Is Industrial Policy The Right Answer For India?

In the wake of the recently introduced Production Linked Incentives in various sectors, and the immense efforts being made to jump-start the semiconductor ecosystem, these questions take on some urgency. There are a number of factors, including the putative ‘demographic dividend’, and the fact that India is in the $2000+ GDP per capita range, which is often a takeoff stage.

Industrial Policy now has another driving force: national security, from at least two perspectives. The first is that India was for quite some time the world’s biggest buyer of defence equipment. It is a huge risk because of potential embargos. Second, it is clear that depending on others for crucial components can be potentially disastrous: remember US technology denials in supercomputing, and cryogenic engines, as well as China’s sudden decision to deny Japan rare earth supplies.

But there are some downsides too. India’s earlier flirtation with state-guided growth, as in the Five Year Plans, ended up in the debacles of the License-Permit Raj, large-scale nationalisation, and a ‘hybrid economy’ which was the worst of both worlds, capitalist and socialist. More recently, the ‘Make in India’ lion mascot has been quietly shelved, and despite Atmanirbhar Bharat, our trade deficit with China continues to soar.

The ghosts of the mai-baap sarkar and the ample mammaries of the welfare state continue to loom over India. Just a week ago, aspiring railway employees set fire to trains out of general frustration: it is reported that 1,25,00,000 people applied for 35,281 positions. The attractions are obvious: government jobs mean no accountability, no performance reviews, no chance of dismissal, plus baksheesh and pensions. This breeds mediocrity, as in the Soviet Union.

Is Manufacturing Important?

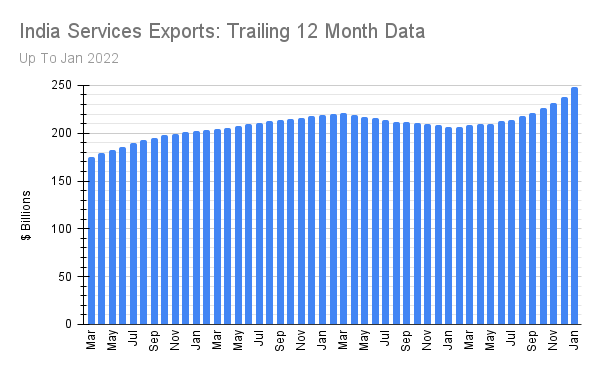

In a word, yes. Indians dazzled by the success of the IT services industry may not agree, and to give credit where it is due, it has provided decent jobs and created wealth (in many cases, extraordinary wealth) for a lot of individuals, but it is still a drop in the bucket.

According to Association for Computing Machinery, there is a total of four million direct and 12 million indirect jobs in IT, but that doesn’t begin to address the problem of providing jobs to the perhaps 10 million young people entering the workforce every year, often with a poor education that has taught them no skills.

Besides, manufacturing cannot be seen merely as a provider of jobs for the teeming masses: its effects persist. It may have a critical role in the creation of dynamic competencies that enable a nation to be resilient to changes in the industrial and trade environment. It is well-known that entire industries do have a lifecycle S-curve, wherein they rise, plateau, and despite possible mid-life kickers, they eventually decline. The physical and financial infrastructure, the supply chain linkages, and cluster effects, however, have lasting value: see how, for instance, Silicon Valley has weathered several waves of disruption and may yet recover from the latest.

In 2004, Dani Rodrik at Harvard wrote an influential paper titled Industrial Policy for the 21st Century. But these ideas are not new. In a seminal paper from 1986 in Research Policy titled Profiting from Technological Innovation: Implications for Integration, Collaboration, Licensing, and Public Policy, the Berkeley economist David Teece provided a grim warning against deprecating manufacturing:

… Put differently, the notion that the United States can adopt a “designer role” in international commerce, while letting independent firms in other countries such as Japan, Korea, Taiwan or Mexico do the manufacturing, is unlikely to be viable as a long-run strategy.

Teece was prophetic, as China has demonstrated by de-industrialising the US. This explains America’s huge and growing trade deficit with China, and the US is hanging on largely because of the fact that the US dollar is the world’s reserve currency. If and when that changes, the US economy will be in trouble.