https://open.substack.com/pub/sinocism/ ... dium=email

Forever Xi Jinping? Perhaps Not

He may put saving the regime from itself above vainglory, and even recovering Taiwan - Guest post by Chris Johnson

This a guest post from Chris Johnson, CEO of China Strategies Group and a former top China analyst at the CIA. Chris helps provide context for the recent round of PLA purges, and for what we may see at the now underway Fourth Plenum in terms of politics and personnel- Bill

With the world’s attention riveted on the on-again, off-again trade war between the United States and China, it can be easy to forget that Chinese President Xi Jinping, just like his American counterpart, Donald Trump, has domestic preoccupations that are far more front of mind for him than the ongoing trade spat. In fact, Xi this week is presiding over the Fourth Plenum of the 20th Central Committee, which will be an important milestone in this Central Committee’s political calendar. When the Politburo held its typical month end meeting in September, it announced the timing for the Plenum and said its agenda would be focused on approving the draft of the 15th Five-Year Plan, the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) strategic economic guidance blueprint for the period 2026-2030. Judging solely from the few teasers the government has released via central media, that document is sure to have profound implications for both China’s domestic development and for its trading relationships with the United States and many other countries.

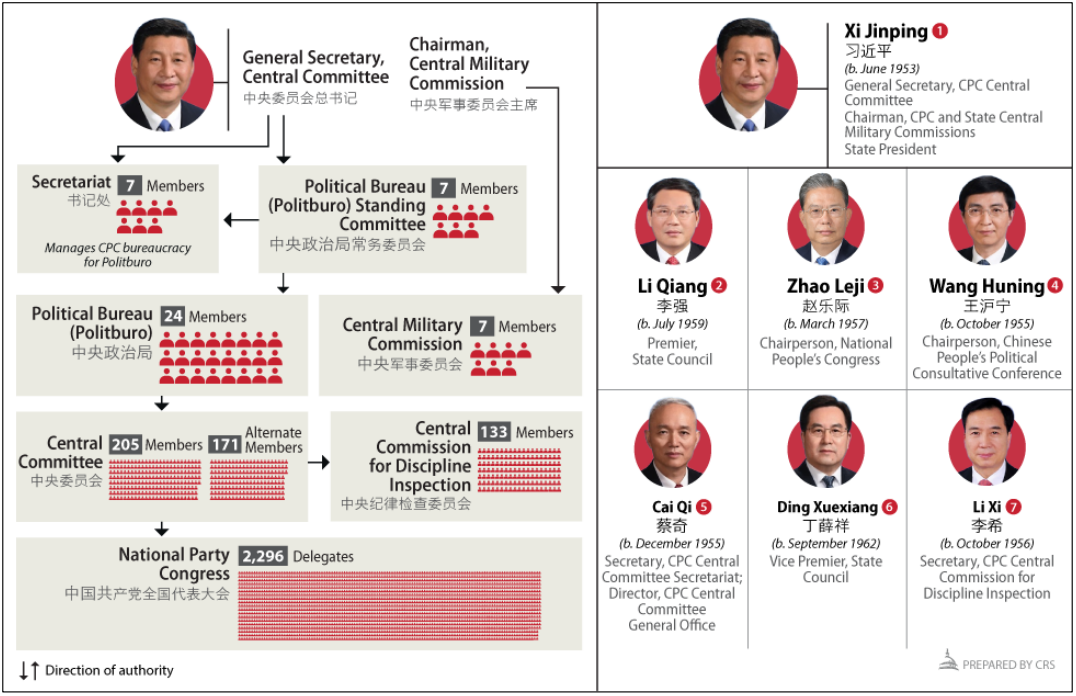

Lost in all that noise, however, is that plenums are, first and foremost, political affairs, and the Fourth Plenum is shaping up to be no different. At a minimum, the expanding purge of the high command of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), China’s military, seems primed to impact the conclave. The Chinese Defense Ministry’s announcement just days before the Plenum’s opening that nine senior PLA officers were expelled from the CCP and from the military makes that clear. Eight of those officers are members of the Central Committee, two of them are members of the CCP Central Military Commission (CMC)—China’s highest military policymaking body—and one of them is a member of the ruling Politburo. It is safe to assume that most, if not all, of those vacancies will be on the Plenum’s agenda.

Even on the civilian side of the Politburo ledger, there are issues to potentially resolve. The very unusual portfolio swap in April between members Li Ganjie and Shi Taifeng largely appears resolved, with both officials stabilizing in their new roles, but there is no doubt the move was odd. Similarly, their Politburo colleague, Ma Xingrui, abruptly departed as Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region CCP secretary in July. Official media said he would receive another post, but that has yet to materialize, at least publicly.

The Fourth Plenum may not deal further with those particular Politburo deck chairs, but it could take other actions. Given the relatively static elite politics of Xi Jinping’s now thirteen-year tenure, it is easy to forget that it was not always so. In fact, in the three decades that preceded Xi’s elevation to top leader, the Fourth Plenums of the 14th, 15th, and 16th Central Committees made important leadership changes to either the Politburo and its Secretariat or to the CMC.

Moreover, in two cases, fifth plenums witnessed significant changes to top CCP bodies that have strong parallels to today’s leadership configuration. At the Fifth Plenum of the 14th Central Committee in 1995, for example, the CMC was adjusted to add two new uniformed vice chairmen given the two incumbent vice chairs already were very advanced in age by that point and therefore would obviously retire at the next party congress. The same could be said now for CMC Vice Chairman (CMCVC) Zhang Youxia, who arguably already was extended beyond his expiration date at the 20th Party Congress and who will be 77 by the convening of the next one. The downfall of Zhang’s fellow CMCVC and Politburo member He Weidong, who himself would potentially have been due to age out in 2027, makes the need to signal Zhang’s successor even more urgent. And, we must not forget that Xi’s own ascension to CMCVC occurred at the Fifth Plenum of the 17th Central Committee.

That walk down memory lane is intriguing in a more big picture sense, too. As in those earlier periods, we have reached just beyond the halfway point in the 20th Central Committee’s lifespan. As such, the minds of CCP elites, as well as the regime’s foreign observers, are beginning to fixate on the 21st Party Congress in 2027 and its attendant reshuffling of the top leadership. That, of course, raises the question of whether Xi Jinping will embark on a fourth term then and, if he does, whether he will start to give some indication of his plans for the succession.

The conventional wisdom says Xi will rule for life. His chitchat with Russian President Vladimir Putin on a hot mic at last month’s military parade in Beijing calling septuagenarians like them children and referencing living to 150 obviously did little to challenge that conviction. And yet, there is a certain schizophrenia in the commentariat’s discussion of Xi and the succession. For example, his silence on a handover strategy was declared a looming crisis back in 2021, but China watchers still axiomatically claim he wants another term in 2027 with no transition plan in mind.

Unless Xi is a pure narcissist, however, that level of alarm seems unmerited. Like his overegged “bromance” with Putin, it partly derives from foreign hyperbole about Xi as another Mao or Stalin, two proper megalomaniacs. Analysts frequently suggest he is mirroring their smothering personality cults and capricious purges, making dying in office a next logical homage. Never mind that Xi follows smooth policy lines while theirs veered sharply. He is calculating where they were whimsical. His leadership philosophy was forged by tumult and disgrace when theirs took shape in triumph—and the list of dissimilarities goes on and on.

The “forever Xi” crowd also claims he ditched the practice of fixed decadelong tenures for the top leader out of personal ambition, but he—and initially the CCP barons who gave him power—instead viewed it as a regime-threatening crisis. The previous succession playbook offered certain benefits like a modest level of predictability and a false veneer of institutionalization. For Xi, though, the cost in Leninist accounting was too high. Without a strongman at the top to discipline it, the Party’s cohesion dissolved in the acid of rampant corruption. Worse, the regime’s hard power stalwarts, the military and security services, were borderline independent kingdoms jealous of their power and of uncertain reliability in a crisis. In short, what took twenty years to metastasize could not disappear in ten, as Xi’s expanding purges of his high command show.

Against that backdrop, the latest convulsions atop the PLA are of the utmost import. It is an iron law of CCP politics that a leader cannot make it to—to say nothing of staying—top leader without demonstrating an ability to at least work with, and preferably to control, that institution. It therefore is a critical player in any succession drama, as it demonstrated very clearly after Mao’s death with the arrest of his Cultural Revolution henchmen, the Gang of Four, and, in a subtler way, following the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown.

Some of the analysis of the current cycle of purges, which started in roughly mid-2023, says the ongoing chaos is an indicator of Xi’s lack of control over his generals. Other observers claim this is an intramural contest amongst rival senior officer factions behind the high walls of the PLA, casting Xi as merely a passive observer. In this framing, the PLA remains a mostly hermetically sealed kingdom where Xi, just like his immediate predecessors, gains access through careful bargaining and dolling out steady funding for the military’s parochial goals and the continued buildout of China’s already demonstrably lethal military capabilities. According to this view, the broadening of the purge shows Xi’s reputation as the most powerful leader of the PLA, and therefore of China, since Deng Xiaoping—and perhaps even Mao—is unwarranted. It is no surprise, then, that this camp judges Xi must remain in power for the long haul to continue his tectonic struggle with the mighty high command.

But this approach fails to give Xi the credit he is due. The civil-military dynamic it describes was accurate before he arrived, with the PLA occupying an expansive gray zone where it traded on its monopolies on certain forms of intelligence and military expertise to advance its perquisites. Xi disrupted that high command comfort zone early on with his “shock and awe” campaign combining a withering anticorruption drive with a comprehensive reordering of the PLA’s command structure. In both those spaces, Xi’s two immediate predecessors made fleeting efforts but failed to move the dial. Of course, Xi is fallible. He can get surprised, as seemed to be the case with the PLA spy balloon that drifted into mainland US airspace in 2023, but he has put the military in a much tighter box than it was in before he arrived.

In addition, even the supposedly formidable Deng struggled mightily to rally his fellow revolutionary-credentialed generals to undertake the Tiananmen crackdown and, in its aftermath, tried and failed to push through force restructuring. In his subsequent high command purge at the 14th Party Congress in 1992, he granted one of its victims a Politburo seat, if a hollow one, as a consolation prize to keep the peace within the elite. Xi may benefit from contending with a thinner political gene pool of senior officers, but He Weidong’s expulsion from the CCP makes clear he is doing no such favors. His removal of half the sitting CMC and the first active CMCVC since 1967 likewise is a display of raw power impossible to ignore and which catapults him beyond Deng.

Similarly, the idea that the ongoing purge—and even further tweaks to the force restructuring—are signs of Xi’s weak grip on the military do not hold water. Rome was not built in a day, and Xi is contending with monumental challenges that would vex even the most adept political operator. As noted above, the PLA also was not the only regime power player Xi deemed out of control when he arrived as party boss. The civilian security and intelligence services were their own corruption morass that required tending, probably prompting Xi, at least publicly, to pause his PLA reckoning for a few years while he brought that important constituency more under his personal control.

Moreover, the notion of rival senior PLA clans purging each other willy nilly while Xi looks on is equally wanting. If we acknowledge the PLA is no longer the freewheeling enterprise it was before Xi showed up, the old framework of searching for large networks under a single or a few leaders also should be revisited. In the case of the nine latest purge victims, for example, some of them have career ties to the PLA’s old 31st Group Army, which was rebranded the 73rd Group Army in Xi’s restructuring. He Weidong and his ousted colleague, former CMC member Miao Hua, also hail from the 31st Group Army, so the presumption is they were conspiring with each other and with those other officers in a larger cabal. But, at least so far, there is no public evidence linking the cases of He and Miao, nor can we be sure the clean out of officers who share career ties with them is anything more than, to borrow the Chinese aphorism, “cutting the grass and eliminating the roots” (斩草除根).

In that sense, Xi’s clear preference for maintaining an aura of infallibility, indefatigability, and unflappability makes the task of uncovering the truth all the more daunting. It seems unlikely, for example, that he would ever roll out a fulsome explanation of the purge in the almost theatrical style of Mao, with a catchy moniker like “the Lin Biao Antiparty Clique.” What we clearly can see is that Xi has spent much of his time in power railing against the formation of factions in the Party and the PLA. His actions have matched his words in breaking up powerful constituencies in the civilian leadership, so there is little reason to doubt he has worked hard to repeat that approach within the top ranks of the PLA.

Consequently, if the latest purge is really an indication of senior officers running amok, and not of Xi’s own doing, he is in a very weak position. The generals can be either untouchable, chastened, or, most likely, somewhere in between, but they cannot be—and are not—everything, everywhere, all at once. In short, the old solders are gone, and Xi, in his patient and methodical style, is proving very capable of managing their descendants. And, if Xi is contemplating a glide path toward stepping back, what better way to forestall any murmurings of weakness than by taking down a wide swath of the kingmaking PLA’s high command.

The same analyses of the military purges have drawn through lines to Xi’s confidence in his commanders to fight wars, most notably against Taiwan (and, presumably, the United States). In fact, informed observers frequently say Xi must stay in office to pursue his legacy obsession of reunifying with the island. Their main evidence is that he would start his fourth term the same year, 2027, he has mandated that the PLA be at least notionally up to the task. With a military wracked by corruption and of unproven combat effectiveness, however, Xi knows he might be gambling the regime with a Taiwan assault. Moving aside at some point to engineer a new and improved smooth handover may therefore seem a less risky way to earn his legacy chops.

There also is plenty of evidence Xi dwells on other preoccupations as much, if not more, than Taiwan. In that vein, handwringing about the succession confuses Xi’s caginess on the matter with a refusal to even contemplate it. But his public ideological oeuvre and private preoccupations suggest otherwise. Fancying himself a man of history, Xi fixates on the philosophically weighty matters “great men” do. With the party celebrating its centenary, and Xi readying for his norm-smashing third term, he was poised for such deep reflections in 2021.

Right on cue, central media announced Xi’s new remedy to the dynastic rise and fall that plagued China’s emperors for centuries. Xi’s answer, “self-revolution,” says the regime can autocorrect. A keen student of CCP history, he knows its succession track record desperately needs such a volte face. It is entirely conceivable, then, that his personal “self-revolution” checklist might include crafting a succession plan before circumstances—whether personal, internal, or external—force his hand.

Indeed, Xi’s fretting about China’s dynastic cycle mirrors his other nightmare scenario—repeating the implosion of the USSR. Chinese Communist thinkers long believed socialist polities were immune from the cycle given they had transcended its feudal dynasties and peasant uprisings. The failure of the Soviet experiment was a stark reminder that was not so.

Moreover, Xi privately has sermonized about the Soviet meltdown. Just after taking power, he told party insiders no one was “man enough” to stop Mikhail Gorbachev from disbanding the regime. But the bigger question is how such a “traitor” rose to the top to begin with. The answer, in part, is the Soviet leadership’s bungling of the succession. Instead of a rolling intergenerational handover, the Politburo wasted time handing the baton from one infirm septuagenarian to the next until desperation forced a fateful choice. Xi’s infatuation with the Soviet downfall presumably leaves him determined to avoid their mistake.

And yet, one must acknowledge that, even at senior levels of the leadership, Xi has shown signs of mimicking that failure. Zhang Youxia is not the only Politburo member Xi retained beyond the notional retirement age at the last party congress. Top diplomat Wang Yi stayed on too, and Xi kept yet another—though former—Politburo member, Chen Xi, in charge of the CCP’s top grooming ground for party cadre, the Central Party School. The latter retention is even more striking given that post used to be handed to the heir apparent under the previous loose succession protocol.

Similarly, Xi has loaded up his most trusted associates with numerous titles which previously would have been more dispersed. His principal lieutenant, Cai Qi, is the best example, serving simultaneously on the Politburo’s seven-man Standing Committee, chief secretary of that body’s executive arm, the Secretariat, and director of the CCP General Office, the Party’s day-to-day never center. Although those trends are not encouraging, it still is possible Xi could craft a novel solution that might better balance the internal tensions for him between staving off the dynastic curse for at least a bit longer and sticking with personnel comfort food.

In the end, of course, we are left to guess what Xi will do. The black box of Chinese elite politics is even more opaque under him. One thing is certain, however; searching for obsolete succession cueing is a dead end. In the old pattern, for example, the designated heir served as the sitting leader’s apprentice for five years. But Xi spent that time watching his feckless predecessor fiddle while the party burned, invalidating the practice for him. Demolishing such patterns then became his political signature as paramount leader, so his handover approach surely will follow suit.

In fact, Xi’s latest disruptive maneuver may offer a clue to his succession strategy. The Central Committee, as the CCP’s nominal top decisionmaking body, holds seven plenums during one of its typical five-year lifespans. For unknown reasons, Xi withheld this round’s third session until last year. That leaves the Fourth Plenum occurring when a usual cycle would be convening its fifth. This time, therefore, he could combine the agendas of the standard fourth (party affairs and ideology) and fifth (adopting the new five-year plan) meetings into one “super plenum.” Failing that, he could retain a “spare plenum” to deploy anytime between now and 2027, as the CCP Constitution mandates the Central Committee meet at least annually but sets no other firm constraints. That gives Xi a fair amount of flexibility to decide when, if it at all, he wants to show his cards on the succession. The point is that Xi frequently is more creative—and might even prove more magnanimous—than his foreign students often give him credit for. [/quote]