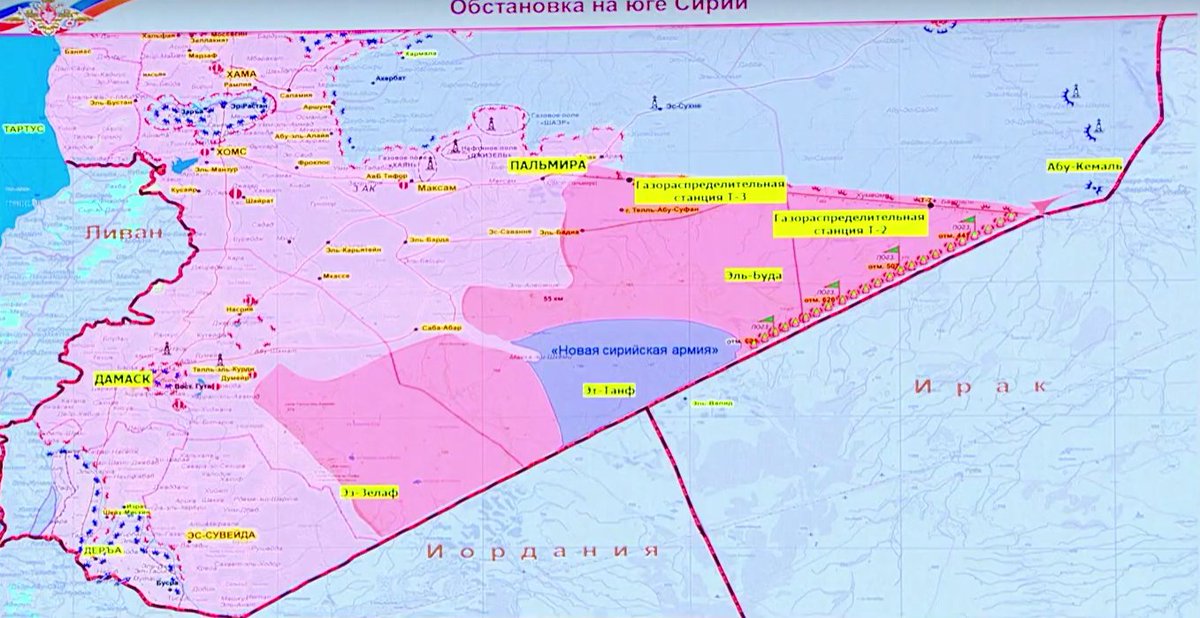

map just before the russian intervention in Sept 2015

map now