http://blogs.nature.com/news/thegreatbe ... shima.html

TEPCO sets out Fukushima crisis plan - April 18, 2011UPDATE: The Associated Press reports that the robots have detected peak radiation levels of around 50 millisieverts

per hour inside units 1 and 3 (World Nuclear News also has a nice summary of the range of numbers seen, and what they mean). The bottom line is that rates in some places at least are far too high for human workers to enter the plant. The readings point to a long and difficult clean up process. You can read more about what the numbers mean here.

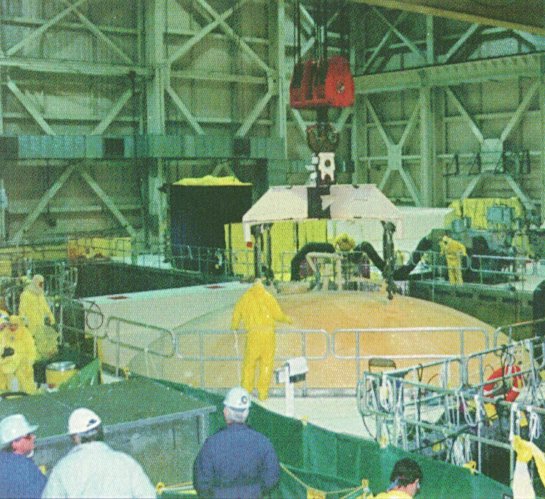

Over the weekend, remote-controlled robots entered the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. The robots took the first photos inside the units 1 and 3 reactors (right) and assessed radiation levels. The Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), which runs the plant, sent Packbots, from the American company iRobot.

Packbots are used for explosive ordinance disposal in Iraq and Afghanistan, but in the wake of the nuclear accident iRobot sent two to Fukushima, along with two larger Warrior bots. The robots are equipped with cameras and radiation detector equipment, and are even capable of opening doors (presuming they're not locked). Normally the robots are radio-controlled, but iRobot installed a fiber-optic link on the models at Fukushima, to make it easier to operate them in the harsh radiation environment that is believed to exist inside the plant.

Click here for more on the role of robots at Fukushima.

http://blogs.nature.com/news/thegreatbe ... lowch.html

Ever since a massive earthquake and tsunami struck the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant on 11 March, activities at the site have been hasty, improvised, and often uncoordinated. For engineers, project managers (and reporters who cover large projects), nothing has made the chaos more pronounced than the lack of a flowchart. Yesterday that all changed: the world now has a brightly coloured chart of the next six to nine months at Fukushima.

Flowcharts are omnipresent in the world of big projects. They impose order on the myriad little tasks needed to complete a spacecraft or particle accelerator. They ensure that the hundreds or thousands of people involved have a clear view of the goal, and where their own efforts fit in. They're often derided, but as a reporter, I find them invaluable.

For the first month, Fukushima had no public flowchart. Instead, workers seemed to be pursuing an ad hoc strategy of flooding reactors and pumping out contaminated water. That made sense in the short term, but bringing the reactors under control is a mammoth task that will require careful planning and coordination. A flowchart is long overdue.

The new plan from the owner of the plant, the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), reflects the complex task ahead. It can be roughly broken down into three parts:

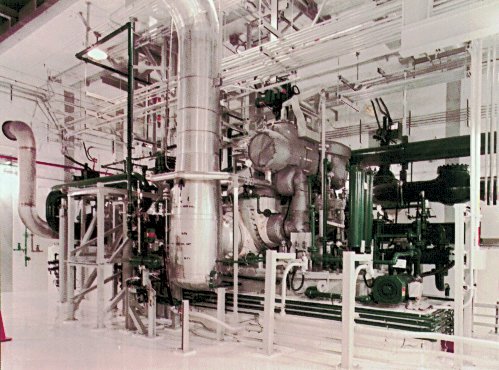

First, workers will continue to cool the reactors, whose nuclear fuel is still generating significant amounts of heat. In the near term, the cooling will be done as it is now, with water pumped in through the Emergency Core Cooling system. But in the long term, TEPCO would like to restore a "heat exchange function", which I take to mean they would like to have some system for re-circulating water through the core. This would avoid the massive build-up of contaminated water that has been a problem at the site for the past few weeks.

Second, but in parallel with the cooling effort, is a plan to deal with contamination on the site. The most pressing problem is the thousands of tons of radioactive water building up as a result of emergency cooling. Here, the utility seems to be taking a two-pronged approach. For lightly contaminated water the plan is to decontaminate it, possibly with zeolite filters of the sort we've discussed elsewhere. Higher level water will be stored in new tanks and other waste facilities at the site.

TEPCO is also planning to build a structure or structures over the reactors, which will keep radiation in, and hopefully keep rain and wind out. These structures will initially be flimsy, but the company plans to design more substantial concrete buildings to cover the reactors.

Finally, TEPCO is planning a coordinated monitoring system that will allow local residents to accurately gauge the risk they face as they begin to return to the evacuation zone.

The entire plan should, theoretically, be completed in six to nine months. It's an ambitious schedule, but if it were successful, it would bring a degree of stability to the residents of Fukushima prefecture.

It is very important to note that there is still quite a bit missing from the new plan. Most importantly, there is no mention of whether or how TEPCO might remove the roughly one thousand tonnes of nuclear fuel from the broken reactors before they are dismantled. This may be because radiation levels near the reactors are too high to contemplate further cleanup, or perhaps because the utility does not expect to be in charge of the next phase of the clean up.